Wild Technology Spies Have Actually Used

The world of espionage is filled with secrets, lies, and concealments. Secrecy and deception are inherent to the nature of the work. But this is nothing new. The history of warfare is rife with secret assassins and undercover spies with stories as old as the Bible, laying out acts of espionage by concealing one's identity. As technology advanced, especially after the Industrial Revolution, the invention of spycraft also advanced. Overcoming new technologies has necessitated ever-increasing clever means of deception, and the Cold War gave us perhaps the most ingenious of methods to gather intelligence and pass along information.

When talking about state-sponsored espionage, acronyms of various states play a role. The CIA in the United States, KGB in the Soviet Union, HVA of East Germany, and MI6 from the United Kingdom. These agencies, and more, are forever conducting clandestine missions to gain an advantage over their adversaries. Seemingly unlimited budgets go into research and development that allow some of the most clever and intelligent minds to work toward creating inventions to outsmart the other side. While the gadgets of James Bond can seem silly and impractical, the real spycraft used in the field may not be far off from being separated from fiction. Looking through the history of espionage can be a fascinating journey. Here are 10 wild technologies spies have actually used.

American Official Seal Decoration

The peace in Europe after WWII gave rise to a tense time of international relations among former allies. While the Soviet Union and United States worked together to defeat the Nazis, the relationship went cold quickly after hostilities ended. However, the two countries held diplomatic relationships continuously throughout the period, with ambassadors and diplomatic concerns in each other's capitols. This presented many opportunities for spying, and the Soviets managed to make a play for information that was among the largest breaches of national security from the whole period.

In 1945, as the war was drawing to its conclusion, Russian school children arrived at the home of the American ambassador in Moscow bearing gifts. Among them was a large carved seal of the United States. Being thankful for the gesture, the ambassador hung it on the wall behind his desk, where it remained for seven years. Unknown to the Americans was that the seal contained a device that allowed to Soviets to hear every word spoken in that office without the use of electricity or transmitters. What came to be known as "The Thing" was a hidden listening device that consisted of a small membrane connected to a quarter-wavelength antenna. The proper frequency radio wave could be transmitted toward the device, sending back a signal allowing every conversation to come through with astounding clarity (via Mental Floss).

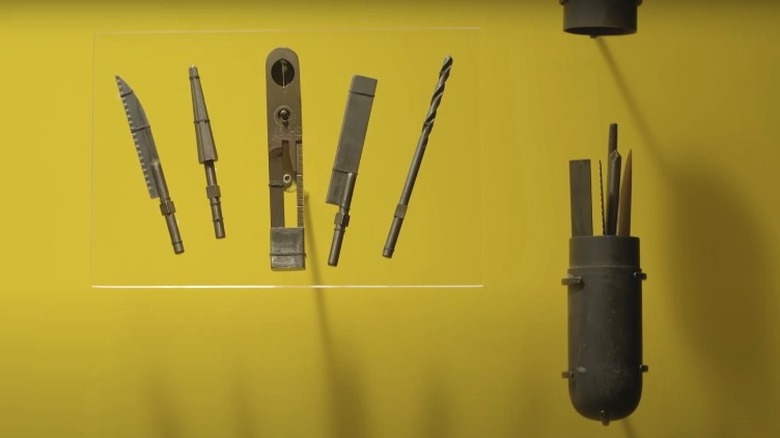

CIA Toolkits

Anywhere a spy goes, preparedness for any situation is paramount. They have to carry an array of devices and tools to complete whatever mission is before them. Sometimes, this takes the form of traditional tools such as screwdrivers, files, or pint-sized drills. They can be used for installing bugs, or to escape capture. Often, these spies are traveling under assumed identities, and must pass through customs and border checks like any average citizen. Drills and files might draw suspicion to an eagle-eyed East German border guard. Therefore, the CIA had the toolkit.

Encased in housing that resembles a large medicine capsule, the toolkit contained a small selection of knives, saws, files, and drill bits, along with an interchangeable handle. To keep from drawing attention, the kit would be inserted into the most private and secure place possible on, or rather in, the human body (via Spy Museum). It is rather uncomfortable to consider the depths that agents had to go through to complete their mission at times, but it is all in service to national security. I supposed we should all be thankful.

Cigarette Pack Camera

Smoking used to not be such a taboo, and there was a time when nearly half of all adults smoked. For spies, this gave ample opportunities to hide their tools within ordinary cigarette packs. During the height of the Cold War, nobody would think twice about anyone carrying a pack of Lucky Strikes. The U.S. Army originally developed a camera hidden in this manner in 1949.

This little camera was rather inventive for its time. It was housed in an actual package from Lucky Strike, while a light meter was concealed in a carton of matches. To be fair, it never made it past the prototype stage, but it was actually produced and fully functional. The tiny camera consisted of a four-speed shutter, four-position aperture, and Sonnar-type lens of good quality. It was capable of taking 18 photos on 16mm film, according to The Drive.

