The Wearable Medic: GERO And Figuring Parkinson's From Fitbit

There's a suspicion among many that wearable tech is simply today's digital navel-gazing; a self-indulgent and meaningless set of metrics bordering on narcissistic over-obsession. The quantified self could soon become a whole lot more meaningful, however, if startup GERO has its way. Building on groundbreaking research by the Human Locomotome project, the Russian company says it can use the data from wearables like Fitbit's Force and Jawbone's UP to identify chronic conditions such as Parkinson's, Alzheimer's, depression, and even type 2 diabetes, simply from the way we move. SlashGear caught up with GERO's co-founders at CES as they shift things out of stealth mode.

Today's fitness wearables are, for the most part, relatively limited. While they track metrics like number of steps taken, distance traveled, and even calculate calorific burn and light/deep sleep cycles, they generally leave any conclusions or more detailed interpretation of that data to the user themselves. Some firms have tried to be a little more proactive with their analysis – Jawbone's UP24, for instance, creates custom goals depending on behavioral patterns over the past few days – but it's still relatively tame stuff, like nudging you to move when you've been sitting for extended periods, or encouraging you to sleep more.

The research on which GERO is based, however, goes beyond that exponentially. The Human Locomotome project found that tiny changes in body movement – unnoticeable in real-time – could be accurate predictors of chronic diseases, whether metabolic, psychiatric, or psychological, both in terms of early diagnosis and in monitoring how conditions are evolving.

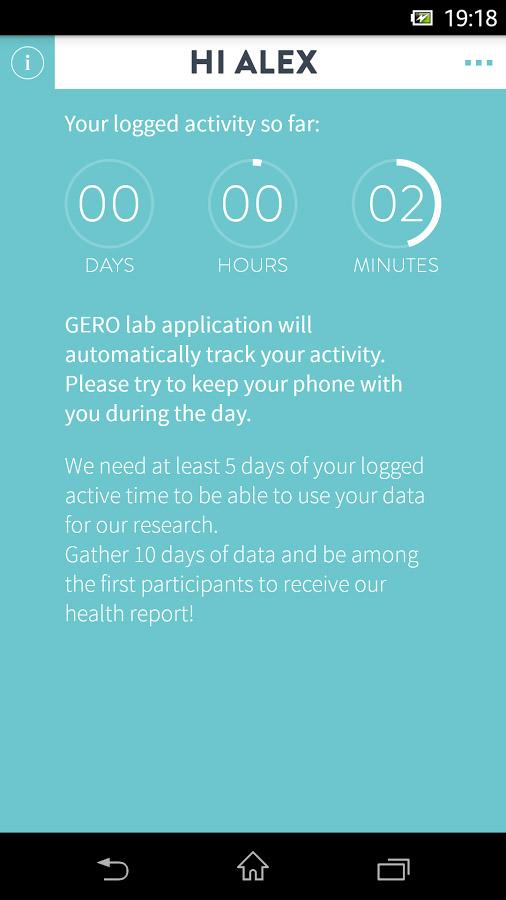

By tracking those changes, GERO says, it can identify a surprising range of conditions: type 2 diabetes, depression, hypertension, Parkinson's, Alzheimer's, schizophrenia, and more. The low-resolution movement sensors in wristbands like UP and Force take around a month of monitoring before they have sufficient data from which to make an early diagnosis, but even with off the shelf consumer-level hardware the model still works.

"It's like magic" we joked with Igor Mikhnenko, GERO's co-founder and CMO, something he's heard – and argued against – on multiple occasions as the company has discussed the system with healthcare professionals during its development.

"We've been to medical exhibitions, and some of those medical guys they think of us like astrology or something" Mikhnenko explained. "But when we jump into a conversation with them, they discover that our chief scientist actually is from the drug discovery business, he's the author of several AIs, mathematical models, and he applies the same physics, the same system methodology."

That chief scientist and fellow co-founder is Peter Fedichev, a PhD physicist whose areas of expertise span the fields of biophysics, drug design, and condensed matter physics. The jump from that to personal health telemetry came with a phase one study of 3,000 Fitbit users in 2013, comparing the predictions the model made based on movement metrics versus known conditions the sample group reported.

