Man Vs Machine: I Raced Against Audi's Self-Driving RS 7

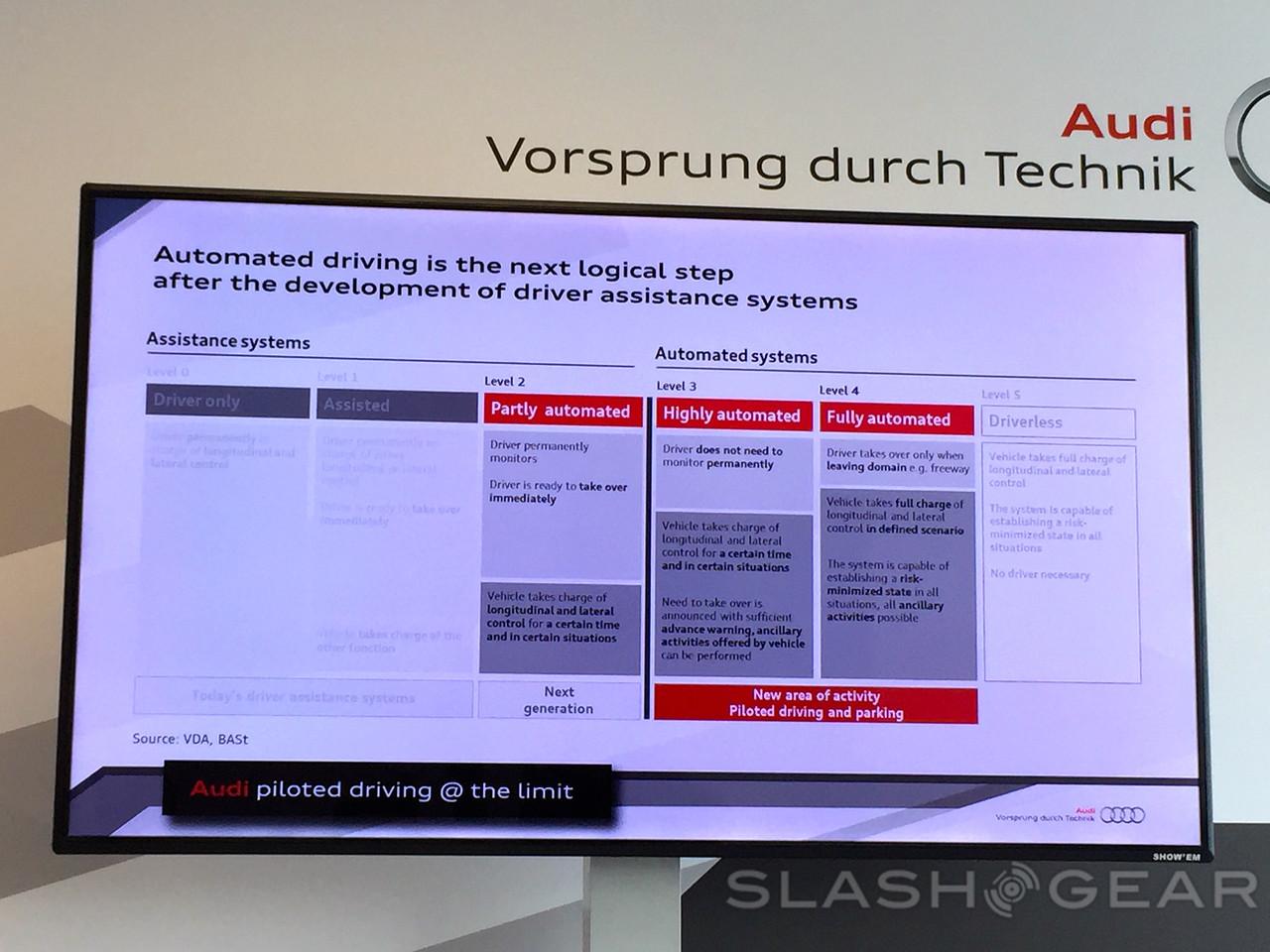

When it comes to proving the potential of self-driving cars, you can go big or go home, and in the case of Audi that means it's racing time. This track day is unlike any other I've been on, simply because this is the first time in history where I or any automotive journalist has had the opportunity to take a hot lap inside what Audi calls a "piloted driving" vehicle or, to the rest of the world, an autonomous car. Taking autopilot smarts to a level never done before, Audi modified two RS 7 sedans with race car driver-like levels of intelligence, and then challenged me to beat them in a hot lap.

Meet AJ and Bobby, both named after high-achieving race car drivers – A.J. Foyt and Bobby Unser. I got to spend quality time inside and out with AJ, while Bobby was on the sidelines resting up for this weekend's big lap around Hockenheimring during the final races of the German DTM series, in front of thousands of spectators.

I had two objectives going into this once-in-a-lifetime event. First, I wanted to drive faster than Audi's self-driving RS 7 concept car around the track. Second (and maybe a little more important), I wanted to walk away without a scratch having called shotgun in the autonomous racer.

