10 Of The Strangest Military Helicopters Ever Made

Vehicles are an important element in any army since they can fill a variety of battlefield roles. However, the last time a nation's military assumed a new war would be fought like the previous one, they invented an impractical 80 ton behemoth of a tank. As war is constantly changing, engineers have to consistently adapt and reinvent combat vehicles to suit the military's needs. And sometimes redesigning military vehicles goes a bit beyond the pale, defying both common sense and standard aesthetics.

While the advent of helicopters changed how many armies function, defense forces tend to use some of the strangest helicopter designs on the planet. The CH-47 Chinook, for instance, cuts a unique silhouette due to its elongated shape — a consequence of being designed to serve as a transport and a search and rescue vehicle. No other helicopter looks like the Chinook except for its predecessor, the Piasecki H-21, which is curved just enough to resemble a flying banana.

However, for as undeniably weird as the Chinook and H-21 are, these aerial oddities are actually normal compared to the weirdest helicopters ever built by or for a military. Just how weird can they get? How about a helicopter that can fold away like a step ladder or a helicopter with rotors so close together they look like they should shred each other apart.

Keep reading to find out just how strange and eccentric helicopter concepts can get when the designer is working for the military.

CH-37 Mojave

A helicopter's movement is completely governed by its central spinning blades. But depending on the design, sometimes the engine or engines that power them need to be placed outside of the main helicopter body.

The Sikorsky CH-37 Mojave was not only one of the worst military helicopters ever made, it was also one of the weirdest. A heavy-lift cargo/transport helicopter, the Mojave was designed to ferry equipment from place to place, and the weirdness started with how it loaded cargo. Whereas the Chinook utilizes a simple ramp in the rear — which makes the helicopter look like a cartoon frog — the Mojave utilized a much weirder set of swinging hatches in the front. These loading doors made the helicopter look like an ant opening its mandibles to swallow or regurgitate cargo. However, that weird design choice was only one side effect of its purpose.

Since the Mojave was intended to carry as much heavy freight as possible, engineers were left with little room for the engines. So instead of sacrificing cargo capacity, they just put the engines on the outside of the fuselage. The helicopters' immediately recognizable nacelles housed the vehicle's engines, which gave it an almost hammerhead shark-like appearance. And many helicopter pilots and crews thought so, too, as they often painted eyes on these engine bulbs. While the Mojave wasn't the only helicopter to bear these engine nacelles (the experimental Kellett XR-10 did as well), they looked more out of place on this vehicle than most.

Kaman HH-43 Huskie

While most helicopters have one central body rotor, some utilize two. The aforementioned CH-47 Chinook is one such design, as it needs the extra lift due to its elongated body. However, the rotors are located so far apart that nobody is ever afraid they will touch. The same can't be said for other twin-rotor helicopters.

The Kaman HH-43 Huskie and its variants were boxy helicopters designed for search and rescue and firefighting operations. While square bodies are unusual enough, the Huskie's claim to oddity fame lay in its "intermeshing rotor" layout. Unlike the Chinook, these rotors were placed directly next to each other, which sounds like pilots flirted with danger every time they started up the vehicle. However, the blades spun in opposite directions and were offset enough to ensure they wouldn't tear each other apart. Moreover, this novel design precluded the need for tail rotors, which are usually included as a counterbalance to the main rotor.

In the spirit of fairness, the Huskie's intermeshing rotor design wasn't unique, but it is a signature element in Kaman machines. The company used this design for other helicopters, including the Kaman K-MAX. Other manufacturers used intermeshed rotor concepts for vehicles such as the Flettner FI 282 and the SNCAC NC 2001 Abeille, but Kaman's stabs at the design were possibly the most successful. However, since few if any modern helicopters utilize intermeshed rotors, that's not saying much.

Hiller YH-32 Hornet

Usually, an engine (or two) is enough to create the required torque for helicopters' rotor blades to generate lift and propulsion, but some designers experimented with giving this one's blades an extra push, figuratively and literally. The Hiller XHOE-1 Hornet, alternatively known as the Hiller YH-32 Hornet (not to be confused with the Hiller HJ-1 Hornet), was an experimental ultralight helicopter designed to maximize lifting power while reducing the weight of the vehicle's frame.

However, the vehicle's most notable feature was the Hiller 8RJ2B Ramjets attached to the end of each blade. These jets hypothetically provided an additional 90 horsepower, but the design had more drawbacks than boons. The biggest issue was with the ramjets themselves. Should something go wrong and the engine stops working mid-flight, most helicopter blades "autorotate" and slow freefall descent to just under 30 feet per second (9 meters per second), but due to the design of the ramjets and the toll they took on the rotator blade angles, the Hornet fell at a much deadlier 49 feet per second (15 meters per second).

