Mesmerizing "Lucky" Jupiter Image Reveals Monumental Storm Secrets

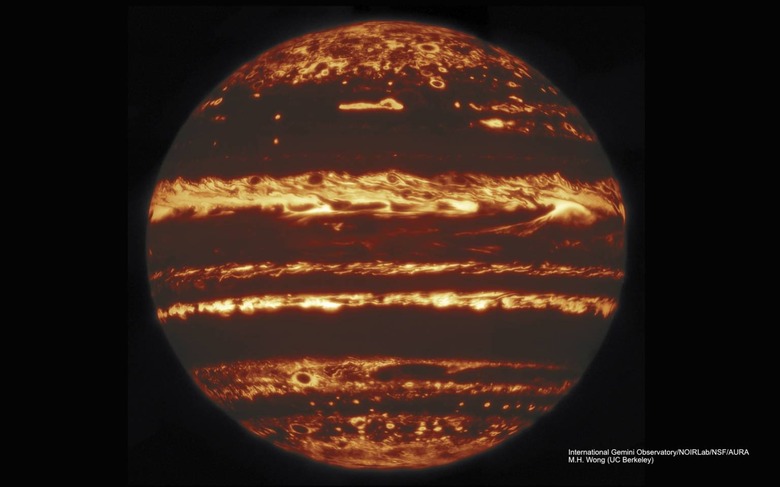

Groundbreaking new images of Jupiter have pieced together a "lucky image" of the mysterious planet, giving astronomers unprecedented insights into the fierce storms that churn the gas giant's clouds. Using the Gemini North telescope on Hawaii's Maunakea, a mosaic of shots designed to bypass the effect of Earth's atmosphere allow us to see Jupiter as if we were in orbit around it.

Though it may be the largest planet in our Solar System, getting a clear shot of Jupiter still isn't an easy matter. Earth-based telescopes have high resolution, and Gemini's Near Infrared Imager (NIRI) can actually look into the planet's storms, but instabilities in Earth's own atmosphere can blur the final results.

Instead, a team working with Gemini and the Hubble Space Telescope used what's known as "lucky imaging" to get the best possible results. Nine separate pointings at Jupiter took place; each consisted of 38 exposures. Scientists sifted through the results and selected the sharpest 10-percent, which were then combined into a single, final image.

That required careful positioning of the composite images to line up correctly, since Jupiter would rotate as the exposures were captured. The result, however, is among the highest-resolution infrared view of the planet ever recorded from the ground.

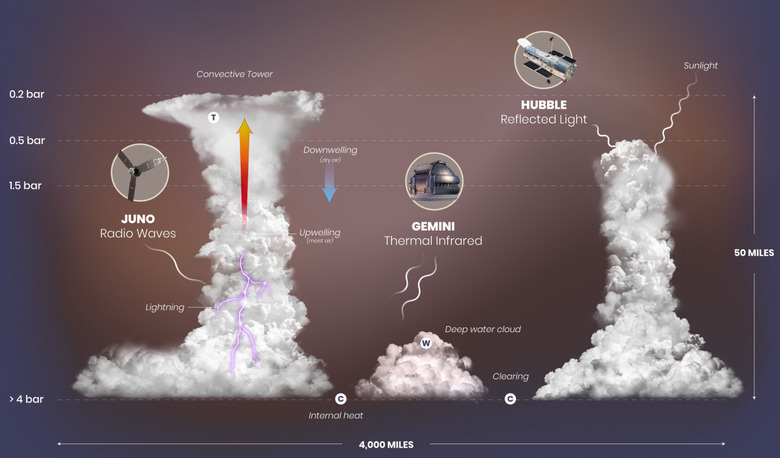

This wasn't just all in aid of making a beautiful image, however. Researchers wanted to explore how the observations of the Juno orbiter matched up with the science behind the huge cyclones, atmospheric waves, and wind patterns on the distant planet. For example, Juno caught the radio signals generated by lightning flashes from its position in orbit; then, images across multiple wavelengths from Gemini and Hubble could be compared at those times and locations.

"By combining these three pieces of information," the researchers at Gemini say, "the research team found that the lightning strikes, and some of the largest storm systems that create them, are formed in and around large convective cells over deep clouds of water ice and liquid."

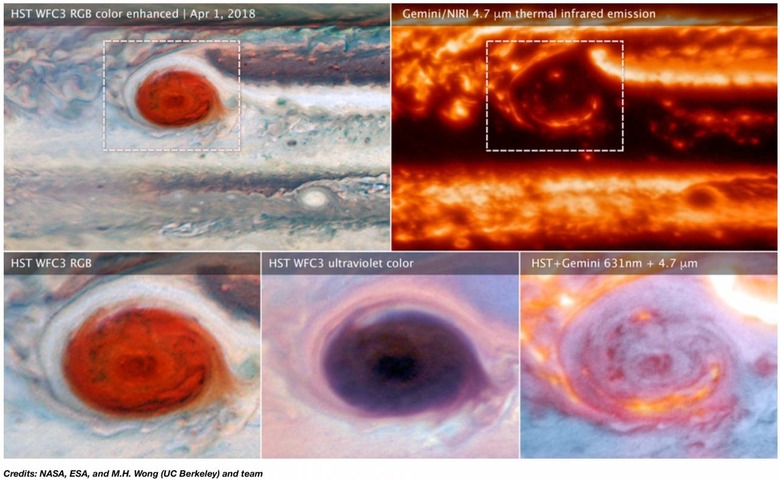

The most aggressive lightning was observed from a swirling storm known as a "filamentary cyclone," into which images from Hubble and Gemini could peer down. That turned out to be a twisted collection of tall, convective clouds. Deep gaps revealed the water clouds far below that, with observations across a variety of wavelengths allowing for 3D models of the cyclones to be created.

In the process, the researchers may have addressed one of the biggest questions about Jupiter, and its Great Red Spot. That's been observed glowing in the past, "but visible-light observation couldn't distinguish between darker cloud material, and thinner cloud cover over Jupiter's warm interior, so their nature remained a mystery," Glenn Orton of JPL explains.

Hubble couldn't see what was happening in visible light, but Gemini's infrared visuals revealed a bright arc lighting up the whole region at the Great Red Spot. That means there are, indeed, gaps in the clouds there, allowing heat from the interior to stream through.