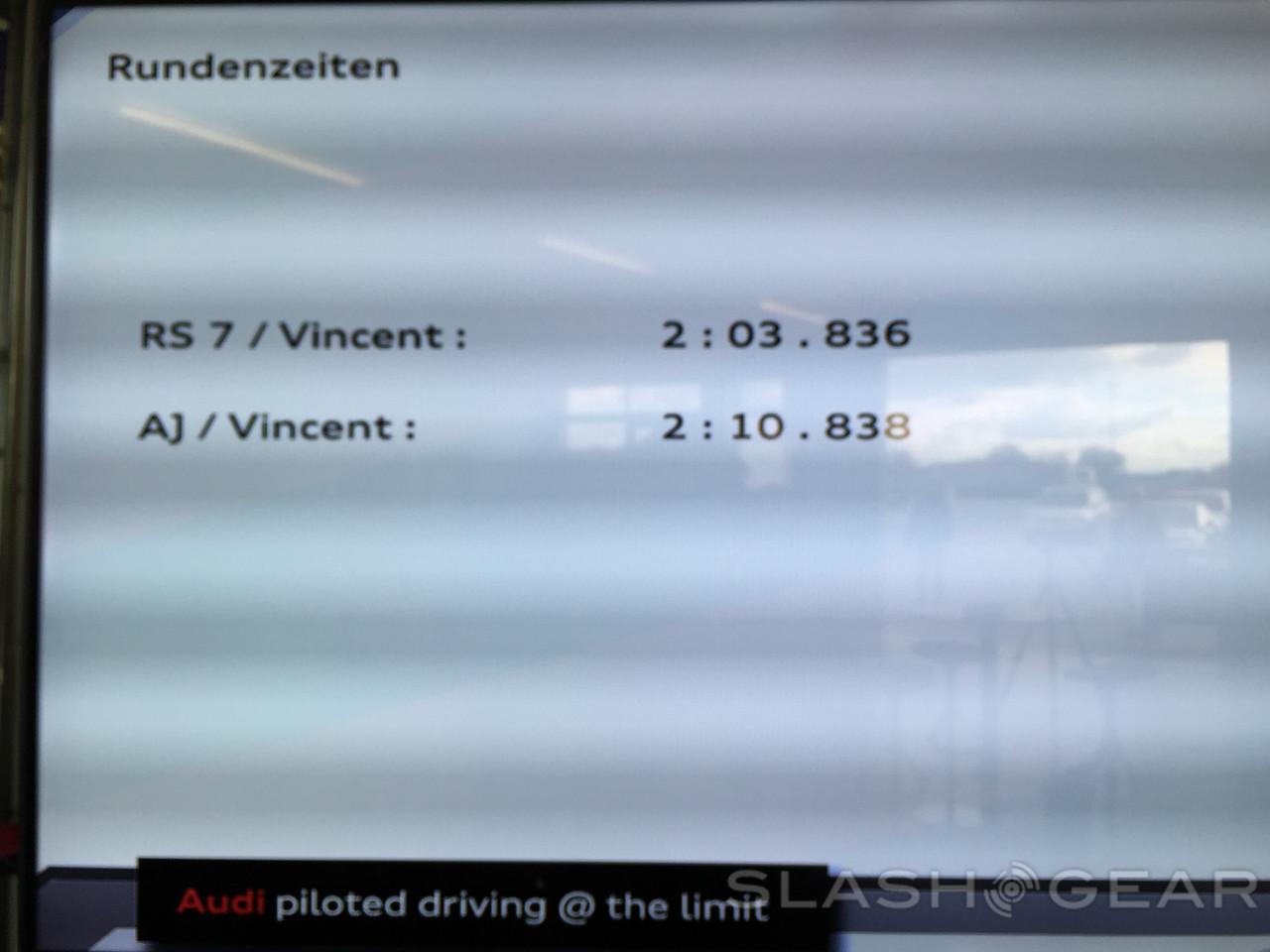

Let me touch on these two objectives before getting into the specifics and details of how Audi has achieved something no other car manufacturer has been able to do. I'm proud to say that, in the race between man (that's me) and machine (AJ), I came out victorious beating out AJ by 7.002-seconds.

So, you're wondering how in the world did an amateur auto journalist come out victorious against the mighty self-driving RS 7? The short answer is that Audi gave me an artificial edge, limiting AJ's performance due to the somewhat wet conditions of the track. In fact, AJ was dialed down to roughly 86% of his peak performance.

That's not to say I had familiarity on my side, though. I had one lap following the pace car, then another by myself, and then the third lap was where my time was recorded at 2:03.836. Once I finished that timed lap, I hoped into AJ for the hot lap where it finished with a time of 2:10.838.

At no time did I feel unsafe while riding shotgun, as AJ zoomed around Motorsport Arena Oschersleben. That day, Audi later told me, the self-driving car hit 201.5 km/h (125 mph). The cars did even better at Hockenheimring, hitting 240 km/h (149 mph).

