Volvo's Road-Plane Vision Is Beguilingly Disruptive

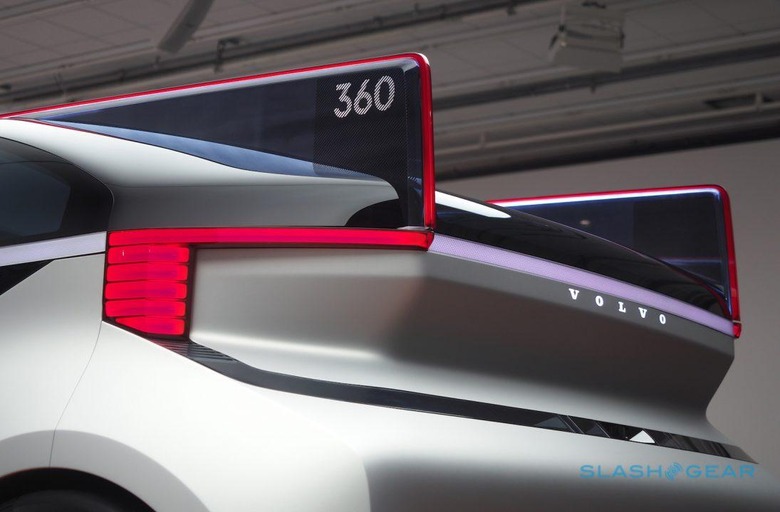

Air travel is dire, autonomous car development is split into poorly-communicating silos, and the goal of cutting road fatalities and making better use of infrastructure simply isn't the priority it ought to be. That, at least, is how Volvo sees the state of play in the self-driving world, and while the striking new 360c concept car may be a very visible expression of its focus on autonomy, arguably it's its ambitions for co-development and exploring new businesses that are more dramatic.

As a result, while the Swedish automaker may have a reputation for focusing on safety above all else, it's keen to add "innovator" to that legacy, too. Speaking in Gothenburg, Sweden, at the unveiling of the 360c, Volvo's top execs gave an unflinching assessment of the state of transportation in general and autonomy specifically. Unexpectedly, though, that started up in the air, not on the ground.

Turns out, Mårten Levenstam, senior vice president of product strategy and business ownership at Volvo, really hates air travel. So much so, in fact, that he's contemplating a whole new business opportunity for Volvo: disrupting short haul flights.

"Typically for me it's one hour to get to the airport, then one lousy hour at the airport getting through security," Levenstam explains of his frustration. "Then maybe another hour's flight, if it's a short haul. And then one more hour home again."

That's four hours in total; a period of time, Levenstam argues, within which you could probably drive the same distance. "From a consumer point of view it makes perfect sense to get rid of short haul flights," he suggests, "because it's a poor experience."

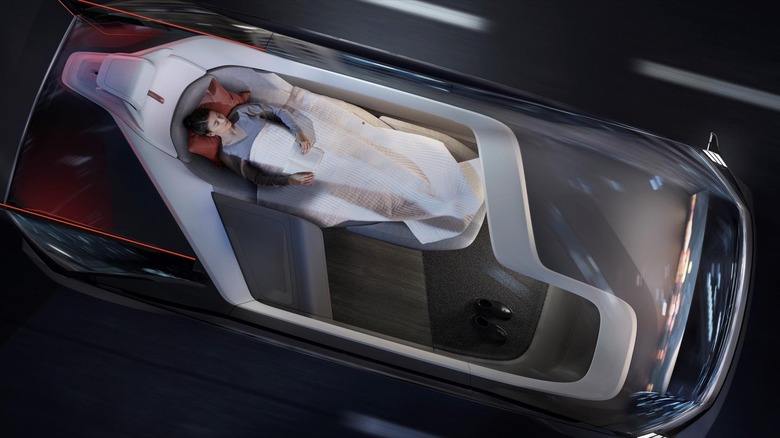

Currently, the downside to that idea is that your four hour road trip would require manually driving the car. Even with modern features like adaptive cruise control and steering assistance, that's a far more hands-on experience than sitting back in your airplane seat and munching a bag of mini pretzels as you're flown from A to B. That's where autonomous vehicles come in.

"We have never been in a place where we can do more things compared to now," Levenstam suggests, pointing to the rapid convergence of electrification, autonomous driving, and connected vehicles. The real problem, he says, is on the human side. City planners aren't thinking ahead to a self-driving ecosystem; those in charge of infrastructure aren't giving sufficient thought to things like dedicated autobahns for high-speed driverless EVs, which could be delivered power through the road as they whip between hubs.

That's before you get to the confusing and fragmented regulatory environment. "I think everybody now is stuck in their corner," Levenstam says, "including politicians." The current fears around just how safe autonomous vehicles are – and how safe they can be – before they're deployed at scale is a distraction, he argues.

"I think we're framing that in the wrong direction," he counters. "Right now, you're calling the NHTSA to get these vehicles approved. I think you should call the Food and Drug Administration."

As he sees it, autonomous car regulations should operate much in the same way that new drugs are approved. When pharmaceutical companies launch a new medication, it goes through technical trials before getting the green-light for broader use. So, too, would driverless vehicles.

"I think that's a good way to think of autonomous cars," Levenstam says. "It's not a good way to say 'deploy them when they are safe' – that's naive."

For Volvo particularly, Levenstam sees this as a potential new business opportunity. Just as Airbus and Boeing supply planes to the airlines, so the automaker could supply self-driving vehicles that would be used as "road planes." Each would, in effect, be a luxury pod that would navigate between locations, replacing short-haul flights – and the need to physically go to an airport first – while the passenger was cosseted inside.

