Surprisingly Deadly Technology Throughout History

Technology, like just about anything else in existence, can be used for good or for ill. There's no arguing that technology and scientific discovery has improved the quality of human life overall. In general, human health and access to education have improved over time (via Vox) but every now and again, we make a terrible misstep.

Of course, there are plenty of technological innovations that are deadly by design. Weapons of war, for instance, cost countless lives and, while that's absolutely tragic, it isn't surprising. They're doing exactly what they were designed to do. Then there are the innovations that result in sneakier deaths.

We sometimes stumble upon some new information we don't wholly understand. In our fervor, we latch on, excited by the new possibilities, and open the door to a threat we're not even aware of. When that happens, we can inadvertently cause countless deaths and untold suffering before we even realize we've taken a wrong turn. Today, technology is advancing faster than ever, which could mean the potential for surprises is higher than it has ever been. These surprisingly deadly technologies from our past serve as a warning to tread more carefully as we move into the future.

Radium

Certain elements have been releasing radiation since nearly the beginning of time, but we didn't know that until relatively recently. In 1896, Henri Becquerel was studying X-rays when he stumbled upon the fact that uranium salts emit invisible radiation (via The Nobel Prize). That work inspired Marie Curie to study the phenomenon, resulting in the eventual discovery of radium. That work ultimately resulted in a Nobel Prize for Marie and Pierre Curie, which they shared with Becquerel.

Unfortunately, people didn't realize at the time that radiation was hazardous, and radium was subsequently used in all kinds of industrial processes. According to Stanford, the energetic material was believed to be refreshing and revitalizing and was therefore used in everything from spa treatments to consumables like radioactive water and chocolate. It wasn't all bad, however, as it also birthed the use of radiation in medical treatments for cancer, which continues to this day (via Mayo Clinic).

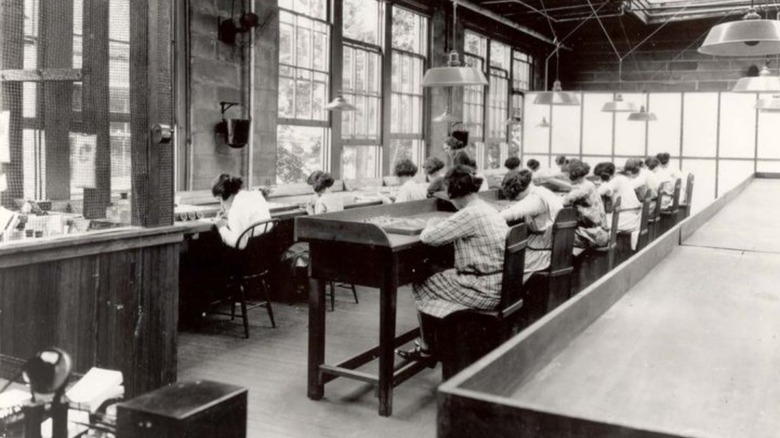

One of the most popular uses of radium was in luminescent paints. When combined with zinc sulfide, the paint would glow, making it perfect for reading your watch face in the dark. Factory workers for the Radium Dial Company would lick their paint brushes between applications in order to achieve a sharp point. That meant they were ingesting up to 2 grams of radioactive paint per day. Sadly, the dial workers who later became known as the Radium Girls suffered horrific radiation sickness and death.

Asbestos

Asbestos is a naturally occurring mineral material that was mined for industrial uses due to its strength and resistance to heat. The EPA notes that during the peak of its use, asbestos was included in building materials including roofing shingles, floor tiles, and insulation. Its resistance to heat also made it useful for things like automobile brakes, gaskets, fabrics, pipe coverings, and more.

As a result, for decades it was likely that a person could come into contact with asbestos almost anywhere. Beginning in the '70s, companies started to reduce or eliminate their use of asbestos after concerns about public health risk were realized (via Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry). However, while certain products no longer utilize asbestos, the material is still present in some construction or automotive materials and may be lingering in your environment if you have products that were manufactured before the '70s.