It didn't quite sit right with me that AJ had lost, so I patiently waited until the very end of the day where I got to ride in the back seat with another journalist. The track was much, much drier at 5PM then it was at 10AM that morning, so this time around AJ's performance limiter was dialed to 93%.

So how'd he do? In fact, the autonomous car gained an astonishing 9.166-seconds with a lap time of 2:01.672! Still, to keep things in perspective, if I'd had the opportunity to drive once more my own time would have possibly been shorter, considering the track was by then pretty dry.

"Bobby is a car with a soul," Dr. Horst Glaser, Head of Development Chassis, told me about Audi's piloted driving project, "because he knows the track and he knows to ride the track, and that's what we trained him. He's full of intelligence."

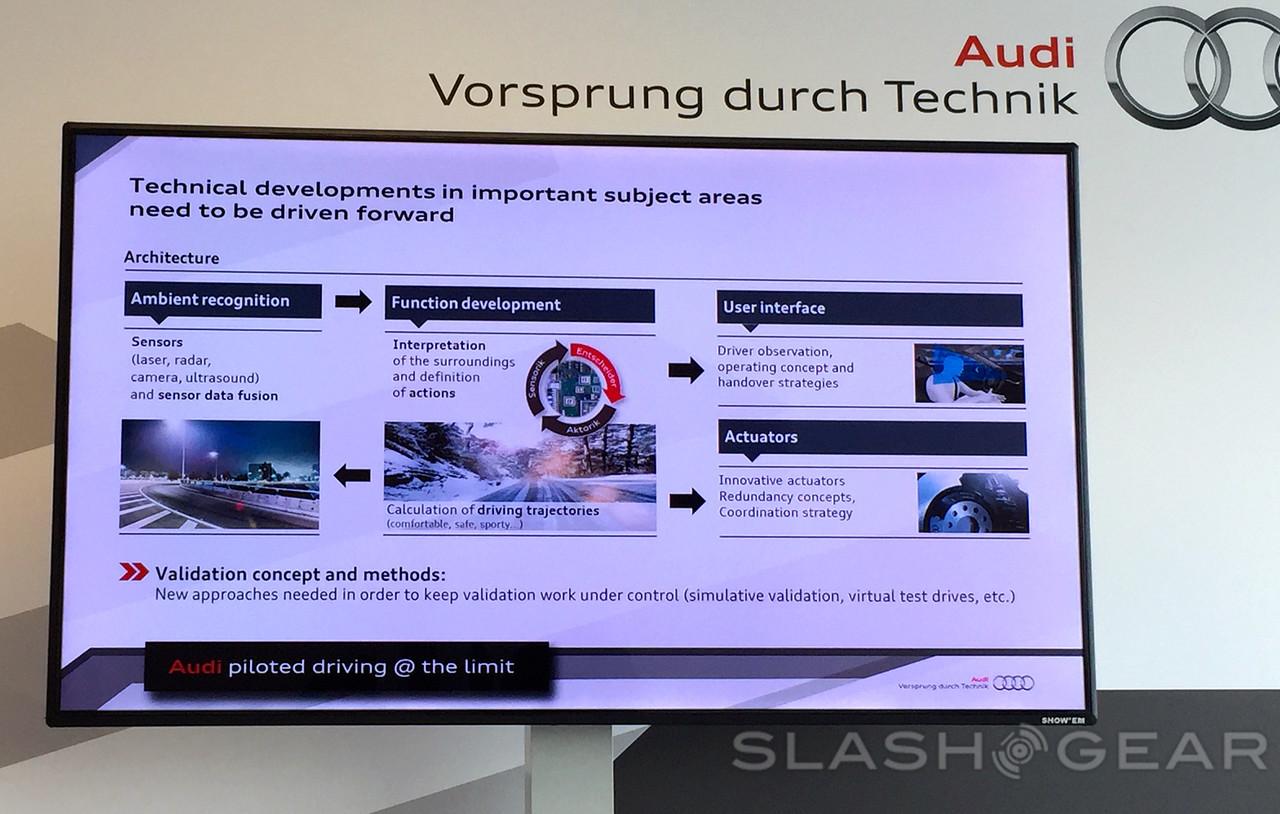

Whether you call it soul, intelligence, or a brain, it's what takes a 560 HP car capable of 189.5 mph and gives it the abilities of a race car driver, only without the human tendency toward fatigue. Bobby and AJ have been trained to drive the track, yes, but they also carry some highly-capable on-the-fly computation skills for assessing and mitigating unforeseen dangers.

