The Iconic History Of The Lamborghini Miura

In over a century of automaking, perhaps no car has had as dramatic an impact as the Lamborghini Miura. Built at a time when auto manufacturers were making giant strides in improving the performance and handling characteristics of the automobile, Lamborghini introduced a whole new way to think about what a road car can be.

Up to the time of its release, road-going cars were almost all driven by the back wheels, powered by an engine up front. The only exception to this had been the numerous rear-engine, rear-drive vehicles such as the VW Beetle and Renault Dauphine. By the mid-sixties, auto racing had found that handling is best with the engine placed as close to the middle of the chassis as possible to allow for even distribution of weight front-to-back. Nobody thought such a layout would work for a passenger vehicle — until the Miura.

Coming out with a mid-engined car for legal road use set the stage for high-performance cars and gave a roadmap for the future. The Miura defined a new class, the supercar, and became the blueprint for every top-speed chasing auto ever since. It has become the object of desire for generations of kids dreaming of fast cars and ownership goals for the wealthy auto enthusiast. The Miura has transformed from a desirable high-performance supercar to an investment in history. A true collectors' car, the Miura fetches auction totals in excess of a million dollars.

This is the iconic history of the Lamborghini Miura.

The company behind the car

Automobili Ferruccio Lamborghini S.p.A. began because of a wealthy Italian industrialist's displeasure with the experience he had owning exotic sports cars. Ferruccio began making tractors after WWII from leftover military equipment and built his company into a successful tractor manufacturer. Being that this brought him great wealth, he appreciated the finer things Italy had to offer, including Ferrari motorcars. Longtime Lamborghini test driver Valentino Balboni tells the story that Ferruccio loved his flashy and extravagant cars but was not a highly skilled driver.

As such, he had an issue of burning up clutches in his Ferraris. After taking them back to Ferrari for repair many times, he had his mechanic look at the cars and discovered one of his off-the-shelf clutches from the tractor factory was an exact replacement. Furious that he had been spending 1,000 lire on replacements that he had in inventory for just 10 lire, he brought it up to Enzo Ferrari himself.

Enzo did not take kindly to having a "farmer" telling him how to build his cars and berated him until Ferruccio stormed out of the office proclaiming that he would no longer buy Ferrari cars because he would build his own cars and do it better. And so in 1963 he set off to create what would become Ferrari's greatest competition — and it endures today.

The genesis of the car

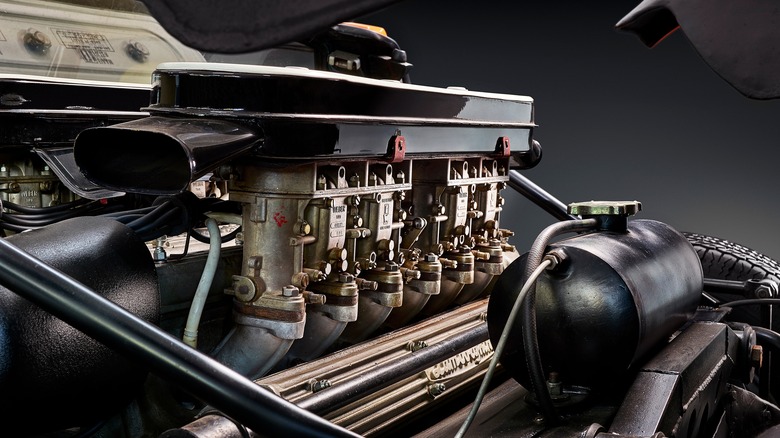

The first models produced by Lamborghini were front-engine Grand Touring cars that were much in line with the style of the fast cars of the day. They were fitted with an all-new V12 twin overhead cam engine produced by Lamborghini and designed by former Ferrari engine designer, Giotto Bizzarrini. The engine started out displacing 3.5L and was bumped up to 4.0L by 1966.

