Meet Wonderchicken, A Paleontology Marvel. No, Seriously

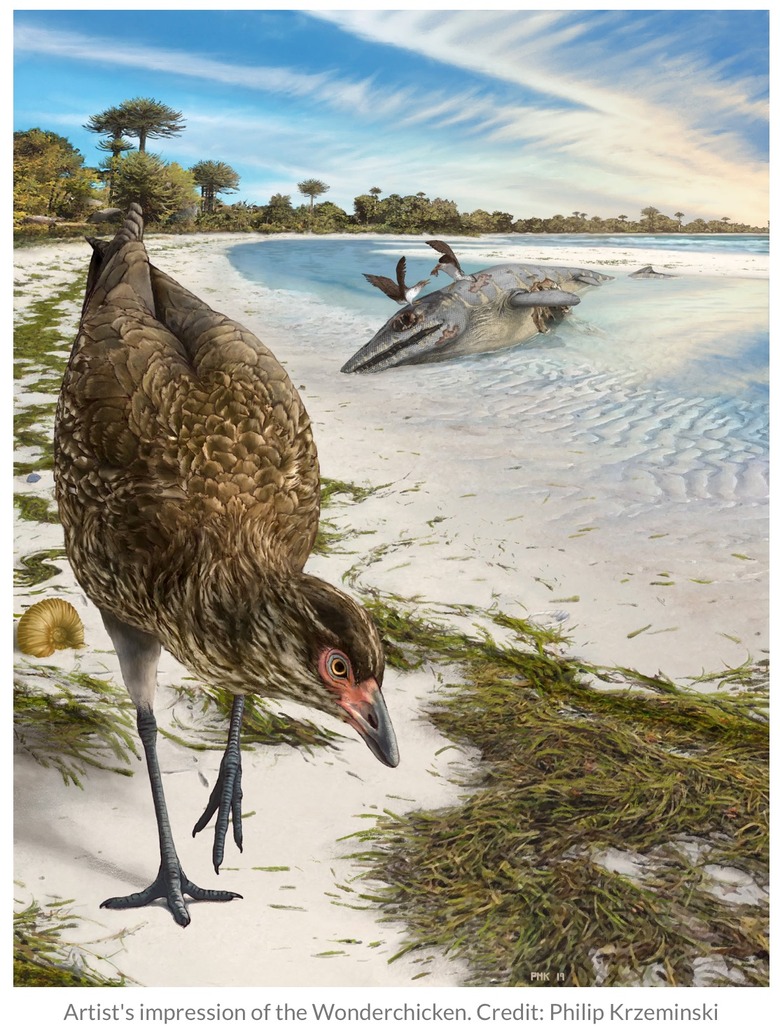

Paleontologists have stumbled across the oldest fossil of a modern bird identified to-date, and while the name they've given it might be silly, the implications for this "Wonderchicken" are incredibly serious. Spotted in a limestone quarry in Europe, the skull could help fill in gaps about how certain species survived the mass extinction event that killed off the dinosaurs.

While that event is believed to be an asteroid strike, leaving the dinosaurs facing a new ice age and shortages of food, the destruction to nature wasn't the same across the board. Though the dinosaurs may have died out, other species of animal managed to survive through the long changing seasons.

Chunks of rock from a limestone quarry near the Belgian-Dutch border probably wouldn't be the first place you'd expect to find something helping fill in those blanks, but that's just what has happened. Researchers from the University of Cambridge discovered a nearly complete skull inside them, believed to date from less than one million years before the asteroid impact. It could well be close to the last common ancestor of modern chickens and ducks.

That's because it combines features familiar from both modern species, and left the research team to name it the "Wonderchicken." High-resolution X-ray CT scans allowed the contents of the rocks to be investigated, without having to crack it open. That turned out to be a good thing, because the skull remains were just a millimeter below the surface.

The scull itself is around 66.7 million years old, and – according to team lead Dr Daniel Field, "one of the best-preserved fossil bird skulls of any age, from anywhere in the world."

Its official name is Asteriornis, a reference to Asteria, the Greek Titan goddess of falling stars. The remains' location is another surprise, given bird fossil history from Europe is sparse for the late Cretaceous period. "This fossil tells us that early on, at least some modern birds were fairly small-bodied, ground-dwelling birds that lived near the seashore," Dr Field explains.

More research will need to be undertaken to fully understand the implications of the fossil. However the hope is that, now that this first skull has been discovered, evidence of others still out in the wild – or potentially already in collections – will be easier.

"Its occurrence in the Northern Hemisphere challenges biogeographical hypotheses of a Gondwanan origin of crown birds," the researchers' study published in Nature today suggests, "and its relatively small size and possible littoral ecology may corroborate proposed ecological filters that influenced the persistence of crown birds through the end-Cretaceous mass extinction."