Subscription On Apps Are The Unavoidable Future

Apple may have seen the writing on the wall. Google may have actually sensed it sooner, which is why it didn't seem to get excited in the first place. Although they have been the biggest proponents of this app-centric ecosystem we have today, especially on mobile, the two most influential companies in the world seem to be slowly abandoning them. Apps are no longer the great money makers they once were, even the paid ones. Some might argue they never were, at least on Android. The money may soon be in subscriptions instead, and that could drastically change the software landscape forever.

Subscription-based software isn't exactly new even if most people will most likely associate recurring monthly or annual payments more with access to digital content, like videos and music, or at least with Internet-based services like cloud storage or even office suites. But one only has to look to Adobe's Creative Cloud, launched way back in 2012, for software whose very access itself depends on user paying a regular fee.

Young as it is, the mobile ecosystem has adopted a more traditional model similar to that of most PC software and games. You either get the software for free or you make a one-time payment and that's it. You could pay extra later on for DLCs or addons but, as far as being able to use the app in its entirety, that contract has been signed, sealed, and delivered, so to speak.

While that has worked before, it may no longer be a sustainable model these days. At least not for software developers and especially not for app store distributors who take a cut from every sale and renewed subscription the apps make. The mobile app ecosystem has also made three-digit price tags on software look totally ridiculous. Even two-digit prices on apps are seen asking too much, especially on mobile. Developers and distributors have, therefore, tried to search for a way to balance the cheaper prices the market expects with a business model that won't force them into bankruptcy.

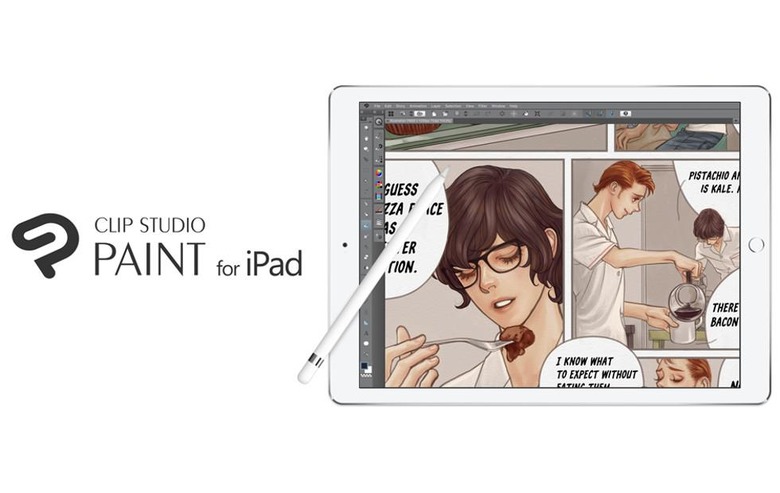

That compromise might be in software subscriptions, not just for cloud features (though that will most likely become part of it) but for access to the apps themselves. At first blush, this might not make sense, mostly because it runs contrary to what we've become used to as far as non-services software is concerned. Why should you pay a recurring fee for a program you've already bought? That resistance and confusion can be seen both in Adobe' CC as well as the Clip Studio Paint's iOS launch which, unlike its desktop counterpart, required an active subscription to unlock majority of its features.

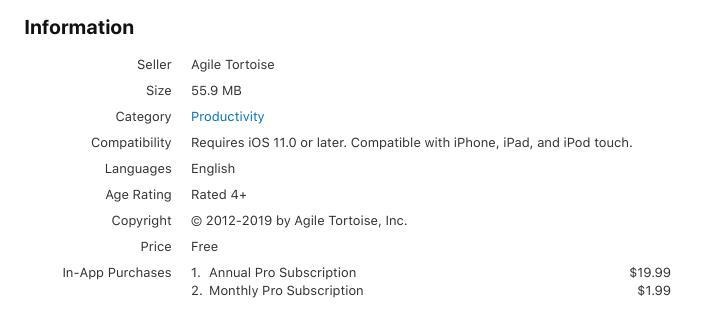

The business model does have advantages for everyone, though. Obviously, software developers will get a steadier revenue stream compared to one-off payments that can quickly run dry. This also means that app stores will also have a steady stream of cuts. The benefits to the end user is mostly indirect, as a subscription, in theory would both motivate and commit developers to regularly deliver updates and fixes to justify the recurring costs. It's pretty much "software as a service" on a smaller scale.

However, it's not a perfect solution for all players. Developers have to think harder about the right price for their recurring fees. Too high and it will scare off users. Too low and even recurring revenue won't be enough to offset the costs. They will also be more pressured to keep up the development pace to justify the subscriptions. And users will have to hope that developers will indeed deliver on that.

Apps and app stores are already heading in that direction, especially on iOS. Some major apps have already adopted a subscription model regardless of whether they offer cloud-related functionality or not. Apple itself has been reportedly talking with developers to convince them that subscriptions are the way to go. While Google hasn't made such huge strides, it's attitude has always seemed to favor services, and therefore recurring subscriptions, over apps. After all, services integrate better into its search and AI systems better than locally installed apps.

The inevitable shift to subscription-based software does highlight something that has been true for decades now but something users probably take for granted. You don't own the software you paid for. What you're buying, instead, is the license to use the software, and even those still come with limitations. Think of it like a perpetual non-recurring subscription. With subscription-based software access, that becomes even more obvious. This time, it's plain you aren't buying anything, software or license. They own the space and you're just renting it.