These Are The WHO's New COVID-19 Variant Names - And Why They're Changing

The World Health Organization (WHO) has announced a new system for naming COVID-19 variants, aiming to cut out the current practice of referring to them by the location they were first identified. The new labels will instead use the Greek alphabet, in a step to address what some have criticized as unnecessary stigmatization.

Existing scientific names for the coronavirus will remain, even under this new system. However the WHO is hoping to replace the unofficial tendency to refer to the COVID-19 variants and mutations by country name, such as "the UK variant."

"While they have their advantages, these scientific names can be difficult to say and recall, and are prone to misreporting," the WHO argues. "As a result, people often resort to calling variants by the places where they are detected, which is stigmatizing and discriminatory. To avoid this and to simplify public communications, WHO encourages national authorities, media outlets and others to adopt these new labels."

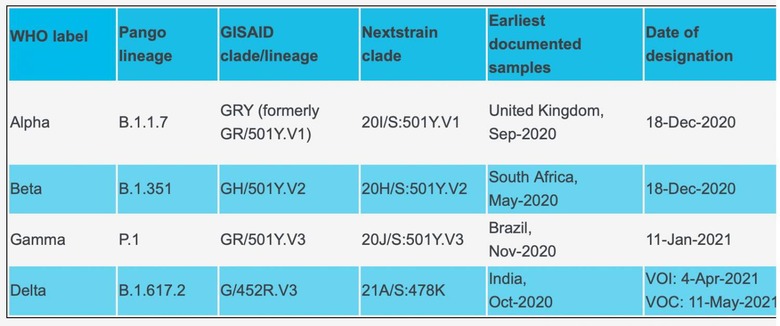

The "United Kingdom variant," for example, would be known as the Alpha variant under the WHO's new system. The country would merely be referred to as the location of the "earliest documented samples."

The strain of COVID-19 with the earliest documented samples originating in South Africa, meanwhile, will be the Beta variant, while the version identified first in Brazil will be Gamma. Finally, of the four "Variants of Concern," the strain first identified in India will be the Delta.

To be a "Variant of Concern," the strain needs to show either an increase in transmissibility or detrimental change in COVID-19 epidemiology; or an increase in virulence or change in clinical disease presentation; or a decrease in effectiveness of public health and social measures or available diagnostics, vaccines, or therapeutics.

There are also currently six "Variant of Interest," two of which were first identified with samples in the USA.

Uncertainty about the potential impact of the COVID-19 variants has continued throughout the pandemic, with particular concern around how effective current vaccines will be to new, upcoming strains. Currently, the general assumption is that yearly booster shots may well be required, much in the same way that annual flu shots are a fact of life to deal with each winter season's most dangerous strains.

In May, for example, Dr. Fauci – director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases in the US – said that vaccine efficacy "lasts at least six months, and likely considerably more." However, the government advisor also cautioned that "we will almost certainly require a booster sometime within a year or so after getting the primary."