How The US Navy Used WWI Ghost Ships To Practice Bombing

When World War I ended in 1918, the United States entered a relatively long period of peacetime — this period lasted until 1939. However, the U.S. didn't enter full active combat operations in World War II until the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. From that point forward, the U.S. went on full-scale military operations and defense support, ensuring everyone who could support the war effort did so in whatever way possible.

Combat aviation improved throughout and after WWI, and in the decades of peacetime that followed, the U.S. trained heroes that would develop burgeoning aviation and radio technology. Since bombardiers required extensive training to ensure they could properly aim at and hit their targets, new methods arose to provide targeting support. This wasn't a significant concern for the U.S. Navy, which implemented training for emerging technologies as soon as the Great War ended.

Instead of bombing targets on the ground, which they did throughout the conflict, a lot of training went into hitting targets on the water. While the U.S. could have accomplished this with any number of dummy boats and rafts, that's not how things turned out. Instead, the Navy outfitted a number of WWI warships with various automation technologies for remote operation, allowing bombers to practice bombing live targets in the form of ghost ships.

A repurposed battleship got a new life

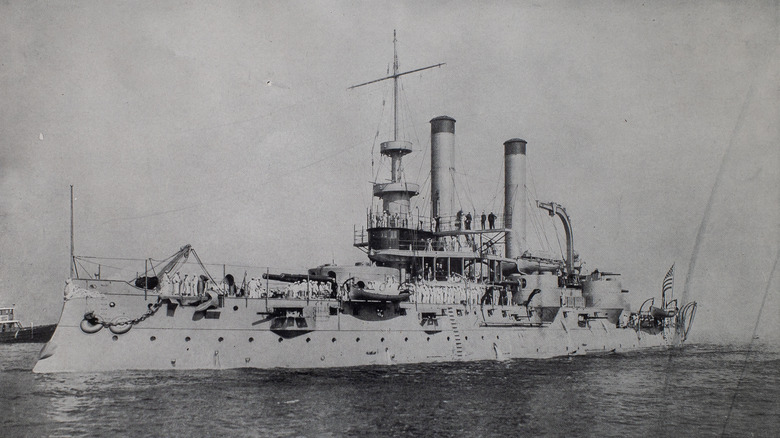

The U.S. Navy decommissioned the USS Iowa (BB-4) when WWI ended, but instead of setting it up as a museum or scuttling it to create an artificial reef, the U.S. Navy gave it a second life. The vessel was outfitted with remote-control radio equipment, enabling its operation without requiring anyone on board. In October 1920, the Navy rechristened the Iowa as Coast Battleship No. 4; its guns were removed, numerous compartments were sealed, automatic bilge pumps were installed, and its boilers were outfitted to burn oil.

The installed upgrades made remote operation possible, so an officer aboard the USS Ohio (BB-12), which served as a control ship, drove the remote vessel. Remote operations were limited, but the controller could steer the ship to starboard or port and place it on a steady course in one direction. This initial training operation kicked off on June 29, 1921, and personnel utilized numerous surface vessels and aircraft (including blimps) to seek out and find Coast Battleship No. 4 with the goal of striking the vessel.

Sinking the ship wasn't an option, as the bombs dropped by Navy and Marine Corps aircraft were 100 lb. sand-filled practice bombs and ten 500 lb bombs. After the exercise, the vessel was redesignated IX-6 and used as an experimental radio-controlled vessel. The initial test was successful, but not because most bombs missed their targets — it was useful in providing real experience for aviators hoping to strike moving vessels on the water. Of the 85+ bombs dropped, only two hit the ship.

One test led to many

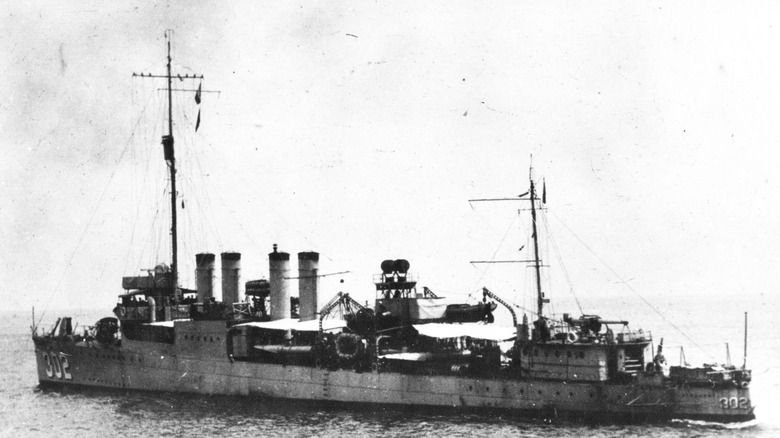

The success of the first radio-controlled test ship led to many others and the establishment of a practice that remained in use for several years. The Navy outfitted a variety of WWI vessels in this endeavor, which continued well into the 1930s. The USS Stoddert (DD-302) became Light Target Number 1 (IX-35), which was faster and more maneuverable than the Iowa.

This added a new element to training exercises because the IX-35's speed enabled dive bombers to make bombing runs using that practice. The former powerful Navy destroyer was difficult for bombers to hit due to the vessel's small size and speed of 30 knots. Sadly, the test resulted in a casualty, as one bomber, Lieutenant Thomas G. Fisher, died while attempting to drop a practice bomb when an accidental inflation of his biplane's flotation gear resulted in the shearing off of a wing.

The accident was an outlier, so the Navy continued using radio-controlled re-commissioned WWI vessels for target practice. This made it possible for aviators to practice all forms of bomb dispersals, including dive bombing and horizontal bombing. The tests helped improve training methods employed by the Navy and Marines, and they would come in handy throughout the naval conflicts of World War II.

A day that will live in infamy

By the time the Navy halted training operations with radio-controlled ships, two decommissioned battleships and multiple destroyers served as target vessels. The USS Mississippi (BB-41) sunk the Iowa during a Fleet Problem exercise off the coast of Panama in 1923. As she sank beneath the waves, the battleship USS Maryland (BB-46) fired a 21-gun salute, paying tribute to the Iowa's decades of service to the U.S. Navy.

Its demise came five years after her initial decommissioning, so it's fair to say she served the Navy long after her intended service was meant to end. The Iowa and other vessels helped prepare naval aviators for WWII, which began with a ferocious fury that pushed America into the conflict. After the attack on Pearl Harbor, the training provided by radio-controlled ships helped aviators target and strike moving Japanese vessels on the water, and it didn't take long for naval aviators to put their training to the test in intense battle conditions.

During the infamous Battle of Midway, which endured from June 3-6, 1942, U.S. aircraft sank four Japanese aircraft carriers and a heavy cruiser. The Akagi, Hiryu, Kaga, Soryu, and Mikuma all met their ends via U.S. dropped ordinance, which may not have been possible had the U.S. not trained for decades in the targeting and bombing of moving surface vessels.