When Were Power Lines Invented & How Was Electricity Transmitted Beforehand?

Electricity is the movement of electrons between atoms. Its "discovery" is credited to a host of people, not the least of whom is an American legend, genius, and one of its founding fathers, Benjamin Franklin. In 1752, Franklin sent a kite with a metal key attached to the string up into a thunderstorm. As hoped, a lightning bolt struck the kite and sent electrical sparks down the string, proving static electricity and lightning were one and the same. However, it was by no means when this phenomenon was first "discovered."

Little did Franklin know that there would eventually be a spiderweb of electrical lines crisscrossing the globe that not only harnessed electricity but brought it directly into homes and businesses. Power lines came into existence in 1882 in Germany, but the concept was known to the ancient Egyptians as far back as 2750 BCE, who realized the Nile catfish could generate a jolt. This shouldn't come as a shock since they were also making beer on a massive scale 5,000 years ago. In 600 BCE, the Greek philosopher, scientist, and mathematician Thales of Miletus rubbed a piece of amber with a piece of silk (or fur) and created an attraction known as static electricity.

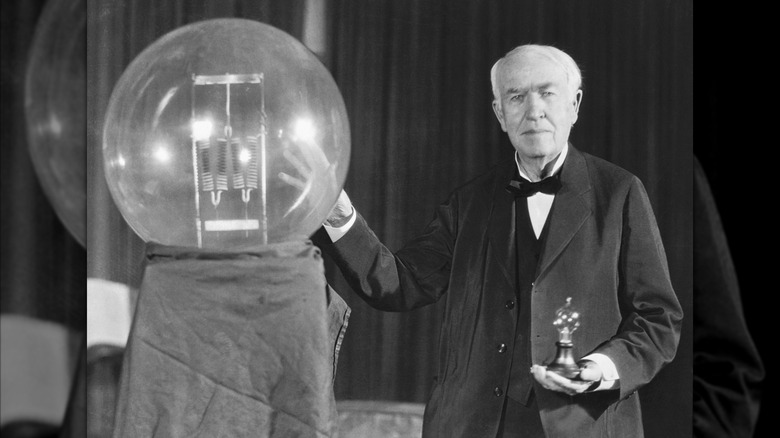

Thomas Edison helped light the way

In February 1879, Mosley Street in Newcastle upon Tyne, England, was the first street lit by incandescent light bulbs, which Englishman Joseph Swan had invented the year before. In April, twelve new and improved arc lamps attached to a small generator created by Charles Brush were used to illuminate Monumental Park in Cleveland, Ohio, becoming the first outdoor public space in the U.S. to be lit by electricity. Meanwhile, California Electric Light Company, Inc. (now PG&E) sold electricity to the public for the first time using two of Brush's generators to power a mere 21 arc lamps.

Enter Thomas Edison, who was instrumental in electricity's leap despite not being the first to invent the light bulb. On New Year's Eve of 1879, he unveiled a bulb (one of six scientific achievements thought impossible) that lasted about 40 hours — much longer than Swan's — and was thus far more practical. By 1880, he'd exponentially increased the life of his bulb to 1,200 hours.

In 1878, he founded the Edison Electric Light Co. in New York City. When he turned on his Pearl Street power station in 1882, it became one of the first centralized electric plants in the world. Six dynamos sent power through 80,000 feet of underground wires to a square mile of lower Manhattan that included Wall Street. Only 82 customers with 400 lamps were initially lit (although 1,284 were connected), but over 10,000 were getting power by the following year.

Electricity was an expensive luxury

Early customers all had to be within half a mile of the power plant because each light was hardwired directly to the generator using bare copper wires with very little cotton insulation. Voltage regulators were yet to be introduced, so the brightness of these new-fangled lights would routinely fluctuate, especially as more of them were turned on at night. As one might expect from "hot" wires that weren't grounded, the potential hazard was extreme and often resulted in fire or severe electrical shock.

