Hubble Space Telescope Just Uncovered A Fascinating Discovery

When a star approaches the end of its life and runs out of fuel, it detonates in an enormous explosion called a supernova. These events are dramatic and destructive; they can obliterate nearby stars and would render a planet like Earth uninhabitable if one happened nearby (via ESO). However, the Hubble Space Telescope has recently been studying a tough star that has survived its companion star going supernova, and the data collected could help astronomers learn about how stars evolve and die.

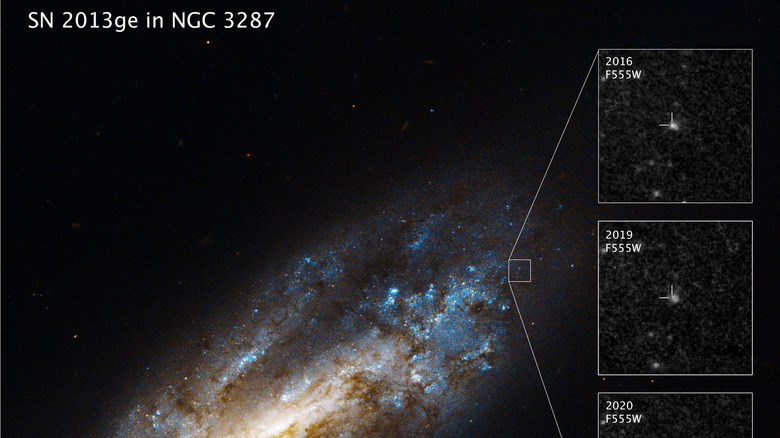

Researchers were looking out for a supernova because they wanted to know what happens to a star's outermost layer, which is composed of hydrogen, during an event like this. Sometimes, after a supernova, there is no evidence of hydrogen at all, which makes researchers wonder what happened to it. To answer that, the group used Hubble to look for examples of these "stripped" supernovae. They found what they were looking for in the 2013ge, which used to be a binary system before one star went supernova and left a companion star behind following the blast.

"This was the moment we had been waiting for, finally seeing the evidence for a binary system progenitor of a fully stripped supernova," said the lead author of the study, Ori Fox of the Space Telescope Science Institute (via Hubble). "The goal is to move this area of study from theory to working with data and seeing what these systems really look like."

A hydrogen mystery solved

When astronomers first observed supernova 2013ge, all they saw for several years was bright ultraviolet light from the explosion. But after time, the light began to dim and another source of ultraviolet light became visible: the companion star. By studying it, the researchers could test the theory that this star had siphoned the hydrogen off its companion before it went supernova. This was something that had been theorized to happen but had never been observed before.

"In recent years many different lines of evidence have told us that stripped supernovae are likely formed in binaries, but we had yet to actually see the companion," said another of the researchers, Maria Drout of the University of Toronto. "So much of studying cosmic explosions is like forensic science — searching for clues and seeing what theories match. Thanks to Hubble, we are able to see this directly."

Another unusual aspect of this supernova was that it showed two peaks in brightness, one after the other, rather than the usual one. The researchers think this is because the first peak was when the first star exploded, and the second peak is when the shockwave hit the companion star and jostled it. Despite being hit by this huge shockwave, the companion star survived.

However, the companion star will likely end up sharing its partner's fate and going supernova itself eventually. Then there will be a pair of black holes or neutron stars and depending on how close the two remnants of the stars are, they could either orbit each other or one could be flung out into the depths of space.