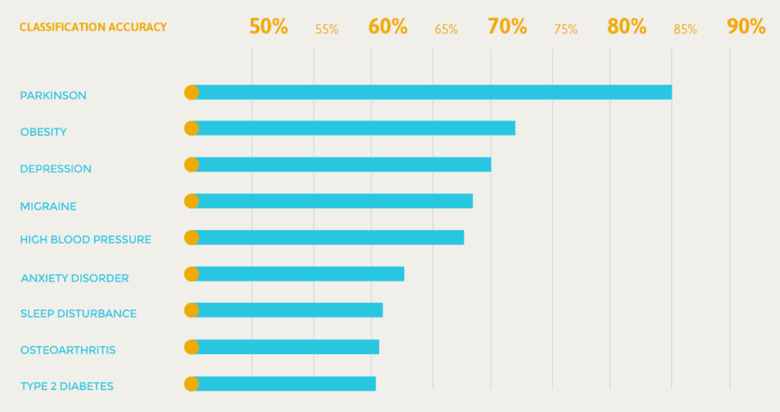

GERO's results make for surprising reading. Most easily identified is early-onset of Parkinson's, with around 85-percent classification accuracy, while predictions of depression, migraine, high blood pressure, anxiety disorder, sleep disturbance, and osteoarthritis all fall within the 60- to 70-percent bracket.

Solid predictions are one thing; part of the next challenge is finding a way to turn that into a business. That's where Mikhnenko and GERO CEO Vera Kozyr came in, fresh from having developed the first YotaPhone, the dual-sided smartphone that launched at CES 2013 with an LCD on one side and e-paper on the reverse. Having left the company last year, they founded GERO and have begun talks with wearables players to discuss how to integrate the company's models into the metrics each offer.

The goal, Kozyr says, is to effectively democratize early-onset diagnosis in a way that makes health far more transparent. Although GERO is meeting with several of the big names in fitness tracking, both Mikhnenko and Kozqyr are adamant that they don't want an exclusive agreement with any one firm.

In fact, they're quick to praise those in the wearables space that take a more open approach to accessibility of data, giving particular props to Fitbit for its API. Many providers, in contrast, are far more silo'd with how they treat their database, to the point that the wearers of the health trackers often don't realize who owns the information they're generating, and who it's being sold to.

