What Is A Starquake? The ESA's Gaia Observatory Has Some Photos To Show You

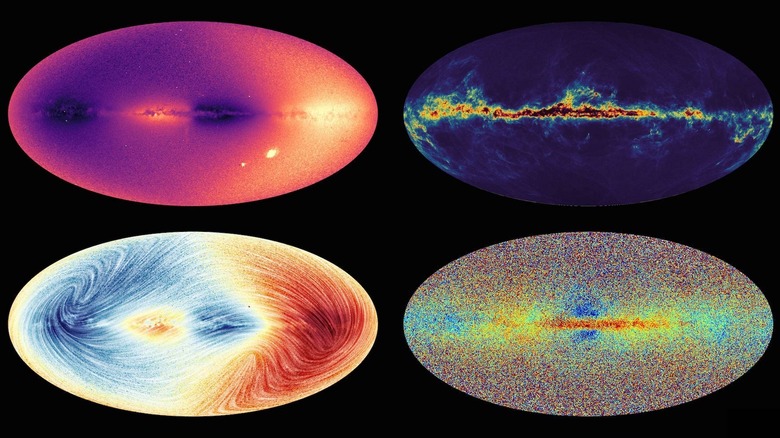

The European Space Agency (ESA) first launched the Gaia project back in 2013 with the intention of collecting more precise data about as many of the stars in and beyond our galaxy as possible. In fact, it managed to collect info on more than 2 million stars between the start of its collection in 2014 and the submission of its first batch of results in 2016 (22 months overall).

These instruments are so precise that the ESA claims it would be like someone being able to look at the moon — without any assistance — and finding a coin laying on its surface. With Gaia's help, researchers have been able to piece together clearer theories on things like how stars move, how the galaxy was formed, and how it could be evolving. And thanks to those instruments, Gaia has been able to detect things that it wasn't actually built for: starquakes that scientists previously didn't know existed.

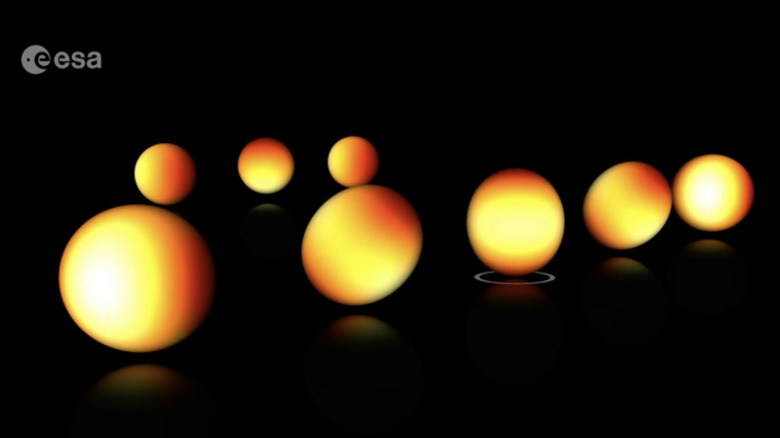

Vibrations that reshape stars

As for what starquakes actually are, well, they're basically akin to earthquakes — which makes sense when you think about both words, honestly. Starquake refers to motion on the surface of a magnetar star, of which only a couple dozen are known and they're usually quite small (about 15 miles across). The size of the star doesn't diminish the size of the starquake or its impact, though, as one such event in 2004 caused a very brief communications blackout and shifted the Earth's magnetic field (via Science Line).

Gaia was previously able to spot radial starquakes, which are vibrations that move outward in a somewhat circular pattern, but has recently detected other types of starquakes that the ESA didn't expect, too. These tsunami-like quakes, which have been shown to change the global shape of the stars they affect, are much more difficult for Gaia to pick up, but it has somehow managed to do just that. What's more, these almost imperceptible forms of starquake have been observed on thousands of stars, not just magnetars. That's something that calls the current theory of starquakes being limited to magnetars into serious question. According to Gaia collaboration member Conny Aerts of KU Leuven in Belgium, "Gaia is opening a goldmine for 'asteroseismology' of massive stars."