Ferruccio's young design team had concocted a plan to develop and produce a mid-engine car for the road, initially drafting the design on their own time before introducing it to the boss. At first, he was less than receptive to the idea as he wanted to concentrate on his GT cars, which were selling well for their young company. They managed to convince him to give it a green light by selling him on the idea of having a road-going car that could win on the track and bring in buyers.

Development of a design

The Miura development team consisted of Gian Paolo Dallara, Paolo Stanzani, and New Zealand race mechanic Bob Wallace. Styling of the car had been contracted out to Bertone, where now-legendary Marcello Gandini penned the beautiful lines that would become the Miura. The team of designers and engineers were a young bunch working in a young and small company, which meant they were unencumbered by the traditions and machinations of a legacy company and corporate culture more interested in cutting costs than turning heads. They had the authority to build something energetic and set out to do just that.

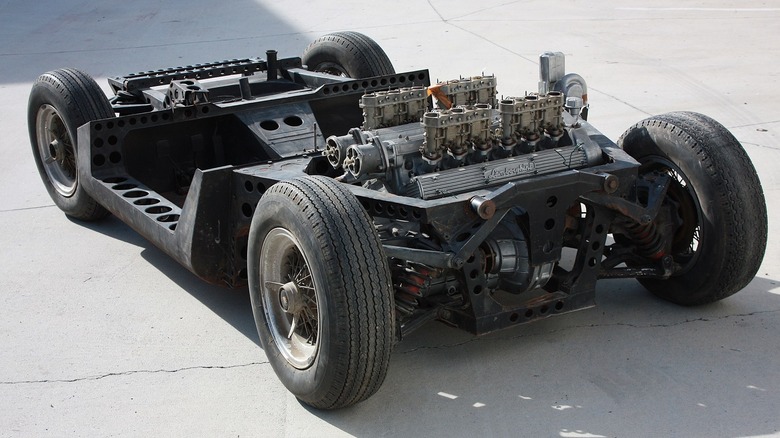

Starting around 1965, work began to take shape around the chassis, a steel tube frame with a central backbone from which all the components would hang. In order to fit the existing Lamborghini V12 engine, it was decided from the start that it should be installed longitudinally to save space. Inspiration for the engine came from the Austin Mini, as it too had a longitudinal engine. The engine and transmission connected together such that they shared the same oil, just like the mini. This engine setup saved the car from having an overhanging transaxle protruding far beyond the passenger compartment and way past the back wheels. As it was, all the weight was confined within the wheelbase (via The Lamborghini Miura Bible).

Building the prototype

After seven months Lamborghini had a rolling chassis to present at the 1965 Turin Auto Show. The car, though incomplete, caused a stir. In a bold move for a company founded only a few years before, Lamborghini presented a mid-engine chassis with a longitudinally-mounted engine unlike anything at the show. Ferruccio Lamborghini used this as an opportunity to have coach builders bid to develop and produce the body for the Miura. Nuccio Bertone made an impression and received the contract.

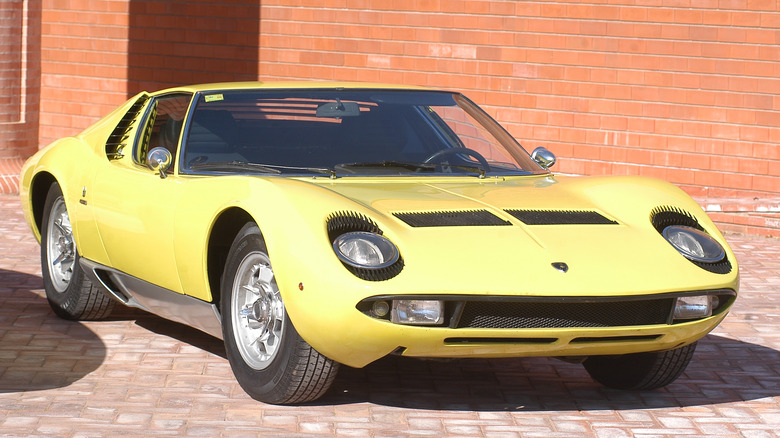

Bertone's styling for the Miura was headed by Marcello Gandini, who had only recently joined the firm to replace outgoing design chief, Giorgetto Giugiaro. Bertone had long been a designer of iconic Italian cars, but the Miura was Gandini's first chance to make his mark with a new model. By all accounts, he succeeded in creating one of the most iconic and beautiful machines on four wheels. Design updates given to Ferruccio were received with enthusiasm as the Miura's shape came into view.

