T-Rex's Serrated, Folded Teeth Used Like Near-Unbreakable Knives

Theropod dinosaurs like the Tyrannosaurus Rex have been known to have serrated teeth for some time – today it's apparent why. A study has been published this week by lead author Kirstin Brink, a postdoctoral researcher of biology at the University of Toronto Mississauga, which shows how theropod teeth aren't just shaped the way they are to keep them from breaking under pressure, they're made to tear apart flesh the same way our modern knives are today. This awesome feature allows dinosaurs who have it to rip into meaty flesh from birth.

Brink and her team used a scanning electron microscope as well as a synchrotron to get in up close and personal with ancient teeth and determine their chemical compositions. What they found was that though some very old animals (like the Dimetrodon) also have serrated teeth, it was dinosaurs like T-Rex that had the ideal chemical makeup in teeth to both shape and maintain denticles (serrations) through the life of each tooth.

This is ziphodonty, the presence of serrations (denticles) on the cutting edges of teeth.

ABOVE: Adrian Dennis/AFP/Getty Images

Internal structures evolved over time – while the Dimetrodon had serrated teeth back in the Paleozoic era, before dinosaurs, it was dinosaurs that had the chemical makeup in their teeth required to KEEP these micro-cuts. Each structure studied in a number of theropods had layers of dentine under the tooth's outer enamel.

They were tough as they were sharp.

Inside each tooth were deep folds, strengthening each serration for best-in-class retention of sharpness.

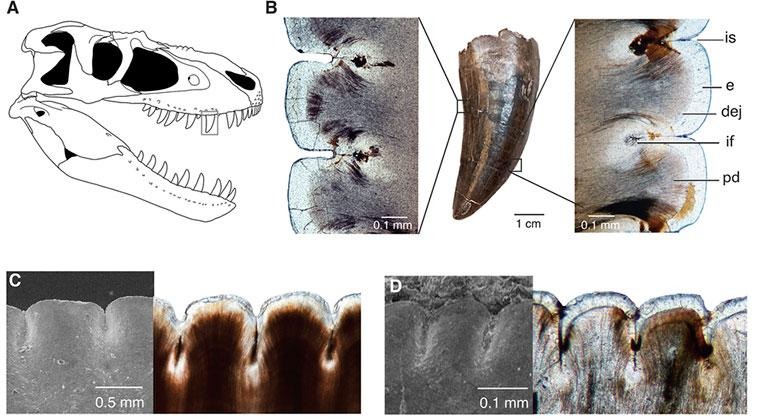

Above via Nature: (A) Skull of Gorgosaurus libratus, a tyrannosaurid dinosaur, drawn by Danielle Dufault. (A) Skull of Gorgosaurus libratus, a tyrannosaurid dinosaur, drawn by Danielle Dufault. (B) Complete tooth (ROM 31535) and sagittal thin sections through distal and mesial carinae of a maxillary cf. Gorgosaurus sp. (ROM 57981) tooth. (C and D) carinae of ziphodont teeth under SEM (left) and in thin section (right). (C), Indeterminate phytosaur, ROM 7981, mesial carina. (D) Coelophysis bauri, CM 76863, distal carina.

Brink and crew also found that these serrations began forming below the gum line. This discovery ends the hypothesis made previously which suggested that these serrations were actually chips and cracks in the tooth, made by prolonged chomping of meat and everyday damage.

The only creatures known to still have this ziphodonty feature in their teeth are varanid lizards. This family of lizards includes the Komodo dragon and the crocodile monitor. These creatures no longer retain the extra folds that would allow them to rip through the layers of tough flesh their ancestors devoured daily.

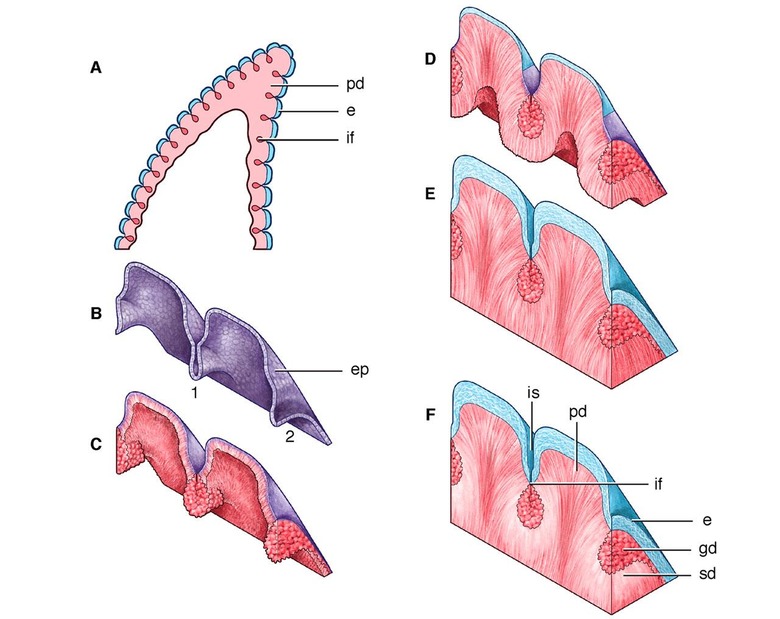

ABOVE: (A) Mineralization of the tooth tissues from tip towards the root. (B) Detail of two denticles, showing deposition of tooth tissues in 1) sagittal and 2) transverse views. Dental epithelium folds to form the shape of the tooth prior to differentiation of tooth tissues. (C) Dentine deposition by odontoblasts. Globular mantle dentine deposition in the interdental fold and the remainder of the tooth, and mantle dentine in the denticle tip. (D) Enamel deposition by ameloblasts at each denticle tip; primary dentine deposition. (E) Enamel mineralization into each interdental sulcus, stopping before closing the channel at the interdental fold in the dentine. Tooth eruption occurs at this stage. (F) Functional tooth with sclerotic dentine deposition. Abbreviations: e, enamel; ep, epithelium; if; interdental fold; is, interdental sulcus; pd, primary dentine; sd, sclerotic dentine. Colors: blue, enamel; purple, epithelium; red, dentine; white, sclerotic dentine.

You can learn more about this subject in the paper "Developmental and evolutionary novelty in the serrated teeth of theropod dinosaurs" as authored by K.S. Brink, R.R. Reisz, A.R.H. LeBlanc, R.S. Chang, Y.C. Lee, C.C. Chiang, T. Huang, and D.C. Evans. This paper was published on the 28th of July, 2015, in the scientific journal Nature under code doi:10.1038/srep12338.