This camera set still exists today. Only a couple of prototypes were made, making a surviving example exceedingly rare. One set went up for auction in 2015. The auction was hosted by Bonham's, who listed the estimated value of $41,000 to $64,000. The final sale price was not published.

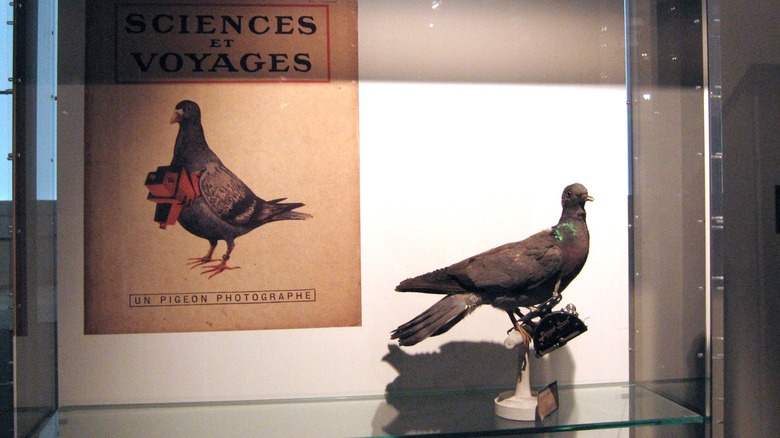

Pigeon Cameras

Pigeons have been domesticated and trained for use in communications for millennia. There are records from ancient Baghdad and Syria of pigeons used to transmit messages over great distances, according to historian Matthew McIntosh. Pigeons were raced in Brussels in 1818, and their use may have been the deciding factor at the Battle of Waterloo during the Napoleonic Wars. They have also been known to carry mail, such as with the Great Barrier Pigeon-Gram Service of Austalia in the late Victorian era. They continue to be used in remote parts of India during times of natural catastrophe.

During WWI, pigeons carried encrypted messages to and from commanders where it would be too dangerous for soldiers to go. They also used special cameras installed in a harness to take aerial photos for reconnaissance purposes. Reports from as early as 1908 detail operations of pigeon photography. The harness would activate the shutter from the movement of the birds, taking up to 200 photographs in quick succession with this bizarre camera setup. This could give commanders a broad view of the terrain in as close to real-time as possible.

Microdot Cameras

Using film with the right combination of lenses to make photos extraordinarily small, all to pass information indiscreetly, is a rather old idea. The Ultimate Spy by H. Keith Mellon says that micro photography's roots go back as far as the American Civil War, and have been used by just about every clandestine operation ever since. The KGB's mole in the CIA, Robert Thompson, used microdot to pass sensitive American information to the Soviets. Microdot photos are so named because they can condense an image onto a piece of film as small as a 1-millimeter square. They are highly concealable and easy to pass, looking like nothing but a speck of dust to the untrained eye.

The cameras used for microdots have been built by many manufacturers all over the world. Some of the smallest and most sophisticated come from the CIA. The Model MK VR microdot camera from the CIA in the late '40s was a clever device about the diameter of a quarter. It housed a film disc with 10 exposures, and was used by opening the cap on the lens, acting as the shutter, and rotating the lens to snap more photos on the remaining exposures, reducing the images as much as 200 times the original (via Stan Hope Microworks). The East German HVA intelligence service used another type of very small microdot camera with a roll of film that worked similar to old 110 film type cameras, only smaller. With the transformation of photography to digital formats, microdot film is obsolete, but tiny cameras are not.

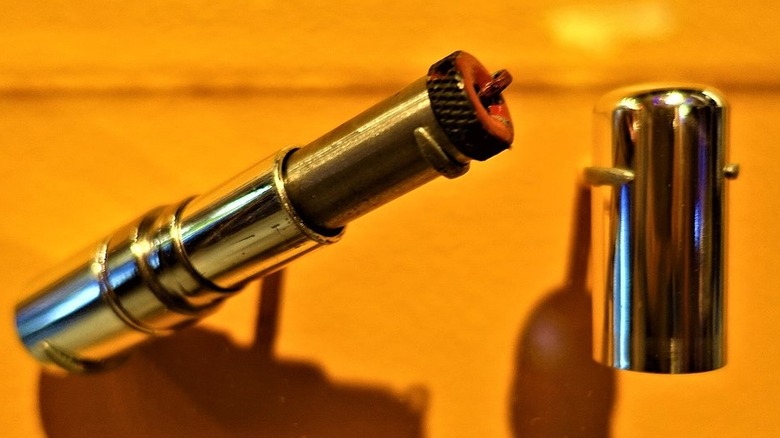

Lipstick Pistol

The use of women in the clandestine services was a shrewd choice on the part of the higher-ups, as women can often blend into a crowd and draw less attention, posing as housewives or professional support staff in government agencies. Women are also used in a role called "honey pots," in which they use sex appeal and seduction to infiltrate our government operations, often successfully. Anna Chapman, a Russian agent, successfully infiltrated the world of high finance in the U.S., and was arrested in 2010 along with nine other Russian agents.

