This Huge Void In The Great Pyramid Is A New Egyptian Mystery

If you thought the pyramids had given up all their mysteries, think again. A huge, secret space has been discovered inside the Great Pyramid of Giza, after scientists used new scanning technology to penetrate through the stone. Right now, nobody knows exactly what the chamber is, though speculation has already begun about what it could contain.

One of the so-called Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, the Great Pyramid of Giza is the largest and oldest of the three pyramids in the Giza complex. It's believed to be the tomb of Egyptian Pharaoh Khufu, a fourth dynasty ruler who died in 2566 BC. Archeologists believe it took Egyptian workers 10-20 years to construct, with the final result standing 481 feet high.

It's been a source of constant fascination ever since, not least for its ability to weather thousands of years. Indeed, the pyramid as it stands currently is even less impressive than it would've been in the years following its construction. The weather-worn stones now would have been covered, with smooth casing stones originally cladding the entire surface.

While that much is known, science still isn't certain on how the ancient Egyptians actually managed to build the pyramid. Previous estimates suggested that they'd need to have erected a whopping 800 tonnes of stone every day over two decades. Now, there's another possible spin on that story.

The team, led by Mehdi Tayoubi from the HIP Institute in Paris, used muons to probe the depths of the Great Pyramid. They're created when cosmic rays collide with the Earth's atmosphere, with those collisions with molecules first creating pions that decay into muon neutrinos. Around 10,000 muons reach each square meter of the planet's surface every minute.

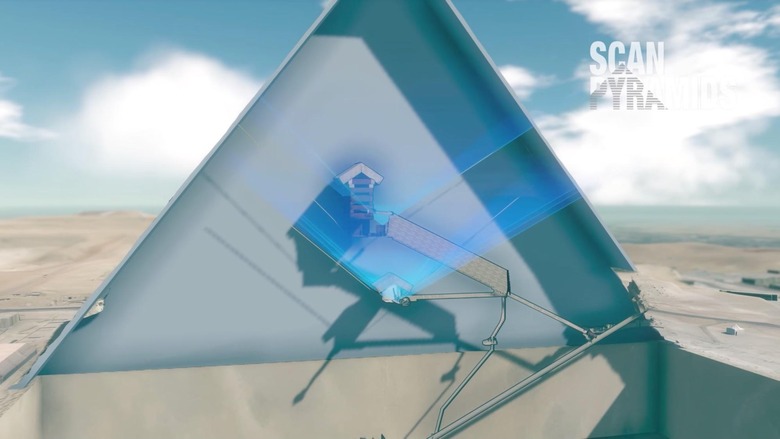

It's how they penetrate into rock that the scientists relied upon for their survey. They're capable of going in deep before being absorbed – up to tens of meters, in fact – which means that, with sensitive detectors set up on the opposite side, by measuring how many muons make it through the pyramid the researchers could build up a 3D scan of the inner structure.

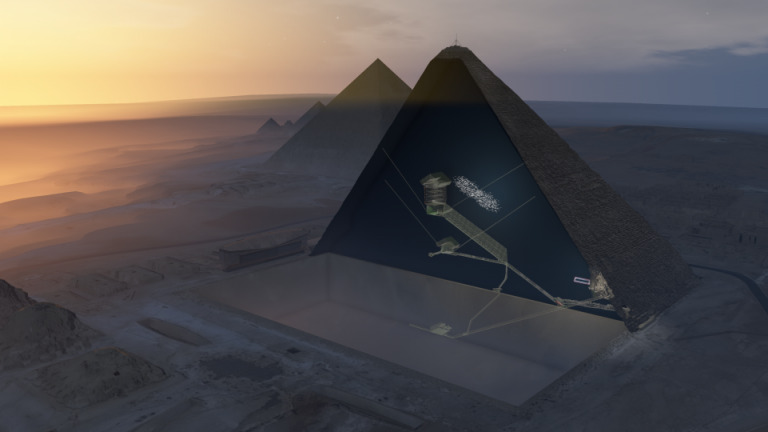

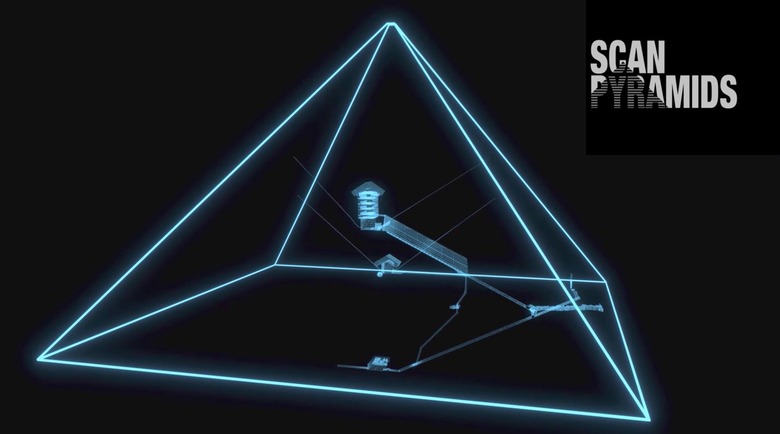

What they found was what's being called the ScanPyramids Big Void. Having first located it with nuclear emulsion films in the Queen's chamber section of the pyramid, the team repeated the process with two other muon-based methods, scintillator hodoscopes in the same location, and then finally gas detectors outside of the structure.

"This large void has therefore been detected with a high confidence by three different muon detection technologies and three independent analyses," Tayouybi and his team writes in a paper published in Nature today. "These results constitute a breakthrough for the understanding of Khufu's Pyramid and its internal structure. While there is currently no information about the role of this void, these findings show how modern particle physics can shed new light on the world's archaeological heritage."

It's no small gap, either. Spanning the same sort of cross section as the Grand Gallery, and running at least 30 meters in length, it's a vast open area in what was previously presumed to be solid rock.

While the researchers may be reluctant to predict what could be inside the void, that hasn't stopped others from making suggestions. The most mundane, of course, is that it was added to the construction for purely practical reasons. Leaving an architectural void would mean less stone was required, thus shortening the construction time.

However, others have put forward ideas of another ceremonial tomb room, potentially, or further treasure spaces. The Great Pyramid's known spaces were thoroughly looted by the time royal tombs began being constructed in what later went on to be known as the Valley of the Kings, though it's unclear if those raiders knew about all of the construction's secrets. So far, the new research hasn't established whether the "Big Void" is one single space, or a series of rooms.

Earlier research of the pyramids has been equally destructive as the looting was, with the muon process having the important benefit of being completely free of damage to the remaining structure. Next up will be figuring out a way – potentially involving tiny exploratory robots – to unlock the secrets of the newly-discovered space.