Apple M1 MacBook Air Review (2020) - Evolutionary Leap

- Apple M1 is astonishingly fast

- Excellent battery life

- Compatibility with non-native apps is impressive

- 720p webcam is still underwhelming

- Lack of an embedded 4G/5G option is frustrating

Were Charles Darwin here today, once he'd finished screaming at us for tinkering with necromancy and demanding to know what the heck a Lexus was, I think he'd want to see the new MacBook Air. Apple's M1-powered notebook is one of a trio of Apple Silicon showcases and, as the "Father of Evolution" was well aware, some generations take a leap forward, not just a step.

Though at $999 the M1 MacBook Air isn't the cheapest model to use Apple's homegrown chipset – the new Mac mini starts at $699, albeit before you budget for a display and peripherals – it's arguably the purist example of Cupertino's strategy. Fanless and self-contained, it promises a beguiling combination of flexible performance and battery life, wrapped up in a familiar design.

The aesthetic explains how Apple could bring its first Apple Silicon models to market so rapidly, since it didn't need to retool for new laptop or desktop chassis. In fact you'll need to slap an "M1 Inside" sticker on the lid if you want people to know you're at the cutting-edge. Some of the function key labels are tweaked versus the Intel-powered Air, but otherwise this is the same ultraportable we've known for a few years now.

That means a 13.3-inch 2560 x 1600 Retina display, a full-sized Magic Keyboard, Touch ID built into the power button, a sizable trackpad, and a 720p FaceTime HD camera above the screen. The port selection remains as controversial as ever, with two Thunderbolt 3 on the left side (that also work as USB 4 Type-C), and a 3.5mm headphone jack on the right. While I agree that two ports on a MacBook Pro seems miserly, I think the selection is just about acceptable on the slimmer MacBook Air.

Inside, 8GB or 16GB of memory, between 256GB and 2TB of SSD storage, and both WiFi 6 802.11ax and Bluetooth 5.0 wireless can be found. Star of the show is the Apple M1, of course, though the specifications differ very slightly depending on which MacBook Air configuration you buy.

The entry-level $999 machine with 8GB of memory – the one I'm reviewing – uses an M1 variant with an 8-core CPU, a 7-core GPU, and a 16-core Neural Engine. The $1,249 version of the Air, however, has an M1 variant with an 8-core GPU. Both, though, are capable of driving up to a single 6K 60Hz external display (at least, officially).

As anybody following the Apple Silicon story likely already knows, the headline here is Apple using for its Macs the same chip tech that powers its iPhone and iPad models. That combination of Arm-based hardware – versus Intel's x86 processors – and software like macOS Big Sur allows for the same sort of optimizations on Mac that have long made iOS and iPadOS such powerhouse platforms. It also helps narrow the gap between those three ecosystems, computer and tablet and phone, by supporting native iOS/iPadOS apps on macOS for the first time.

The flip side to that is compatibility with the apps Mac owners have already been using. It's a problem that has stymied attempts by Microsoft and Qualcomm to coax Windows on Arm into making any sort of splash: getting all the pieces of apps, operating system, laptop, and the core chipset to line up properly has turned out to be akin to herding cats. Apple's solution – in somewhat typical Cupertino fashion – is a mixture of stick and carrot.

On the one hand, the transition is inevitable. Apple may still have Intel-powered Macs coexisting alongside their Apple Silicon counterparts for a while to come, but the writing is undoubtedly on the wall for them. Developers are under no misconception about the future of the platform.

To make it less arduous a change are things like Rosetta 2. In short, while native software written for Apple Silicon is best, Rosetta 2 allows apps written for Intel-based Macs to run on the new M1 and future Apple-designed chipsets. In theory, it means the same programs you're used to running on your old Mac should work on your new MacBook Air. Indeed, Apple says you could even notice an uptick in speed.

I suspect most software the typical MacBook Air user requires will run just fine. Apple's own apps are, you'll be unsurprised to hear, ready for the M1: if you use Pages, Numbers, and Keynote for your productivity; Mail for your email; iMovie for your videos; and Safari for your browsing, you're good to go out of the box. Even more complex apps, like Final Cut Pro, along with some third-party heavyweights like Microsoft Office 365 and Google Chrome, now have Apple Silicon versions, at least in public beta.

It's not a clean sweep, though, despite what Apple suggests. The closer to edge-cases you get, the more likely you are to run into issues with compatibility. Parallels users, for example, won't be able to use that software to run Windows; if you're a VMWare Fusion user, you'll find it doesn't play properly with Rosetta 2 virtualization either.

Much as with the port selection, I feel like the majority of MacBook Air owners won't run into these sort of problems. There are handy third-party sites keeping check of what apps are running smoothly and which are not, so it's worth checking if there's a must-have title you can't live without. The reality, though, is that software developers want access to Mac users, and that's going to fuel the transition whether they're happy about it or not.

The other big concern some have voiced is memory. None of Apple's M1-based Macs can be configured with more than 16GB of RAM at the moment, which on paper is a compromise versus the 32GB+ that some Intel models can be equipped with. Thing is, it just isn't quite an apples to apples comparison.