The tools of the honey pots are often hidden in plain sight as the contents in a purse. The KGB managed to disguise a single-shot pistol as lipstick (via Joy of Museums). This is clever concealment, however, not a terribly effective weapon. One would assume it was meant to use only in close range, and as a last resort. The weapon was produced in 1965 and eventually discovered at an American checkpoint in West Berlin.

Stirn's Buttonhole Camera

By 1886, photography had already been around for about 60 years, so the technology had time to mature, and inventive people found ways of adapting it to specific purposes. One such camera with a clever design was Stirn's buttonhole camera. It was not a development specifically for military or government uses, but could still be used to take photos secretly. C.P. Stirn bought the rights to make the camera in 1886, first produced by Western Electric Co. of New York, and turned it into a commercial success, selling 15,000 units in two years (via Exibart Street).

The camera was a flat, round, and shallow cylinder that carried a disc of film with a small protruding lens. It was meant to be hung from the neck with the lens poking out through the buttonhole of a vest, which was common attire for men of the period. Advertisements of the time claimed it to be the only camera invisible to the eye, and it could take six pictures with the subjects being completely unaware. It may have been used as more of a novelty than a genuine tool for espionage, however, it is not unreasonable to assume some intrepid detective might use it to gather evidence of a crime.

Sheet Music

Josephine Baker was one of the 20th century's most enduring icons of music. She gained fame and fortune in the '20s, only to escape to France where she felt freedom in a way that she never could in the United States, even outside of the Jim Crow South. And it was France's embrace of her that led her to hold a strong devotion to her adopted country. Therefore, as the real danger of the Nazi regime grew in 1939, French counter-intelligence agency Deuxième Bureau sought to recruit her (via The New Yorker).

As the invasion of France commenced, Baker fled to a large villa in Vichy, France, and continued to collaborate with the grossly segmented and officially disbanded French intelligence agency. She then embarked upon a tour, traveling through Franco's Spain, and brought with her secret information to share with the British. Her star power gave her excellent cover as her trunks full of stage costumes and fine clothes passed through with barely a glance. All the while, notes written in invisible ink were scattered throughout her sheet music. Invisible ink is hardly a novel spy technology, but the way Baker used it is remarkable and ingenious. She eventually shared what information she could after arriving in Morocco. Her information gathering ended in Casablanca, as she fell ill and could not leave for around a year.

Insectothopter

The insectothopter was never actually used in the field, but it is just so interesting and ingenious, it is worth having a closer look. While the naming of it sounds a bit hokey, this is its official designation by the CIA. The agency says that it developed the insectothopter in the '70s as a way of transporting a listening device covertly disguised as a dragonfly. The initial plan was for a bumblebee, but the agency found that bee flight patterns were too erratic, so the dragonfly replaced it. It was driven by a tiny fluidic oscillator, and gained additional thrust from the expulsion of the gas from the motor. It relied on a laser in the rear for guidance, as well as relaying the listening device data. The agency has a video of it in action on its website and, while it did work, crosswinds could too easily throw it off course, and it was shelved.

While the CIA did create this tiny UAV, it never saw service. Interestingly, in the '90s, Russian intelligence attempted to make a copy. The Spy Museum's website shows several pictures of it. Clearly, the Russians copied the idea, but were less successful in its camouflage, as its look is distinctly mechanical, and constructed of clear acrylic and metal.

Charlie the Robot Fish

If anyone associates the name Charlie with any fish, it is likely the mascot for StarKist canned tuna. However, he's not the only Charlie to live beneath the waves. In the 1990s, while the development of UAV drones like the Predator was in full swing, the CIA was attempting to develop an unmanned underwater vehicle (UUV), a government activity that continues today, and it resembled a catfish. They named him Charlie because ... reasons.

Charlie was a UUV developed to collect water samples. According to the CIA, intelligence collection comes in all forms, and gathering info about the environment can be as useful as intelligence about the movements of people and machinery. That is why Charlie exists. Charlie and his doppelganger partner, a second unit built named Charlene, were controlled by a line-of-sight radio handset and contained a pressure hull, ballast system, communications system, and propulsion system in the tail. At 61 centimeters, Charlie would fit right into the average size range for catfish, and was hopefully unlikely to be mistaken for the real thing. The CIA could send one of the fish into a river and swim upstream, collecting data that could indicate the existence of nuclear waste runoff, as an example.

While the CIA never implemented Charlie or Charlene in service, research for this type of mission goes back decades. According to Boing Boing, the University of Washington developed SPURV, the Self-Propelled Underwater Research Vehicle, in the '50s. It was used by the U.S. Navy to take samples in the open ocean, and was retired in 1979.