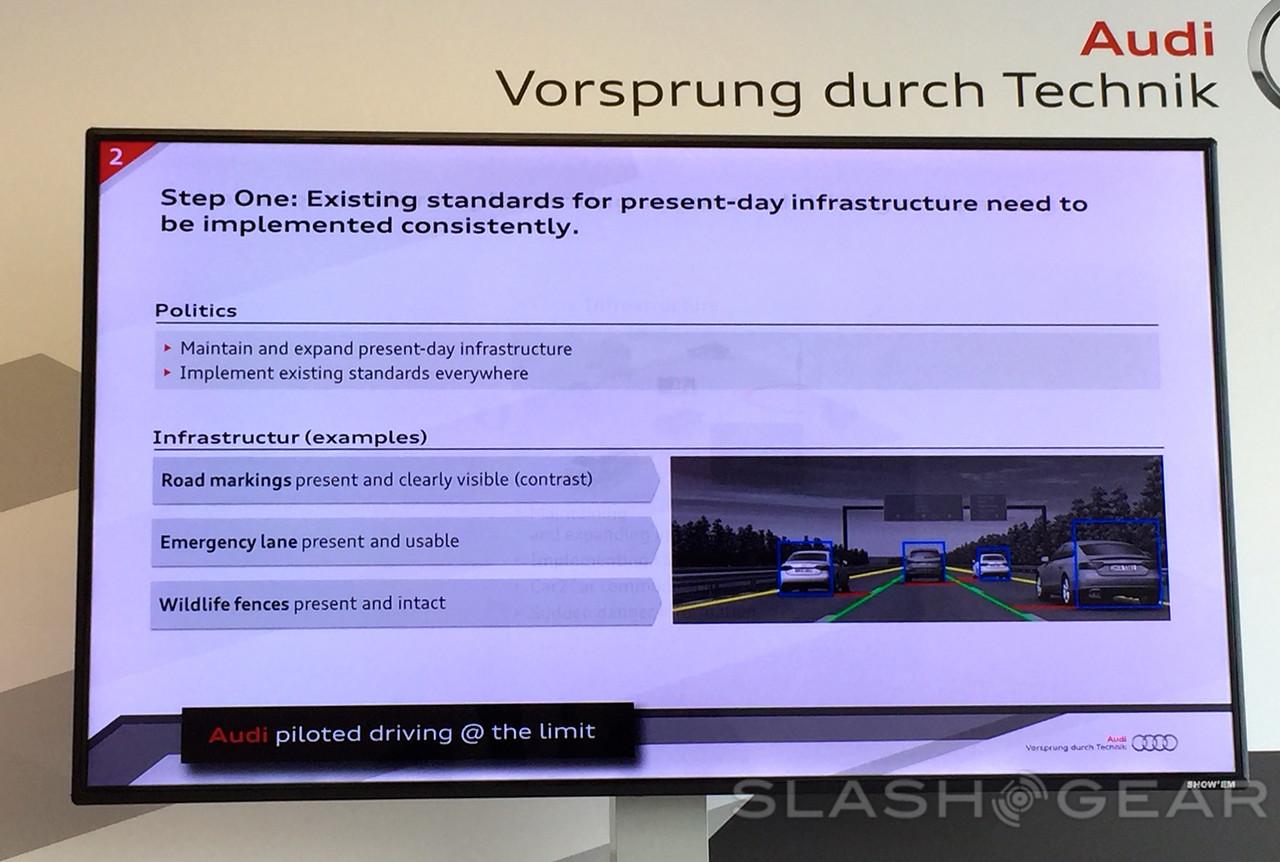

What makes Bobby intelligent relative to his peers on the road? As we've seen on other autonomous projects, it's a combination of camera systems, GPS, and differential GPS to track his precise location on the track, down to within 1 to 2 centimeters. Bobby knows the "ideal" lines, and he tries to follow them as best he can, each and every lap.

Bobby's "eyes" are a pair of stereo cameras, constantly taking images in order to compare picture by picture the track against the images stored on the onboard computer. At any given moment, Bobby is exactly aware of where he is and where he should be. For instance, if a situation arises where the car starts to oversteer and miss the proper line, it will know to make corrections.

The topic of oversteer leads to a good example of the difference between a human driver and an autonomous one. As you can see in the side-by-side comparison video, I completely screwed up the first turn by understeering, underestimating the weight of the RS 7. Because the Audi is a much heavier car, I should've either started braking earlier, or braking harder, during the straight line before actually entering the turn.

Even though this mistake cost me around 2-seconds added to my timed lap, I still managed to recover and be on my way. In Bobby's case, however, he wouldn't have made this human error in the first place (as you can see from the video). Even in more unpredictable circumstances – like the track being wet, causing the car to fishtail – Bobby will know to instantly react and correct a slide, just like an experienced human counterpart would.

Audi compares its system to the autopilot on a modern airplane, and that includes redundant safety measures. There's more than one system used for localization, for instance: after all, the car needs to know exactly where it is at any given moment on the race track, combining the inputs of dual cameras mounted on the driver's side and differential GPS.

Other redundancies are found in the braking system – if one braking system fails, the other kicks in – and the same for signal areas, with multiple sensor arrays included. The third key redundancy is the power supply, ensuring that, if something fails, the second system takes over. Each of the redundancies compare results, to make sure they match up for the most optimal performance.

The sum of those parts is what Audi says will be the best piloted driving experience available in the very near future. According to Dr. Glaser, limited "piloted driving" is two to three years away, and the first two Audi models with such features will be the next-generation of Q7 SUV and A8 luxury sedan. For instance, the A8 will be endowed with assistance driving: during traffic jams under speeds of 60km/hr (37mph), the driver will be able to turn responsibility over to the car, so that they can sit back and relax.