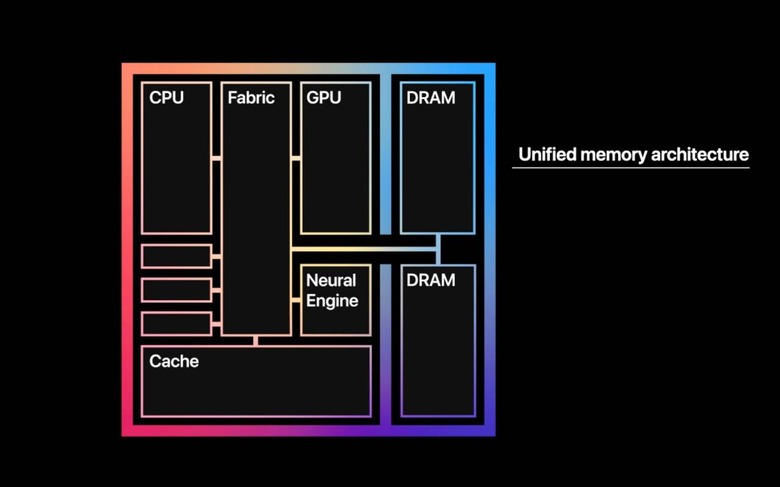

This new MacBook Air uses what Apple refers to as "unified memory" and, at its most fundamental, it means the memory is physically integrated into the M1 chipset itself. Intel-based Macs – even those with permanently soldered RAM chips – have separate slots. It allows all parts of the M1, whether processor, graphics, or Neural Engine, to tap into that same shared memory pool.

It adds flexibility, but it also pays dividends on speed. Rather than having to copy something from CPU memory to GPU memory, when the graphics chip wants to work on something the processor was handling, all of the M1's cores can address the same data in that shared memory.

Now, even with those advantages, that's not to say you can't run out of memory (at which point macOS Big Sur offloads to the slower SSD, as usual). What has proved a huge surprise, though, is just how difficult that is to do in day to day use.

I'm not a conservative memory-user. In fact you could argue I'm positively profligate: in a typical day I run Safari and Chrome simultaneously, each with at least a couple of windows open, and with 6+ tabs loaded in each of those windows. Then there's Apple Mail, and the messaging app the SlashGear team uses, and Affinity Photo for image editing, and usually a dozen or so TextEdit windows along with iMessage. Periodically I'll load up Final Cut Pro X, too.

My everyday machine is a 16-inch MacBook Pro with 32GB of memory and a Core i9 processor, and sometimes it's just not a happy bunny. Chrome is a notorious memory-hog, sure, but at some point there's only so much grunt to go around.

The degree to which the M1 MacBook Air has handled my uncompromising day-to-day use has been, frankly, astonishing. Things were made a little easier because most of my go-to apps are M1 optimized – if I was, say, an Adobe Lightroom user than I'd be reliant on Rosetta 2 emulation, which would be less efficient – but I could still run everything my usual MacBook Pro deals with and not encounter issues on the M1 MacBook Air. If benchmark numbers are your thing, we have those too.

Weirdly, the biggest disappointment has been iOS apps. Yes, they run – each in a separate window – but most are built for touch. You can use keyboard and trackpad to interact with them, but it's definitely a sub-par experience; it's hard to imagine Apple not bringing out a touchscreen Apple Silicon Mac somewhere down the line.

All the same, while it might not be perfect, there are times when an iOS app hits the spot. My colleague Vincent, for example, has been using an M1 MacBook Pro, and can now load the iOS-only app for his 360-degree camera on his laptop. My connected smoker doesn't offer a Mac app, but since I can now run the iPhone app in Big Sur, I can monitor my pork butt and tweak temperatures without having to pull out my phone.

The other advantage is battery life. Apple quotes up to 15 hours of wireless web-browsing from the M1 MacBook Air's 49.9 Wh battery, but I've been (metaphorically) burned so often by over-promising laptop estimates that I immediately dismissed that. Turns out, I shouldn't have been so pessimistic: by the end of a nine hour work day, macOS was typically telling me I still had around 40-percent battery left.

Again, your go-to apps will make a difference there: the more heavy-lifting Rosetta 2 has to do, the bigger the hit on battery life. The MacBook Air is fanless, too, which has its own pros and cons. I love the silent running, but beefy tasks inevitably involve more heat, and after a while the M1 will throttle back for reasons of self-preservation. Although I've been impressed with Final Cut Pro performance, for instance, those looking to Apple Silicon with video editing at the top of their to-do list should probably go for the M1 versions of the MacBook Pro or Mac mini, which have fans and thus can sustain their peak performance longer.

I called the new MacBook Air an example of tech evolution at its clearest, and sometimes that's not so much a standout feature as it is a general feeling when you live with a machine. It's about how rapidly the notebook wakes when you lift the lid – so quick, I had a moment of "is the light in the fridge on when you close the door?" style skepticism, and wondered if the MacBook Air simply wasn't sleeping at all – and how silky-smooth the animations are. At times it feels more like an iPad Pro that way, responsive and elegant.

Not perfect, though. The webcam may tap the Neural Engine to try to coax better quality out of its 720p sensor, but there's only so much you can do with software and it's underwhelming overall. It's frustrating that, while you can get an iPad with built-in cellular connectivity, you still can't get a MacBook Air with 4G or 5G onboard. And we'll have to wait to see what new form-factors – or even just a touchscreen – Apple has in mind.

Nonetheless, it's dramatic just how good this first-generation outing for Apple Silicon is. I usually wouldn't recommend being an early-adopter when it comes to big, evolutionary changes in platform like this switch away from Intel is, and yet Apple seems to have avoided not only the obvious pitfalls but the nuances as well. That I could move from an old Mac to this new MacBook Air and have the biggest takeaway be just how much nicer the experience was speaks volumes.

"The forms which stand in closest competition with those undergoing modification and improvement will naturally suffer most," Darwin wrote in The Origin of Species and, while I suspect he wasn't talking about PC versus Mac, the sentiment is no less true today. We may only be at the beginning of the Apple Silicon transition, but even this base-spec M1 MacBook Air proves that Windows notebooks must recognize that natural selection here isn't balanced in their favor.