Centralized stations weren't the only means of providing power in those nascent days of electrical distribution. Edison also created "isolated" power stations that sent power to just one customer. This luxury was only affordable to the wealthy, as it was easier to convince one rich person to pay for the convenience than a throng of hard-working folks who needed a much bigger central station. By 1886, 702 isolated and 58 central stations powered over 300,000 lamps.

In 1882, Oskar von Miller and Marcel Deprez, early pioneers of direct current (DC) in Germany, transmitted 1.25 Amps of current using an iron telegraph wire 35 miles between Miesbach and Munich. It only lasted a few short days but was considered the first successful long-distance transmission of electricity over a "power line."

AC versus DC was the war of currents

The problem with direct current is that there was no simple (or inexpensive) way to raise or lower the voltage if needed. Power was also lost based on the length of the wire, so DC was only viable up to a mile away from the main plant. In 1883, Nikola Tesla built a transformer, the Tesla Coil, that converted low-voltage electricity into high voltage, facilitating its use over much longer distances. The following year, he created a paradigm-shifting alternator that produced alternating current (AC).

1884 also saw Los Angeles become the first U.S. city to replace its gas street lights with electric ones, totaling 242 lamps with a circuit length of 85 miles. In England, Sir Charles Algernon Parsons built the first steam turbine generator, which, as it turned out, was much better suited than the old massive coal-fired reciprocating steam engines whose size, noise, smoke, and constant shaking had become big public nuisances.

In 1886, William Stanley, Jr. (United States) created the induction coil transformer and an early electric system that utilized AC instead of DC. Two years later, Tesla unveiled the first polyphase AC electrical system, which included everything needed to generate electricity (generator, transformers, transmission system, motor, and lights). George Westinghouse of the Westinghouse Electric Company, who would go on to become a juggernaut in the field (including kitchen appliances), immediately bought the patents for Tesla's system.

Hydropower got the power lines going

In 1889, a company founded by Charles Brush constructed the first long-distance 4,000-volt direct current transmission line in the U.S. The 13-mile power line ran from the power station at Willamette Falls in Oregon City, Oregon, to an arc lighting system in downtown Portland, Oregon. The first 4,000-volt alternating current line was built at the same spot a year later.

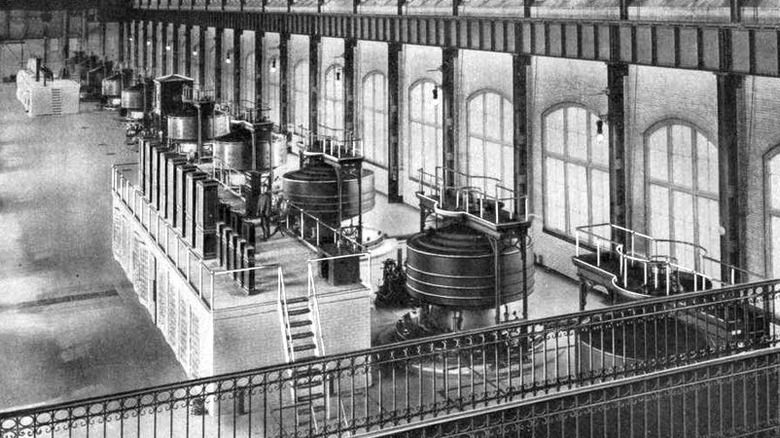

The first true high voltage line was built in Germany in 1891, sending a shocking 25,000 volts from a hydroelectric plant in Lauffen, some 108 miles to Frankfort. Using hydropower to produce electricity was a revelation that U.S. power companies tapped into. In 1893, a 22-mile AC line sent electricity from Folsom Powerhouse to Sacramento, California.

The first hydropower station at Niagara Falls — built by Tesla and Westinghouse — opened in 1895. A year later, a new AC powerline sent electricity to customers 20 miles away in Buffalo, New York, and by 1900, 15 long-distance transmission lines were operating around the country. Each was connected to a hydroelectric power plant that sent out as much as 40,000 volts to the masses. In 1901, the first power line between the U.S. and Canada was established at Niagara Falls.

And the rest is history. With all of its zig-zagging power lines, the North American Power Grid is not only the largest machine in the world but is considered one of humanity's greatest engineering achievements.