"We can defuse traffic situations," Dr. Glaser explained of Audi's ambitions.

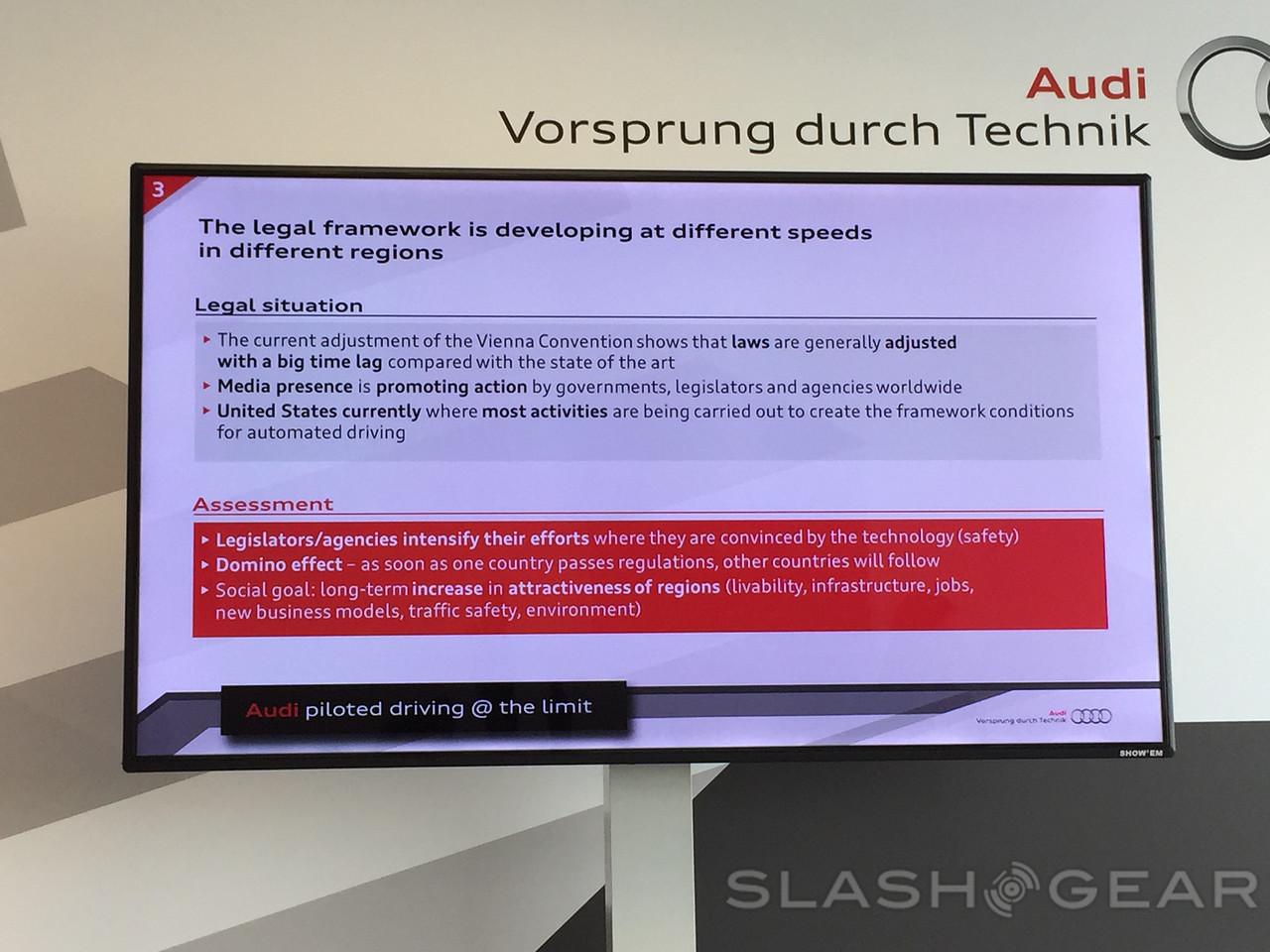

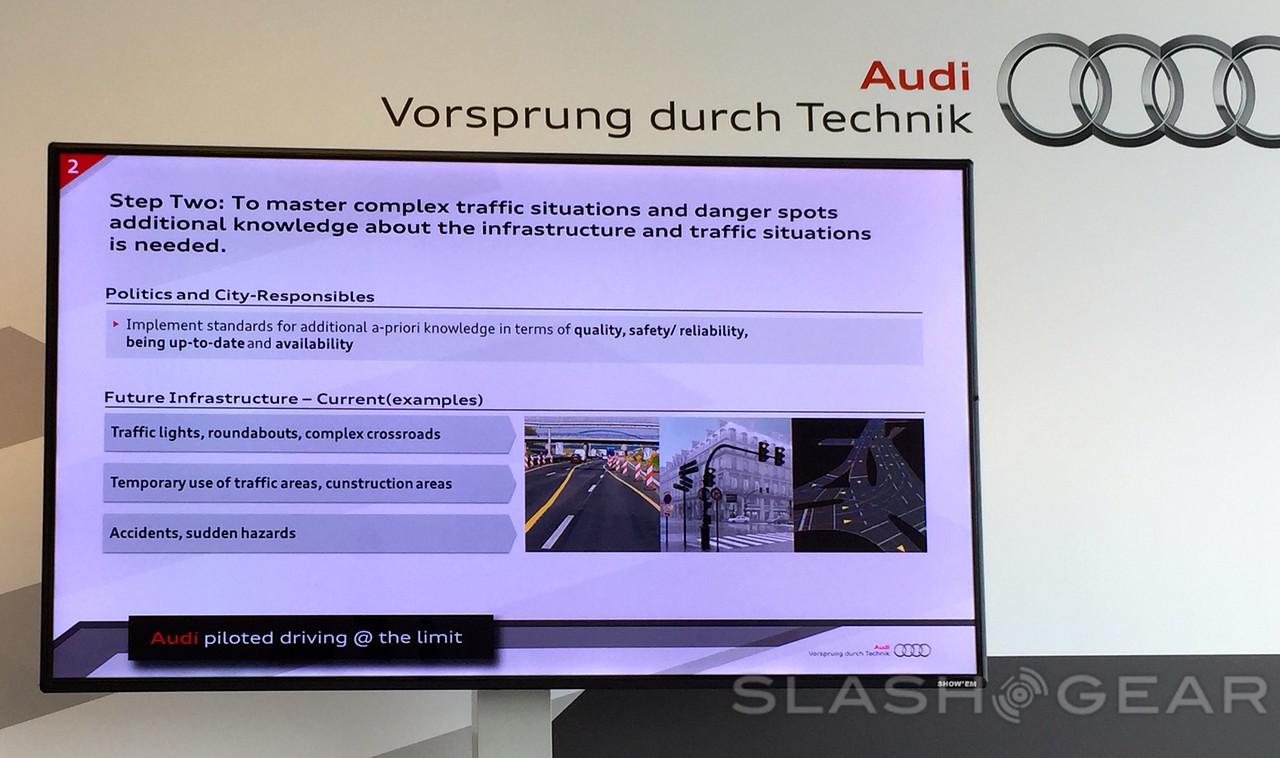

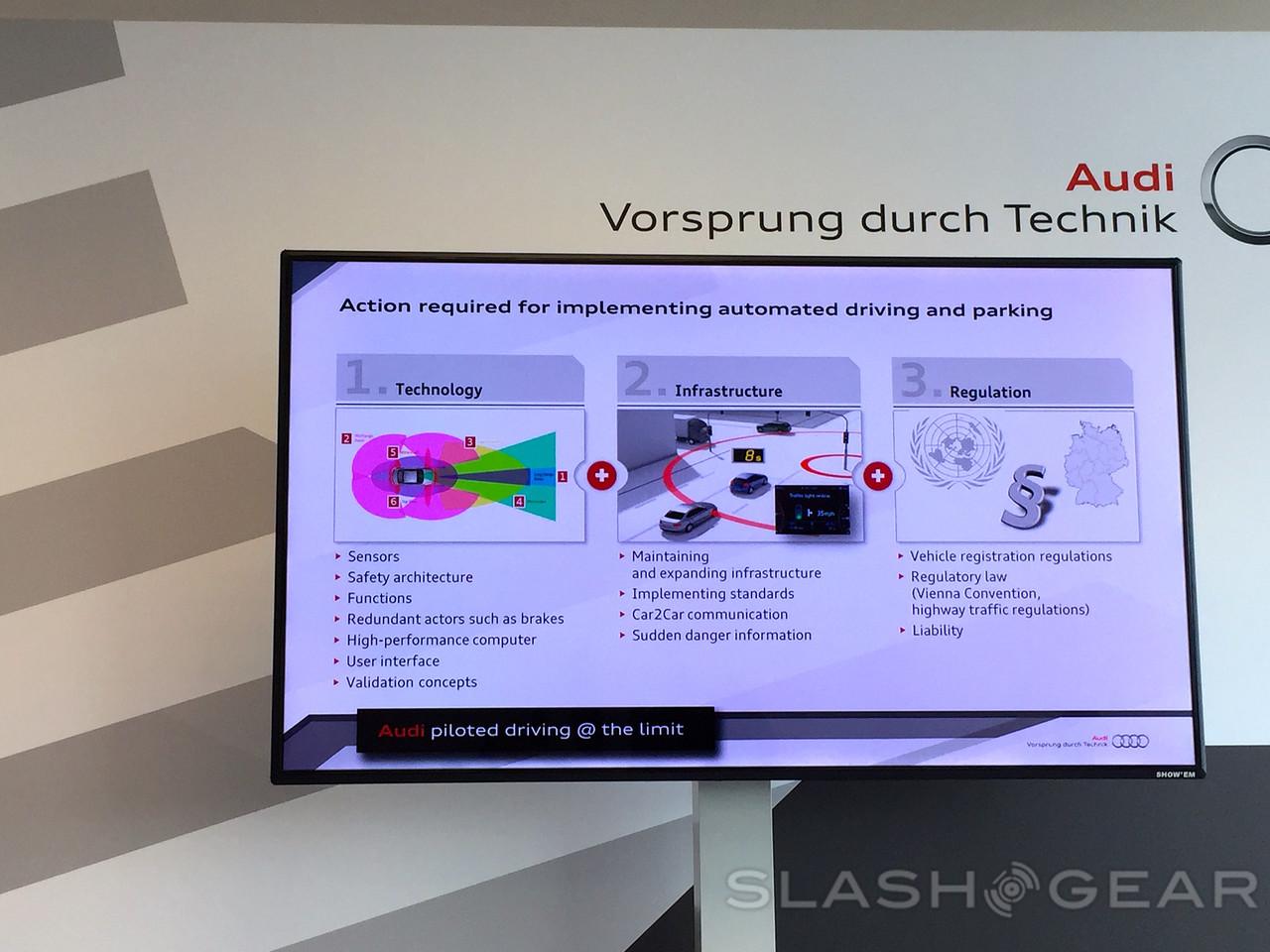

We're still some way from fully autonomous cars: the Audi you can summon from the garage using your phone, then sleep in the back seat as it takes you to work, automatically parking itself when you get there. The combination of pre-learning – the precise map of the track AJ and Bobby each have – with real-time tracking means a self-driving car would need a huge degree of understanding about every road, every highway, and every junction before it was safe to let loose entirely unrestricted.

