NASA Mars Helicopter Prepares For Flight - And UAVs On Earth Could Benefit

NASA's 2020 mission to Mars won't just depend on landing on the red planet to be successful: the Mars Helicopter also plans to take off again. The space agency has been discussing its plans to send a groundbreaking helicopter into space, and while the spindly drone may not be scaled to accommodate a human passenger, the technology behind it could well have implications for transportation back on Earth.

The idea of sending a helicopter to Mars was first broached back in 2015, with NASA envisioning the aircraft supporting ground-based rovers with a new layer of data. It wasn't until 2018, however, that the addition to the 2020 Mars mission was given the green light.

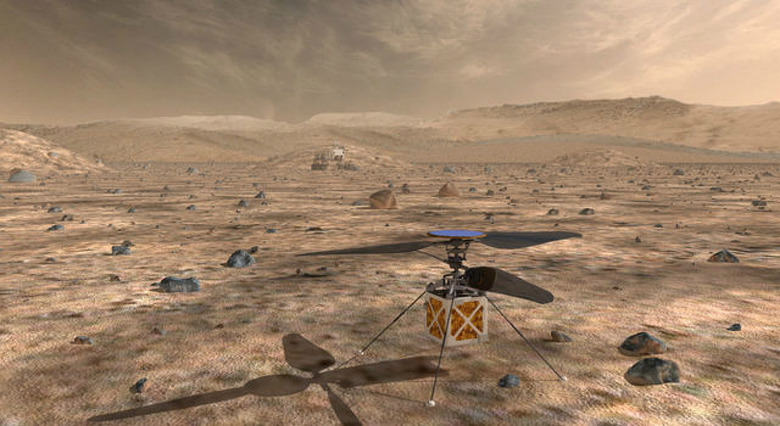

Although dubbed a helicopter, the craft actually has just as much in common with a high-tech drone. A traditional helicopter has a primary rotor that spins horizontally, and a smaller tail rotor that rotates vertically to counteract the torque that would otherwise cause the whole thing to spin around. The Mars Helicopter, in contrast, will use a co-axial design, with two similarly sized counter-rotating rotors stacked one atop the other.

Those rotors will each be roughly four feet long, tip to tip, and spin at 2,400 rotations per minute. That's around ten times the speed of an Earth helicopter, a reflection of the extra effort needed for the craft to fly in Mars' thin atmosphere. Indeed, given the atmospheric pressure at the proposed Mars 2020 landing size is equivalent to around 100,000 feet above the Earth's surface, it would mean the Mars Helicopter would be flying at altitudes no terrestrial chopper has ever reached.

Because the latencies involved in remotely piloting it from Earth would simply be too great, NASA will need to give the Mars Helicopter a brain of its own. The Revolutionary Vertical Lift Technology (RVLT) project is working on an autopilot system that will enable it to avoid obstacles, handle unexpected shifts in atmospheric conditions, or indeed deal with its own technical issues. If need be, the aircraft is designed to safely drop to the ground.

Indeed they're similar challenges to those a "flying car" might face, another project that a different team at NASA is working on now. The Urban Air Mobility (UAM) project is looking to develop autonomous flying craft that could carry people and cargo around cities, and which would need to be similarly equipped to make split-second operational and safety decisions without human intervention.

While the two teams are separate for now, NASA says there are clear parallels between their work, and the long-term implications of each project.

"Looking to the future, if the Mars Helicopter works as planned, JPL scientists say future missions to the Red Planet could carry and deploy even more helicopters to extend the scientific reach of the landers they arrived on," the space agency suggests. "Should that happen, and the skies of Mars start to get a little busy with autonomous helicopters flying about, parts of a drone-related traffic management system descended from work being done today by NASA Aeronautics also could find a home on the Red Planet."

Initially, though, the Mars Helicopter will be a lone occupant of the skies above the red planet. With its body roughly the size of a softball, and an overall weight that tips the scales at under four pounds, it's a far cry from the sort of flying vehicle NASA and others have in mind to change urban transportation and deliveries back on Earth. Its flight times will reflect that, too: NASA expects to make just five flights at most, each lasting up to 90 seconds in duration, with the Mars Helicopter relying on solar panels to charge up its batteries.

While that may sound conservative, it'll actually be a huge step forward given our current track record in space exploration. "The Mars Helicopter's initial flight will represent that planet's version of the Wright Brothers' achievement at Kitty Hawk and the opening of a new era," Susan Gorton, NASA's manager for the RVLT project, said. "For those of us whose research revolves around all things related to flight, that would be a remarkable, historic moment."