Wearable Sensor Helps ALS Patients Who Can't Speak To Communicate

Researchers at MIT have created a new wearable sensor for people who have amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, better known as ALS. Many people with the disease gradually lose their ability to control their muscles, often losing their ability to speak. MIT researchers have designed a stretchable, skin-like device that can be attached to the patient's face and can measure small movements like a twitch or smile.

Using such a sensor, patients would be able to communicate a variety of sentiments, including "I love you" or "I'm hungry." They can convey sentiments such as those with small movements measured and interpreted by the device. MIT's sensor is thin and can be hidden with makeup to match any skin tone making it discreet.

Researcher Canan Dagdeviren says that the sensor is malleable, soft, disposable, lightweight, and virtually invisible. Camouflaging it with makeup would prevent most people from seeing it. The sensor was tested with two ALS patients, one male, and one female, and showed it could accurately distinguish three different facial expressions.

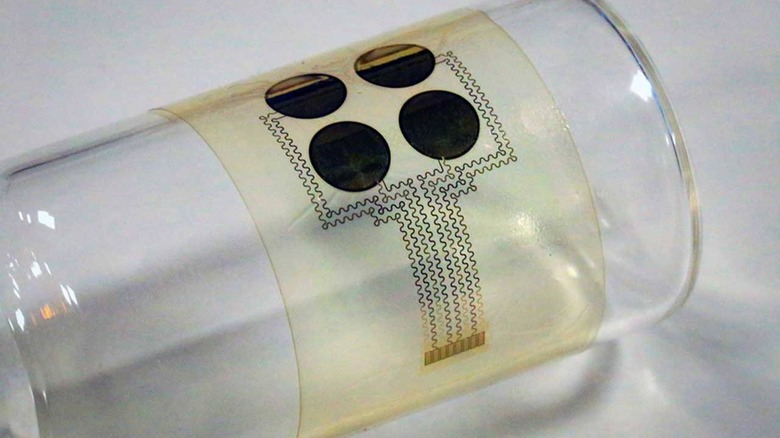

Distinguishable expressions include a smile, open-mouth, and pursed lips. One goal of the researchers was to create equipment, making it easier for ALS patients to communicate without requiring bulky equipment. Their sensor uses a quartet of piezoelectric sensors embedded inside a thin silicone film. Each sensor is made of aluminum nitride and can detect mechanical deformation of the skin and convert it into an electrical voltage that can be measured.

The components used in the sensor are easily mass-produced, and the cost is estimated at around $10 per device. Researchers had subjects perform various facial motions and created strain maps of each part of the face. The strain maps helped researchers determine where they could find the correct strain level to place their device on the face. In testing with the two ALS patients, they achieved 75 percent accuracy in distinguishing between the different movements. Accuracy with healthy subjects was 87 percent.