Framework Laptop Promises Easy Upgrades And Modular Ports

A new laptop startup aims to make a DIY, upgrade-friendly notebook, with Framework hoping to build a market from those frustrated by today's breed of sealed-up computers. Combining readily-accessed internal components with modular, interchangeable expansion cards, the Framework Laptop may look like a regular 13.5-inch notebook but it's very different inside and out.

"At Framework, we believe the time has come for consumer electronics products that are designed to last," Nirav Patel, company founder, says of the startup. "Founded in San Francisco in 2019, our mission is to empower you with great products you can easily customize, upgrade, and repair, increasing longevity and reducing e-waste in the process."

The company's first product marks a return to some of the traditional approaches to notebooks, blended with some newer ideas. The Framework Laptop has a 13.5-inch 3:2 aspect screen running at 2256 x 1502 resolution, a milled aluminum housing that's 15.85mm thick and 2.87 pounds, and runs 11th Gen Intel Core processors.

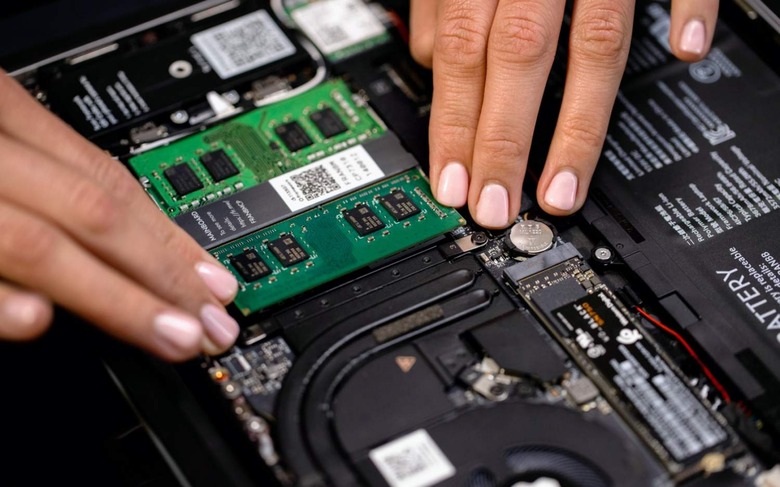

It'll support up to 64GB of DDR memory and 4TB+ of Gen4 NVMe solid-state storage. There's also a 1080p/60fps webcam with a hardware privacy switch, a 55 Wh battery, and a keyboard with 1.5mm travel. However it's how those components are pieced together that stands out.

The storage, WiFi card, and two of the memory slots are socketed, so that they can be upgraded by an individual user. The mainboard itself is designed to be swapped out too, as processors improve. The battery, screen, keyboard, and even the magnetically-attached bezel are designed to be readily replaced. Framework will even have QR codes on each component which, when scanned, will link to replacement guides and product listings.

Meanwhile, for connectivity there'll be four swappable bays for Framework's Expansion Card system. It'll have a choice of USB-C, USB-A, HDMI, DisplayPort, and MicroSD port modules that can be slotted in, as well as less common options like extra storage or even a high-end headphone amp. The company plans to open up the design for that, too, so that other companies can make compatible modules.

It's fair to say that Framework faces an uphill battle. Modular devices haven't exactly had an easy go of things in the past, with even big names in the tech world giving up on their plans. Google's Ara modular phone, for example, was meant to be as easily-upgraded as a set of LEGO bricks: instead, Google canned the project.

Intel, meanwhile, had plans for a modular laptop design. Its Compute Card would effectively condense the key components into a single block, which could be slotted into a notebook casing. It shelved that idea back in 2019.

The fact that the computing segment has been so aggressively commercialized explains part of the challenge. Low-price notebooks have relied on manufacturer scale to squeeze supplier costs down to the bare minimum; meanwhile, sleeker ultraportables and performance laptops demand custom designs in order to satisfy user requirements for both power and portability. That has led to little to no support for user-upgradable parts like memory or storage, since RAM chips and flash drives are soldered in place to save on thickness.

Framework's approach differs dramatically from that. In fact, as well as prebuilt models running Windows 10 Home or Pro, it'll also have a Framework Laptop DIY Edition. That will come as the individual components, and the choice to load either Windows or Linux if you'd prefer.

The Framework Laptop itself uses 50-percent post consumer recycled (PCR) aluminum, and an average of 30-percent PCR plastic.

What we don't know – and what a lot of this will hinge upon – is pricing. Exact specifications, costs, and preorder details will follow closer to Framework's summer 2021 estimate for the laptop shipping, the company promises. It's difficult to imagine that there won't be some premium to pay for this degree of flexibility, never mind the fact that smaller laptop-makers typically end up paying more for components than their industry heavyweight rivals.