Is California Banning Diesel Trucks? Here's What You Need To Know

When California issued its Advanced Clean Fleets rule in 2022, proponents hailed it as a forward-reaching effort in the most populated state's battle against air pollution. In it, regulators banned the sale of new diesel-powered medium- and heavy-duty trucks by 2036, making it the world's first ban of diesel-powered fleets. In the plan to transition the market to more sustainable alternatives, manufacturers and operators were required to phase out all non-zero-emission big rigs, garbage trucks, and heavy-duty delivery vehicles by 2042. The move, unanimously approved by California's Air Resources Board, was to be a major step toward cleaning up a goods-transportation industry that heavily contributed to the state's air pollution due to its dependence on emission-heavy diesel engines.

This potentially revolutionary regulation is now on the shelf, as California dropped its groundbreaking legislation ahead of President Donald Trump's inauguration in January 2025. The outgoing Biden administration, although approving the state's ban on new gas-powered car sales, had failed to approve California's newest limits on diesel emissions for the trucking, commercial harbor, locomotive, and refrigerated-transport industries. Now companies in those industries wait to hear the future of California's efforts to reduce diesel emissions.

Why California banned diesel

When California first enacted its diesel truck ban, it aimed to reduce the greenhouse-gas emissions of an industry disproportionately responsible for the state's air pollution, accounting for a whopping 31% of California's nitrogen oxide pollution and over 50% of particulate matter pollution despite only accounting for 6% of vehicles on its roads, according to the Natural Resources Defense Council.

California's status as the country's largest shipping hub, transporting almost 30% of the country's exports, made banning diesel trucks critical to reducing emissions from the state's freight industry. For example, trucks transporting goods from three of the country's eight largest ports, including its top two in Los Angeles and Long Beach, were significant contributors to the state's pollution issues. According to the New York Times, 40% of California's greenhouse emissions come from transportation.

This pollution takes a toll on not only the state's climate but also its residents' health. Researchers at the University of California, Irvine, found the pollution caused by heavy-duty-transportation trucks caused roughly 483 premature deaths and 15,468 asthma attacks in 2012 alone. Furthermore, the Air Resources Board said diesel exhaust is responsible for 70% of the state's cancer from airborne toxins, a health crisis disproportionately affecting the low-income and minority communities traditionally located near transportation hubs. In a state that houses six of the country's seven most polluted metropolitan areas, reducing diesel emissions was more than a measure to reduce climate change — it was a social-justice measure targeting a burgeoning health crisis.

Why California recalled its diesel regulations

To understand why California dropped its ban, you first need to know how the state could enact it in the first place. In 1970, Congress passed the Clean Air Act, preventing states from unilaterally instituting vehicle emission standards. However, it also let California pass stricter pollution rules to combat the state's unique smog issues, enabling moves like California's ban on gas-powered-vehicle sales. The federal government retains oversight, requiring the state to request a waiver from the Enivronmental Protection Agency for each new standard. Over the course of 50 years, the EPA has only refused once — a decision rescinded less than a year later.

This hands-off approach changed during the first Trump administration. Staunchly against the state's tighter restrictions, a major tenet of the administration's environmental agenda was to revoke California's special status. But the Biden administration withdrew the Trump-era revocation in 2022, reinstating the Golden State's ability to set its own emission standards.

A year later, the California Air Resources Board passed the Advanced Clean Fleets rule. When California dropped the rule in 2025, it did so knowing the new Trump administration would strike down its waiver request. As board chair Liane Randolph said in a widely reported statement, "Withdrawal is an important step given the uncertainty presented by the incoming administration that previously attacked California's programs to protect public health and the climate." Whether the move is part of a broader strategy to keep the state out of the administration's sights is unconfirmed.

California's lost diesel standards

The Biden administration's inability to approve California's new restrictions before the election was a major blow for a state looking to 'Trump-proof' its environmental policies. The lost mandate, which applied to companies with 50-plus trucks or $50 million in annual revenue, required firms to convert their fleets to zero-emission electric models by 2042. Truckmakers, for their part, needed to phase out diesel-powered heavy- and medium-duty truck sales by 2036.

Beneath these broad restrictions, each vehicle type was subject to different enforcement timelines. The swiftest were the trucks transporting cargo from California's bustling ports. All new sales of these heavy-duty vehicles would have needed to meet zero-emission standards by 2024, while the companies that operated them needed to convert their entire fleet to electric by 2035. Exemptions were given to emergency services, including ambulances and fire trucks.