Gandini had the car ready in time for the 1966 Geneva Motor Show. Shortly before it was ready, Gandini had left for vacation while Nuccio Bertone made a few subtle changes and had the car finished and painted, allowing him to have a hand in the final project with a sense of joy and pride.

Unveiling the Miura to the public

Once Bertone had completed the exterior, it was sent back to the Lamborghini factory, where Wallace and Dallara would fit the V12 and fine-tune the car to be show-ready.

It was at the 1966 Geneva Motor Show that the public first got to see the final production-ready bright orange Miura in the flesh. While 1966 had many fantastic new cars on offer for patrons, the presence of an all-new mid-engined passenger car caused at least one auto journalist to label the car "coruscating" although they did make note that, although the chassis had been seen the year before, they felt it was not yet completely sorted. Little did anyone know that Lamborghini had just entered a whole new class of car into the world, the supercar.

This was the beginning of the Miura's true legacy — now that the public and the automotive press had been given a chance to see what all the hype was about.

Manufacturing of the Miura

After the unveiling in Geneva, orders for the car came in immediately, and the factory in Sant'Agata started assembling cars and shipping them to customers. While Ferruccio declared the Miura to be his ideal sports car in 1984, he initially had only expected to sell about 50 of them, and he was very wrong. The car was popular and bought by big names of the day, including Miles Davis, who wrecked his car, breaking both his legs, and was then discovered by none other than film producer James Glickenhaus on the side of the highway.

The Shah of Iran, a notorious collector of fine automobiles, bought one brand new. His was a later model converted into a special edition called Jota and was eventually purchased at auction by actor Nicholas Cage. Just two years after production started, the Miura was made an icon of the movies, playing a starring role in the opening scene of "The Italian Job" starring Michael Caine. Far from Lamborghini's estimate of just 50 cars, the Miura ended up production having made 764.

Udgrades and special editions

Through its seven-year run, the Miura underwent a handful of changes, albeit minor. The 1968 Miura S received a bump of 20 horsepower along with a few upgrades to boost the car's comfort, such as power windows and optional air conditioning. 1971 saw the Miura SV with an upgraded engine producing 380 horsepower, up from the original 345 horsepower in the debut car, as well as further exterior changes such as the removal of the "eyelashes" around the headlights. These upgrades were well received, and the car cemented its legacy as an icon.

Lamborghini test driver Bob Wallace also created a special edition as a test mule for racing with several modifications meant to make it perform at optimal capacity around a race track. His car was called the Jota — as noted above — and it spawned 6 Miura SV/J special edition cars to be produced by the factory.

Legacy

Since the unleashing of the Miura onto the world stage, every high-performance car has been measured against the original. While dozens of mid-engine cars have been built, they all trace their lineage back to the Miura, as it was the first. Not only did it start a trend to mid-engine supercars, but in the styling department, Gandini nailed it from the start. The Miura is still widely regarded as the most beautiful sports car ever made, and it is hard to argue against that point. Today, when they come up for auction, prices regularly exceed one million dollars.

While the Sant'Agata factory today builds 800 cars in six months, it failed to meet that number in six years when the Miura was on sale. In the time since it was new, the Miura has taken on a legendary status that seems to rise each year, and with less than 800 cars built, their value may increase as more collectors come to value their importance in the history of the supercar.

While the Countach was the car of choice to adorn posters hanging on the walls of teenage kids in the eighties, rising interest in things of the past may yet put the Miura in that place more often than an Aventador or Huracan, both of which are built in such numbers they seem almost commonplace in some cities.