All the same, there are legitimate questions around just how practical Volvo's ideas might be in reality. For a start, it's unclear just how many air travelers are potential "road plane" clientele. Even with the lower upfront and operating costs of an EV versus an aircraft, it's unlikely that taking a sleeper 360c from New York to Washington DC would be a low-cost option.

That could mean a few former occupants of the first class cabin moving into a driverless car, but whether it would have an impact on the number of people who typically travel in coach is questionable. Even if it did, the increase in traffic on road infrastructure would be significant. One of the reasons short-haul flights still make sense for airlines is economy of scale: 100 or more people in the same vehicle in the air, rather than 100 people each in their own, autonomous craft on the ground.

Levenstam is upfront that his vision is more than just about Volvo positioning itself as the auto industry evolves. "My point is not really that this will happen – I think it will," he says, "but really to talk about other changes we think will happen." It needs buy-in at every step, from passengers through to those responsible for the logistics of transportation, to regulators and planners.

No one company can make that journey alone. Volvo, though, is keen to be instrumental in how it's navigated. While the 360c may be a concept, and a non-functional one at that, the automaker is simultaneously pushing ahead with its working autonomous platforms.

Currently it supplies test cars to Uber, for instance, based on the XC90 SUV. The ride-sharing firm then adds its own autonomous hardware and software. Volvo's upcoming SPA2, however, the next-generation architecture which will underpin future vehicles, is built from scratch to be ready for autonomous driving.

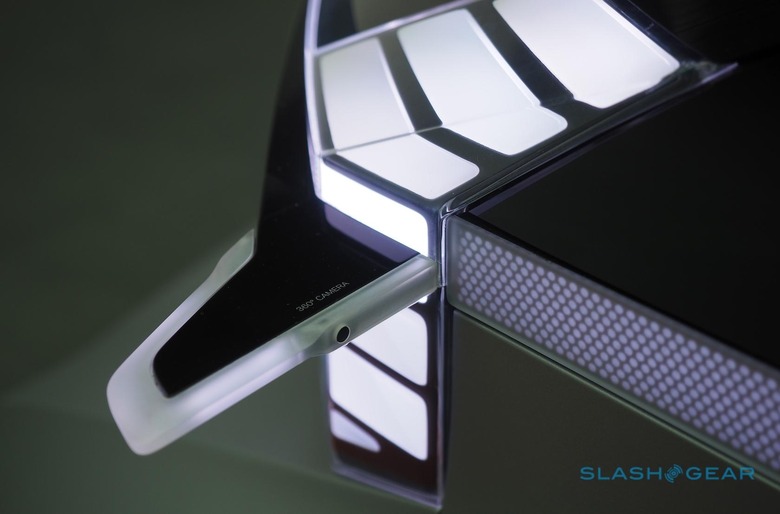

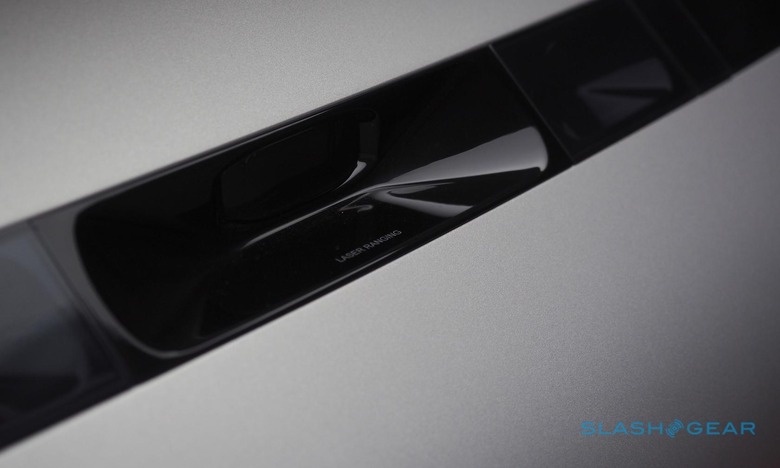

That means built-in redundancy for key systems, along with space for sensors and compute power from partners like NVIDIA. "We are working very completely with engineering on this car," Henrik Green, senior vice president of product and quality, says. Volvo envisages a modular business model, where partners could choose to use Volvo's entire stack – including autonomous software from Zenuity, the joint-venture Volvo began in early 2017 with safety tech firm Autoliv – or could mix and match, depending on if they wanted to supply their own sensor suite, their own software, or indeed both.

The SPA2 autonomous driving-ready – or AD-ready – platform should be ready in the next decade, Green says. The timeline for actual autonomous driving beyond that is more vague, and hinges in no small part on how eager Volvo's business partners turn out to be to get driverless technology on the road.

However it's delivered, there's no doubt that Volvo – and the Geely Group in general – isn't sleeping on self-driving's potential. "Compared to a few years ago we have significantly multiplied the number of engineers that work on autonomous driving," Green points out. That includes Volvo's own engineers, and those at Zenuity.

Importantly, it's also willing to share. Maybe not the nuts and bolts of its driverless products, no, but – much in the way that Volvo offered its three-point seat belt technology to the rest of the industry back in 1959 – its broader research and findings, in the hope that collectively the industry will more rapidly work out autonomy's kinks, refine its safety, and hopefully ensure inter-compatibility between vehicles from different brands.

"There is no single player who will crack all the [parts] of this situation," Green points out. Levenstam agrees: it's not just a Volvo without a steering wheel, or a taxi without a driver, he insists, despite short-sighted interpretations of self-driving cars being just that. "We ware seeing one of the biggest changes in mobility right now," the strategist underscores, "and I think we fail to see that."

Volvo's "road planes" are, it's true, unlikely to be plowing up and down dedicated driverless autobahns any time soon. Nonetheless, the automaker is determined. It doesn't plan on waiting around for someone else to invent the technology – or, for that matter, to corner the market in it.