NASA Launches Space Station Lifeboat Project

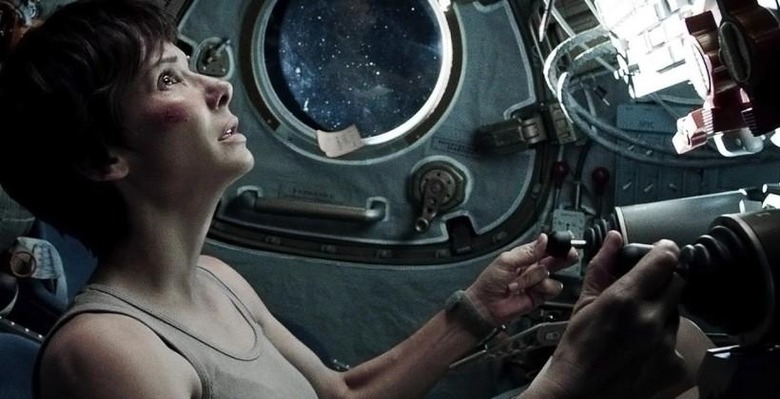

If Sandra Bullock in Gravity proved anything, it's that George Clooney is smug even in space and that having an emergency exit back to Earth is probably a good thing. NASA is now working on the latter, with plans to equip the International Space Station (ISS) with a dedicated lifeboat for the first time in forty years, giving the orbiting crew there a place to not only shelter from incidents on the platform, but a way to escape it should something go seriously wrong.

The US space agency has thrown over the challenge to aerospace companies, with Boeing, Sierra Nevada Corporation, and SpaceX all working on potential lifeboat designs.

While it may seem straightforward, in fact the technical hurdles facing the project are considerable. Most pressing, perhaps, is the balance between capabilities and power consumption, given the ISS needs to be self-sufficient.

In fact, NASA can only spare about the same amount of juice as would be used by a domestic refrigerator to the ISS' lifeboat, despite requiring it to support a crew for at least 24hrs while still docked.

Although shutting it down altogether when not needed would be the obvious way of circumventing that issue, in practice it's not as simple. Without active air circulation, NASA explains, pockets of airless space can build up: that could ironically see astronauts fleeing the ISS entering the lifeboat, only to black out because of a lack of oxygen.

Other considerations are equipping the pod with sufficient shielding to withstand minor micrometeorite impacts, but not so much that it's then too heavy to actually escape the station itself.

The ISS' current evacuation process is served by Russian Soyuz spacecraft, two of which are permanently docked. Each can hold up to three astronauts, limiting the total compliment of the space station to six people at most at any one time.

New designs under consideration, however, could have as many as seven more seats to space, potentially allowing for a crew twice the size as is safe today. The result would be faster research, since more scientists could be present simultaneously.

SOURCE NASA