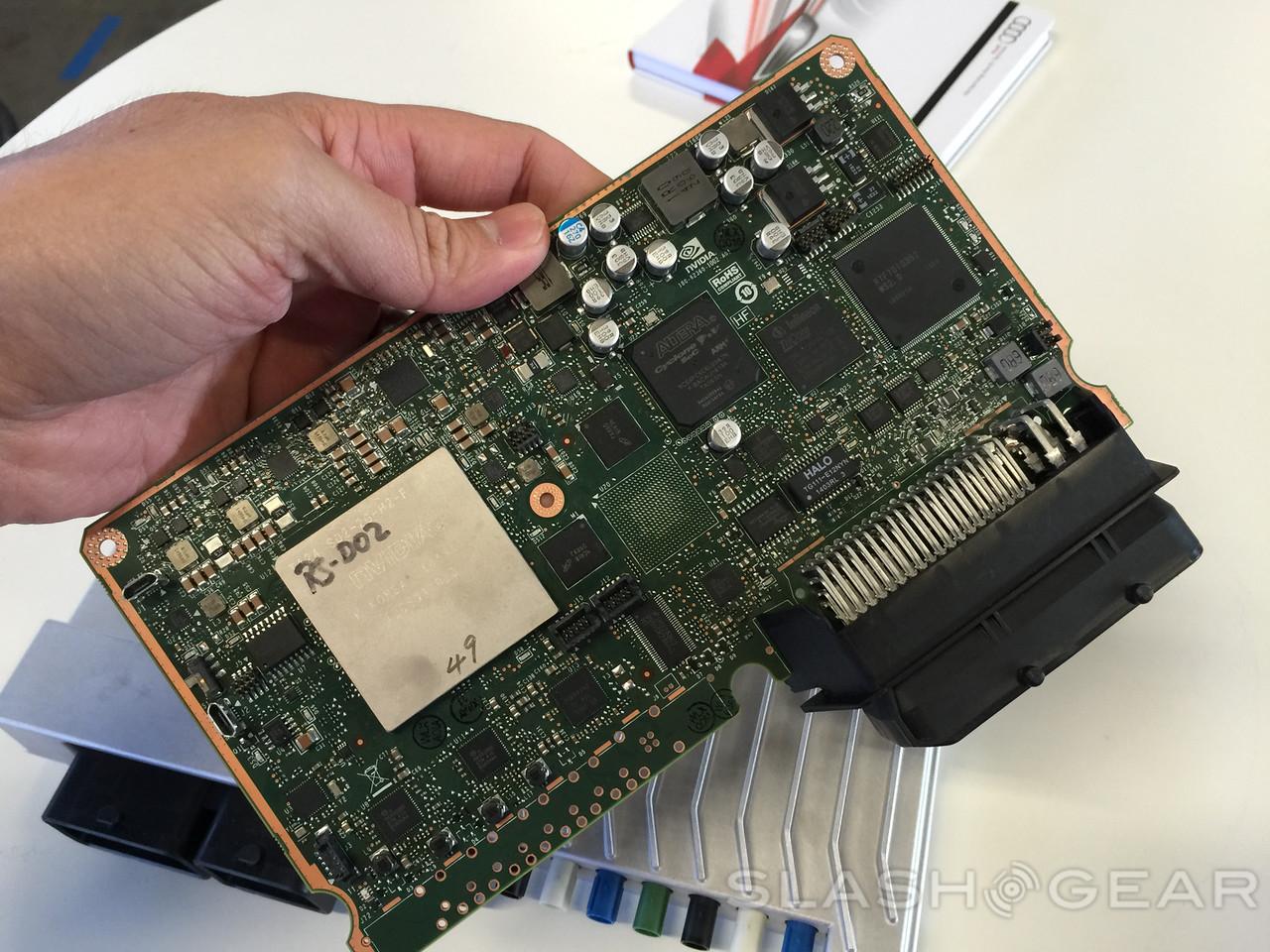

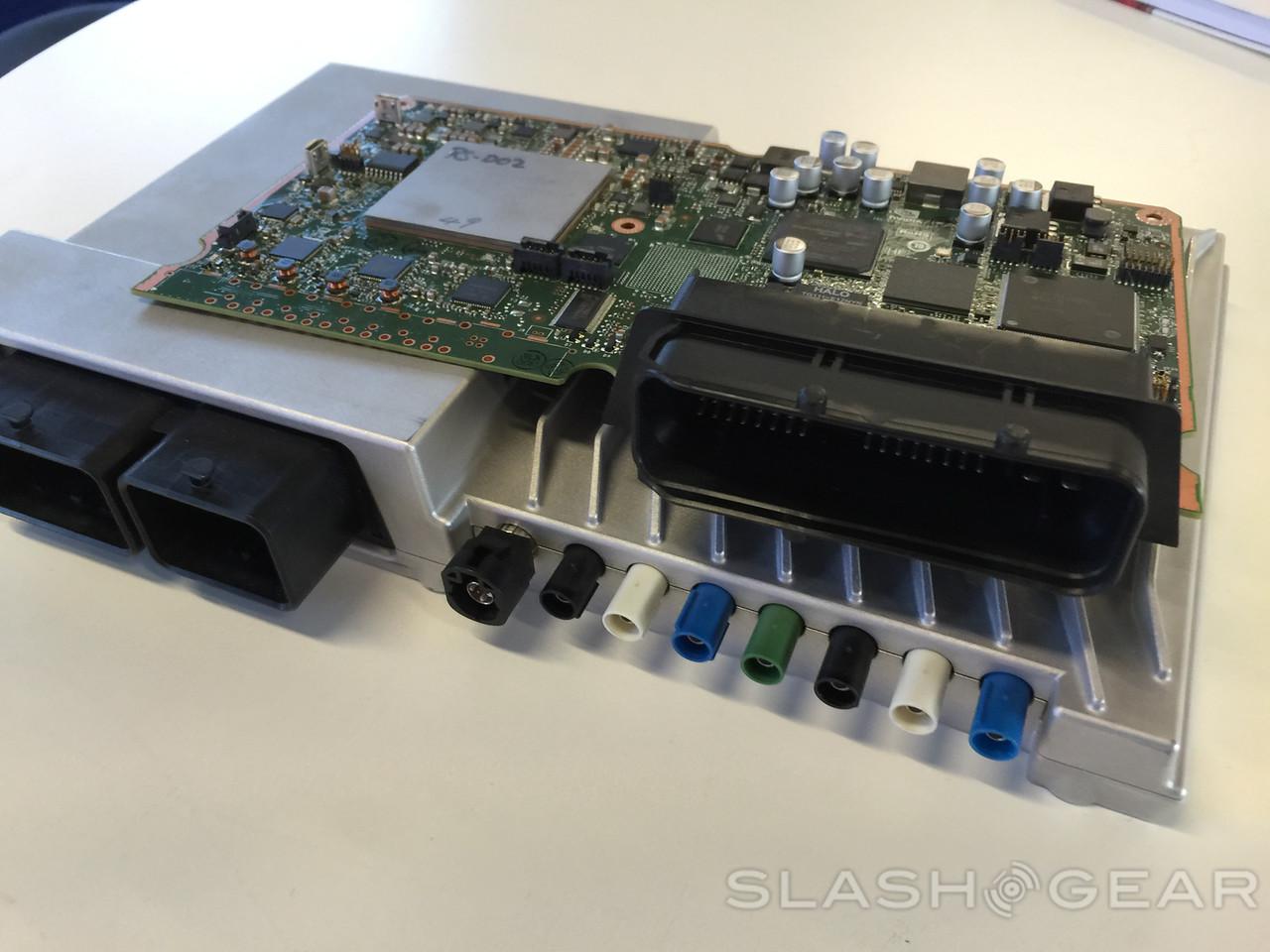

Nonetheless, the technology is there, even if the detailed digital maps of the world (not to mention the regulatory nuances) aren't quite ready. Bobby and AJ prove you can fit an autonomous driving brain into a single Tegra-powered computer roughly the size of a shoebox: it takes up only a little more space in the trunk than the regular MMI infotainment system, in fact.

For the moment, in the battle between man and machine, I walked away holding the first-place medal. Give them a few years, though, and a richer database of the world around their sensors, and Bobby and AJ's descendants will more than likely flip that on its head. And as I sat in traffic on the way back to the airport, watching human drivers on either side struggle to stay focused on the crawling cars around them, I decided piloted driving with the smarts of an RS 7 racer can't come too soon.