As the EPA notes, exposure to asbestos can result in lung disease including cancers and asbestosis, a progressive long-term disease of the lungs. The negative impact on the lungs makes one particular use of asbestos more terrifying than all the rest. During the 1950s, Kent cigarettes used crocidolite — a type of asbestos — as a filter material (via PubMed). Tests confirmed that fibers were released and present in the smoke of each cigarette. Those fibers were inhaled directly, putting users at significant risk. As of 2018, it's estimated that asbestos is responsible for 255,000 deaths annually.

Lead

Since at least the time of the Romans, lead has been used for everything from dishes to paint and fuel additives. It has a sweet taste — although eating it is not recommended — which contributed to its popularity in winemaking. It's also why a generation of kids munched on paint chips as an after-school snack: Out of 450 recipes found in the Roman Apician Cookbook, one-fifth of them are for the use of lead to enhance the flavor (via Dartmouth).

Lead's ubiquity was followed by countless calls to action throughout history. Vitruvius noted the negative effects of lead exposure all the way back in 14 BCE and Benjamin Franklin noted the same centuries later. Despite the concerns of prominent minds throughout history, humanity went full steam ahead with lead production and use.

Things came to a climax in the early twentieth century when General Motors began adding tetraethyl lead to gasoline as a way of boosting performance. It certainly did that, but it also exposed the world to deadly levels of lead. As a result, as many as 5,000 people died in the United States alone, every year for the next six decades. Eventually, people got wise, and lead was removed from fuel and other areas of life. Still, the legacy of lead poisoning lives on. According to the World Health Organization, nearly a million people still die of lead poisoning each year.

Mercury

Mercury, otherwise known as quicksilver or liquid silver, is the only elemental metal that is liquid at room temperature (via Britannica). For that reason, it is perhaps most well-known today as the liquid inside handheld thermometers. Because of its low melting point, it's useful for gauging temperatures in the range of the human body, but even those thermometers are falling out of favor. Many modern thermometers use other liquids or digital sensors (via Poison Control).

Long before thermometers were invented, mercury had its other uses. It was commonly used as part of a red pigment called cinnabar and may have been responsible for poisonings as far back as 5,000 years ago, according to Smithsonian Magazine. It may even have been intentionally consumed as a hallucinogen, but that remains unconfirmed.

Mercury really got busy contaminating people during the 18th century when it was commonly used in the production of hats to help transform the fur of small animals into felt (via History). The effects of mercury poisoning include tremors, speech problems, and hallucination and were common enough that the term "mad as a hatter" was coined.

Chemical pesticides

Humanity has had a long and complicated history with chemical pesticides. Perhaps the most famous of these is DDT, a chemical that was widely used in the middle of the 20th Century. Public support waned in the wake of Rachel Carson's book, "Silent Spring" (via Britannica).

DDT was first synthesized in 1874 but its insecticidal properties weren't realized until 1939. Thereafter, DDT was sprayed over vast areas to control the population of mosquitos, fleas, and other insects. It worked wonders until many insect populations developed a resistance to it (via Duke). Meanwhile, people began to realize that the chemical was accumulating in the soil and in the bodies of bugs, before making its way up the food chain to birds and other animals, including humans.

As a result, the use of DDT was restricted in the 1960s, although it's still used in some areas where the risk of insect-borne illness outweighs the risk of the chemicals themselves (via National Pesticide Information Center). While chemical pesticides have helped many communities by reducing the risk of illnesses transmitted by insects, the danger of human exposure to those same chemicals can't be overstated. According to a World Health Organization task force, it's estimated that as many as 20,000 deaths occur as a result of pesticide poisoning each year (via BMC Public Health).

Sarin gas

Speaking of pesticides, one accidentally led to the creation of sarin gas, a deadly nerve agent. Just before the start of World War II, in 1938, a German scientist named Gerhard Schrader was asked to create a new pesticide for killing weevils (via History). The bugs were threatening Germany's fields and orchards, so Schrader got to work. He mixed together phosphorous and cyanide, but the mixture was far too toxic for use in agricultural settings. The German military, however, was interested. Schrader then went back to the lab and worked on making the mixture deadlier still, and the result was sarin gas.