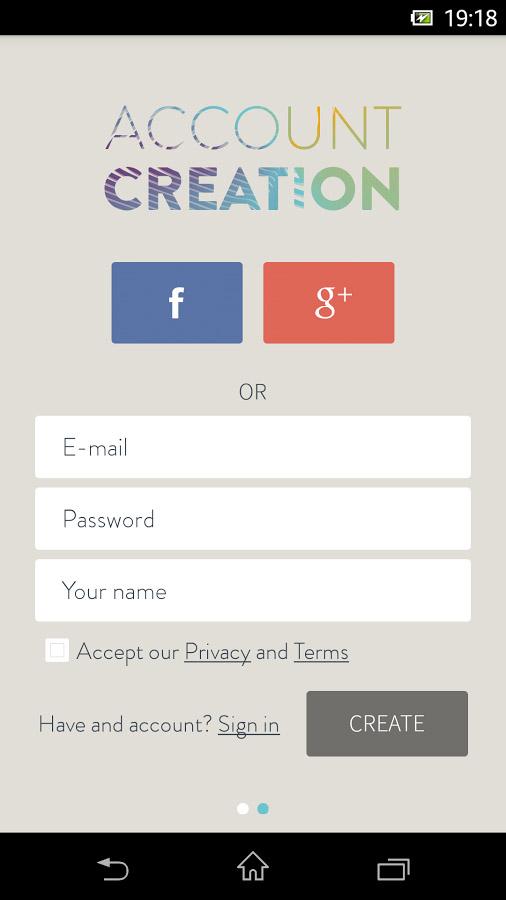

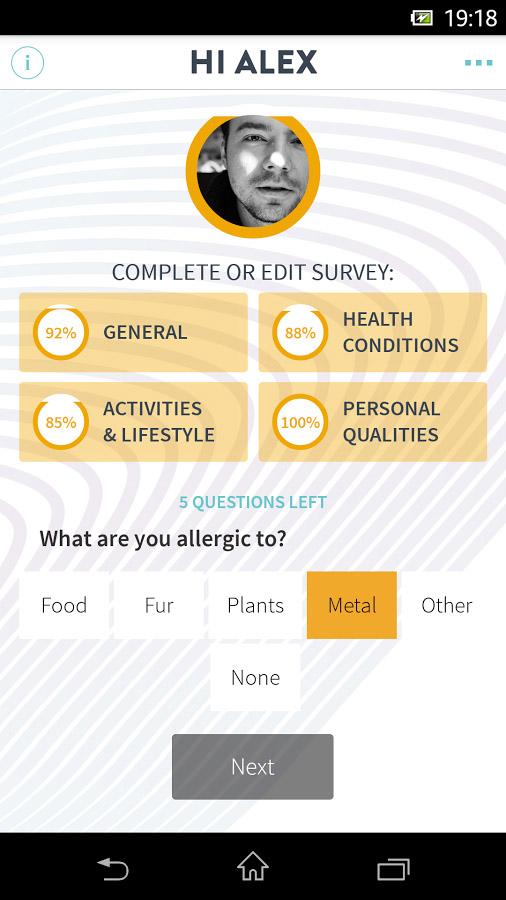

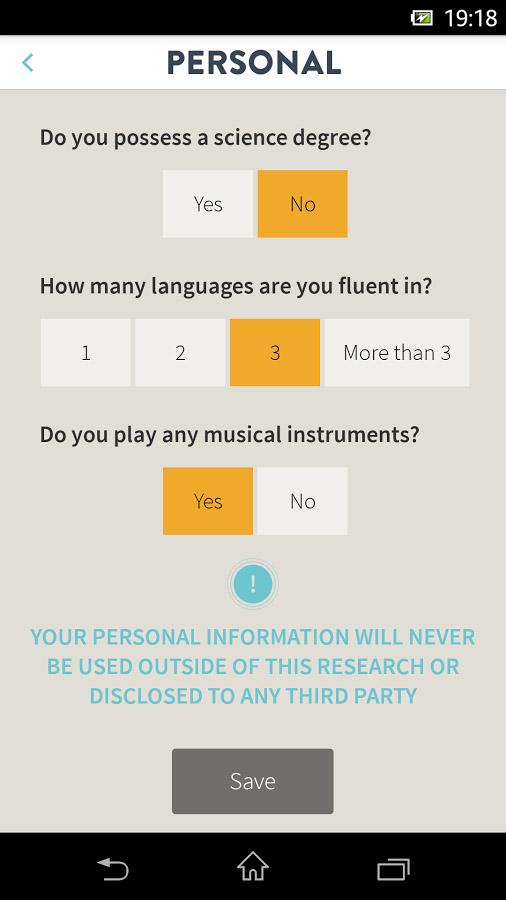

GERO's first step toward that is GERO Lab, a "crowd-research" wearable 2.0 platform which will kick off phase two of the company's research. By engaging existing wearables users – either with a Fuelband, Jawbone UP, one of Fitbit's devices, or a BodyMedia armband – and allowing them to share their data with the project, GERO hopes to expand its trial pool to around 50,000. Those who don't have a tracker can still take part, with GERO having developed a free smartphone app that uses the sensors in Android handsets and, eventually, the iPhone to collect data too.

GERO Lab won't, initially, make any predictions on chronic conditions: it's being used as a method to dramatically increase the number of participants in the program and refine the accuracy of the model. The company is especially keen to involve those with pre-diagnosed health issues so that they can track how well the system copes as those conditions evolve.

It's that long-term value that could help turn wearable tech from being a geek's gimmick to a legitimate, long-term business. Whereas many wearers quickly get disillusioned with their fitness trackers, eventually leaving them uncharged and unworn in a drawer after the novelty of counting steps wears off, the promise of being able to flag up new conditions early, not to mention monitoring known conditions and see whether they're improving or worsening, makes keeping a wearable on more legitimate.

There's still plenty to be worked out as the second phase – expected to run for around six months – gets underway. Unclear for instance is how the health results will be fed to the individual wearers: GERO recognizes that there's a big responsibility around making diagnoses, and Mikhnenko says the company intends to apply for FDA approval so that it can take on the medical aspect of providing advice rather than, say, Fitbit or Jawbone.

The team will also be working on highlighting just how much can be derived from smartphone sensors, such as the M7 coprocessor in Apple's iPhone 5s. In fact, GERO has a new paper coming out soon which will specifically address smartphone sensor resolution; a step up in refresh frequency could also deliver big results, potentially trimming the diagnosis time down to around a week.

Beyond that, though, it's about convincing people – whether in healthcare, in wearable tech, or in the audience looking on the segment with mixed degrees of suspicion – that you can derive meaningful information on serious medical issues from something perceived as so basic. GERO's Mikhnenko is happy to credit the wearables manufacturers for all they've done so far, but thinks that it's time to shift things up to the next level.

"All of these guys, we really adore them, because they created a beautiful wearable trend and people can be aware of how they move, what they do – they developed the industry from zero – and right now it's a huge trend" he concluded. "But what we believe in is what should be the next step: we call ourselves wearable 2.0."