SpaceX Starlink Satellites Won't Outshine Science Insists Elon Musk

Starlink may only have a fraction of its planned internet satellites in orbit so far, but questions are already being raised as to how SpaceX's globe-blanketing connectivity system will avoid interfering with astronomy and stargazing. The company launched its first sixty Starlink satellites last week, part of a network of coverage that Elon Musk's project expects to bring connectivity to users all over the world.

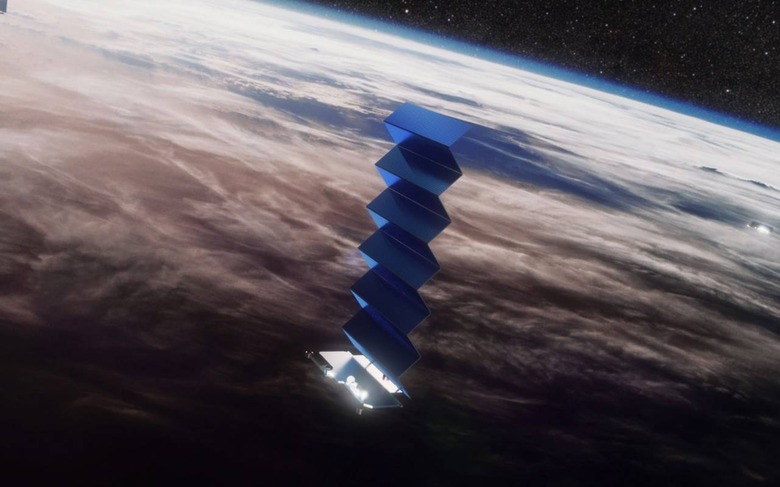

Starlink will be, eventually, a constellation of low Earth orbit (LEO) satellites. Each weighs approximately 500 pounds, and is shaped like a flat panel; that allows SpaceX to maximize the number it can include in each Falcon 9 rocket launch.

Once launched, the satellite unfurls a single solar array which is used for day to day power. There's also a set of ion thrusters – powered by krypton – that can be used for repositioning. Those same thrusters allow each Starlink satellite to move out of the way of a potential crash with debris or other spacecraft, and indeed to deorbit, burning up in the atmosphere in the process, at their end of their life.

Eventually, SpaceX plans to have around 12,000 Starlink satellites deployed. That has raised concerns among the scientific community as to how much of an impairment the network could end up representing to astronomy and other research. Part of the concern is how much light might be reflected off the solar arrays.

Just how bright that could be was shown in a video last week, showing a string of satellites gleaming like pearls. It prompted fears that the brightness would be considerably more noticeable than SpaceX initially suggested. Indeed, those early passes led some to predict that as many as 500 of the satellites could be visible in the night sky at any time.

Happily, subsequent passes suggested those initial observations were atypical, as satellites went through the process of orienting their solar panels to face the sun. Enough, indeed, to drop the light down to magnitude 5 from magnitude 2: the brighter an object, the lower the number. "That is still brighter than we had expected and still a problem, but somewhat less of a sky-is-on-fire problem," Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics astronomer Jonathan McDowell observed.

On Twitter, Elon Musk responded to concerns from the scientific community. "There are already 4900 satellites in orbit, which people notice ~0% of the time," he wrote. "Starlink won't be seen by anyone unless looking very carefully & will have ~0% impact on advancements in astronomy. We need to move telescopes to orbit anyway. Atmospheric attenuation is terrible."

However Musk isn't waiting for telescopes to be moved; after all, Starlink's satellites themselves can be dynamically placed. "If we need to tweak sat orientation to minimize solar reflection during critical astronomical experiments, that's easily done," he pointed out.

The whole brightness issue is something SpaceX is considering, Musk continued. The exec "sent a note to Starlink team last week specifically regarding albedo reduction," he tweeted. "We'll get a better sense of value of this when satellites have raised orbits & arrays are tracking to sun."

Starlink says it hopes to launch internet service in the Northern US and Canadian latitudes after six launches. Its current roadmap has as many as six launches to be completed by the end of the year, though a more conservative estimate is two. Global coverage of the populated world won't be achieved until 24 launches, the company says.