By the time the war was over, the Nazis had made roughly 12,000 tons of the stuff but never used it. The war might have played out quite differently if they had. Sarin gas is particularly dangerous because it's heavier than air, so easily sinks toward the ground and mixes in with water. People can be exposed by breathing it in or through contact with the skin or eyes (via CDC). Exposure can cause blurred vision, nausea or vomiting, convulsions, paralysis, and respiratory failure.

In 1994 and 1995, two terrorist attacks in the cities of Matsumoto and Tokyo, involving the release of sarin gas, resulted in the deaths of 19 people while 5,000 more were made ill but eventually recovered (via OPCW).

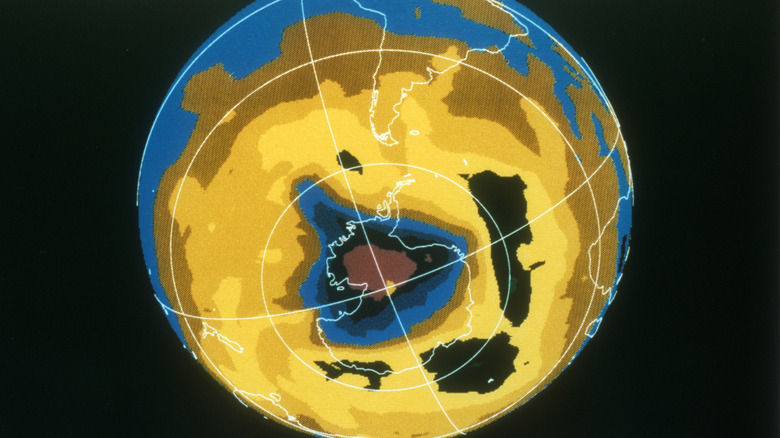

CFCs

Prior to the advent of CFCs, refrigerators used ammonia, methyl chloride, and sulfur dioxide as refrigerants, all of which are toxic and resulted in accidental deaths when they would leak out. Consequently, the search was on in the 1920s to find a safer refrigerant. That was achieved in 1928 when Thomas Midgley, Jr., an engineer for General Motors, synthesized the first CFCs (via NOAA).

Midgley is notable because he was also responsible for the introduction of leaded gasoline and is often touted as a candidate for the person who has caused the most harm to the world (via Interesting Engineering).

While CFCs served their purpose as a safer refrigerant, being both nontoxic and nonflammable, as well as providing an affordable means of air conditioning, they had some astounding — and unforeseen — consequences. In 1974, a scientific paper published in the journal Nature outlined the ways in which CFCs break down when they get into the upper atmosphere and cause damage to the ozone layer. Consequently, the Montreal Protocol was established in 1987, crafting guidelines around the use of ozone-degrading substances. In the intervening years, we've gone a long way to repairing the damage — but not before an unknown number of people died of skin cancer from increased sun exposure (via National Geographic).

TNT

Before TNT was the default label for every explosive ever used in a cartoon, it wasn't an explosive at all. German chemist Julius Wilbrand first synthesized TNT — known by its chemical name 2,4,6-Trinitrotuluene — in 1863. He was trying to make a yellow dye for clothing.

Its explosive potential wasn't realized until years later, owing to the relative difficulty of getting it to detonate. That same difficulty, however, is precisely what makes it useful. According to New World Encyclopedia, TNT can be melted using steam or hot water, allowing it to be molded into various shapes, including the interior of shell casing.

During World War I, the German military used TNT in armor-piercing shells, allowing for time-delayed explosives that went off after the rounds got inside British ships. The total number of people who have died as a result of TNT is unclear, but explosions weren't the only danger. Munitions workers inside TNT factories were known to suffer TNT poisoning, an affliction that turned the skin yellow and could result in death if the exposure was severe enough (via IWM).

Early surgeries

Today, we take medical operations for granted. It's not unusual to go into a hospital, have your body temporarily cut open, and go home later the same day none the worse for wear. Of course, that wasn't always the case, even relatively recently.