Along with the diesel-truck ban, California had implemented new rules reducing the emissions of several transportation industries. One was a controversial ban on non-zero-emission locomotives operating in the state by 2035, with any diesel trains built before the turn of the century banned from California's tracks in 2030. The railroad industry balked at the new standard, claiming that the swiftness of the change was not technologically viable. Commercial harbor craft, including tugboats and ferries, had been subject to similar emission requirements. California also pulled its regulations phasing out the transport refrigeration units powered by diesel combustion engines typically seen on shipping containers, railcars, and heavy- and medium-duty trucks.

An uncertain regulatory future

While California will probably wait until 2029 before reintroducing its new emission standards, the battle over its current emission regulations rages. Shortly after the inauguration, the Trump administration targeted the Golden State's electric-vehicle mandates by asking Congress to review the Clean Air Act provision enabling them. Their supporters pushed back, with the Senate parliamentarian denying the proposal. The administration also requested that Congress review other California energy rules, including particulate-matter and nitrogen-dioxide limits and a directive to transition half of the state's heavy-duty-vehicle sales to electric by 2035.

California's status as the nation's largest economic market has not only made it a regulatory trendsetter but a key inflection point for an administration looking to bolster fossil-fuel production. Already, 11 states have adopted California's gas-powered-car ban, and some, like Illinois, continue to mull adopting the now-defunct diesel truck ban. Combating this influence has, once again, become a major part of the administration's environmental platform.

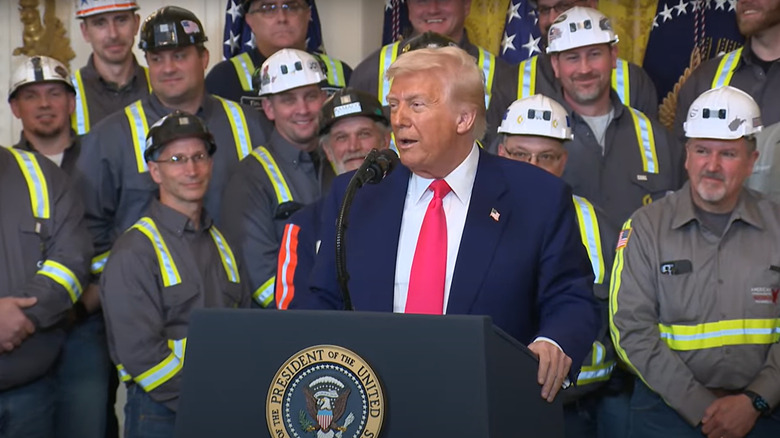

On April 8, President Trump signed an executive order bolstering the nation's "beautiful clean coal" industry by removing regulatory restrictions on the resource's production. In the accompanying fact sheet, the administration said it's "committed to halting efforts by individual states to impose their regulatory preferences on the entire nation," adding that California's vehicle-emissions standards "would have forced automakers across the country to comply with the state's extreme environmental rules." California Gov. Gavin Newsom responded, "California's efforts to cut harmful pollution won't be derailed by a glorified press release masquerading as an executive order."

The fight continues

As April's tit-for-tat suggests, the fight over California's anti-pollution legislation will continue throughout Trump's administration. The administration will seek to dampen California's clean-energy push by targeting the state's cap-and-trade program – a first-of-its-kind effort in the U.S. that limits companies' greenhouse-gas emissions and incentivizes them to profit from going green by selling unused credits.

Another tactic will involve pulling federal funding meant to encourage the shift toward electric fleets. Already, the administration has sought to revoke $20 billion in Biden-era clean-energy initiatives, which included $1.1 billion in grants helping transition California's ports to zero-emission fleets. Further action will likely target several California energy and infrastructure projects, including billions of dollars earmarked for truck charging.

This is not to say that the state's emission restrictions have been for naught. California still has options, including state and local funding, state tax incentives, and the cap-and-trade program that, for now, remains intact. Undermining confidence is the state's lack of consistent success in converting its ports' fleets. In 2024, a Los Angeles Times investigation found that 92% of newly registered trucks at the Los Angeles and Long Beach ports were still powered by diesel engines. Much like consumers' problems with EV prices, high costs and a still-developing charging infrastructure have made the transition to EV trucks difficult.

So while Californians have chosen EVs in record numbers, the same can't be said (yet) for California's trucking industry. Still, California regulators remain confident. Just a few weeks after pulling its diesel-ban request, California opened America's largest port charging depot, signaling that the push to electrify its ports is far from over.