Prior to the invention of antiseptics and the general acceptance of germ theory, even successful surgeries often resulted in the death of the patient a few days or weeks down the line. Doctors understood that patients often succumbed to infections after going under the knife, but it wasn't widely understood why that happened or how it might be prevented.

One infamous operation from the 1800s involved Dr. Robert Liston and is reported to have had a 300% mortality rate, killing the patient and two bystanders (via PubMed). According to Gizmodo, the story goes that Dr. Liston was performing an amputation when he accidentally sawed through the fingers of the surgical assistant. Moments later, he cut through the coat of an elderly doctor who was observing nearby. The man wasn't cut but reportedly died of a fright-induced heart attack. Days later, both the surgical assistant and the patient died of infection.

James Lister's invention of antiseptics by way of carbolic acid turned the tide in the fight against germs, and not a moment too soon. Before that, you had a one in five chance of dying on the operating table and even if you survived, leaving the hospital alive was a coin toss (via BBC).

Global transit

Global transportation, the ability for people to get from one continent to the next relatively quickly, has had some objectively positive effects. For one, it has made us more connected and opened up the wonders of the works to more people than ever. It has, however, also made us more susceptible to disease and death.

As explained by PubMed, in the not-so-distant past, diseases could only spread as far as a person could travel on their own two feet, or else by horseback. That meant that even deadly diseases generally stayed within confined geographical areas. The advent of sailing ships allowed diseases to travel even further afield but the relatively slow transit times at least kept them somewhat in check. The invention of truly global travel through airplanes gave humanity a ticket to the world, but diseases are often stowing away on those journeys.

Airplanes and ships have helped to spread disease pandemics including cholera, HIV, influenza, SARS, and more recently, COVID-19. It's impossible to determine precisely how many people have died from exposure to diseases that they wouldn't have otherwise encountered without global transit. That is, unfortunately, a price we must collectively pay in exchange for access to the wider world.

High fructose corn syrup

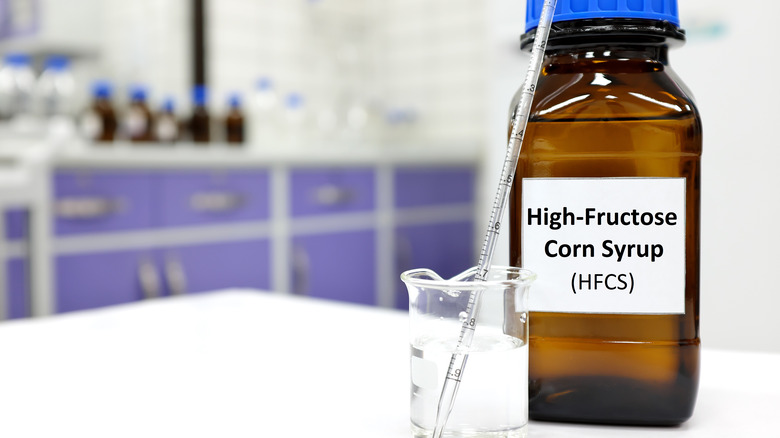

In 1957, Richard O. Marshall and Earl R. Kooi created glucose isomerase, which changes the composition of glucose in corn syrup and turns it into sucrose. The result was high fructose corn syrup (via Clark Street Press).

Thirteen years later, in 1970, high fructose corn syrup made its way into the food supply in the United States, in response to the rising costs of conventional sugars. Since then, it has made its way into just about every type of food you can imagine, from cereals and bread to sugary drinks. If it's sweet, it probably has high fructose corn syrup. It might have some even if it's not sweet (via Healthline).

While corn syrup has made its way into all manner of food products, if you're a soda drinker it's likely that's where you're getting most of it. There is some debate about whether or not high fructose corn syrup is actually worse for you than an equivalent amount of sugar, but there's evidence that it is. Mice who were given the equivalent of a soda a day saw increased tumor growth, (via Science) and high fructose corn syrup is likely contributing to increases in diabetes. According to Live Science, it's estimated that sugary drinks largely sweetened with high fructose corn syrup contribute to the deaths of 184,000 people every year. A cold soda does taste good, though.