Other helicopters attempted similar designs. The aforementioned HJ-1 Hornet also utilized ramjets, but it ran into the same issues as the YH-32. The Hunting Percival P.74 and Sud-Ouest SO.1100 Ariel experimented with jets attached to their blades, too. One of the few successful attempts at a ramjet-driven helicopter was the Sud-Ouest SO-1221 Djinn, though it wasn't exclusively a military project — some filled agricultural roles, mostly crop dusting.

Hughes XH-17

While some helicopters are designed for shipping cargo, they don't have enough horsepower to carry much. Like most transport vehicles, a helicopter's maximum load is determined by its size. Bigger helicopters mean more and heavier cargo, but to stay aloft, its blades need to be enlarged — sometimes to a ludicrous degree.

The Hughes XH-17 was an experimental helicopter intended to test a tip-jet-powered rotor system. It wasn't custom-built from the ground up. Instead, the "vehicle" was frankensteined together using parts from different superplanes, including a North American B-25 Mitchell and a Boeing B-29 Superfortress. To be frank, the only component remotely helicopter-ish about the XH-17 was the blades.

To describe the XH-17's rotors as anything other than "monumental" would be a gross understatement. With a diameter of approximately 130 feet, the XH-17 produced enough lift to hypothetically carry up to 50,000 pounds, thus earning it the nickname "Flying Crane." However, a side effect of this carrying capacity and lift was a truly ear-shattering sound. According to reports, people could hear the XH-17's rotors up to eight miles away, which caused no shortage of noise complaints during testing. While the XH-17 never made it to production, it lived on in spirit thanks to the much smaller and economic Sikorsky CH-54 Tarhe. What that helicopter lacked in size and thunderous rotor blades it made up for with a comical empty space where most of the vehicle should have been. Although, that just left more room for cargo containers.

Mil V-12

Rather than building a helicopter so big that it requires blades that sound like thunderstorms, this alternative solution was to build a vehicle that blurred the line between helicopter and airplane.

At first glance, you would have been forgiven for assuming the Soviet Mil V-12, aka The Homer, was a cargo jet. After all, it was shaped like one — wings, wheels, tail fin and all. However, each wing was tipped with a large vertical rotor blade. This unique design let the vehicle lift off without a runway and gave it the classification of "helicopter." Moreover, the V-12's extended fuselage made it ideal for transporting weapons such as intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs). After all, it was designed during the Cold War.

Despite looking like a finished product, the V-12 was a prototype, and a failed one at that. The first test flight ended badly when the vehicle touched down harder than intended, which damaged the helicopter. This accident was attributed to harmonic vibrations, a consequence of the V-12's prodigious size and the control mechanisms required to pilot it. While the second prototype proved more stable, the vehicle languished in development for so long that it outlived its intended purpose (ferrying ICBMs). Soviet leaders decided to scrap the project. Currently, the first prototype is housed in the Mil Moscow Helicopter Plant, while the second is on display at the Central Air Force Museum in Monino, Russia.

Focke-Wulf FW 61

While many modern airplanes resemble one another, the early days of plane development was the Wild West of vehicle design. Everyone and their grandmother had a wacky idea of what a plane should look like, but only a handful approached functionality. Early helicopters channeled this same energy, so much so that one of the first practical ideas doesn't look much like anything we'd now recognize.

The Focke-Wulf Fw 61 is widely regarded as the world's first fully functioning and practical helicopter. Designed by Professor Heinrich Karl Focke in the late 1930s, this vehicle had the body and front-facing propeller of a plane from that era. However, instead of wings, the vehicle utilized two large scaffolds with vertically-oriented rotor blades on the ends. While the Focke-Wulf Fw 61 wasn't the first helicopter to fly in Europe — that honor goes to the lesser-known Breguet-Dorand — it stayed aloft for 28 seconds during its first test flight in June of 1936, thus demonstrating its superior design.

Admittedly, the Focke-Wulf Fw 61 was built to serve as a proof of concept, which raises the question of why we consider it a military vehicle. As you might have guessed, this proto-helicopter premiered during the early years of the Nazi regime. The Focke-Wulf Fw 61 proved so successful, Focke designed several helicopters that Nazi forces used during World War 2, such as the Focke-Achgelis Fa 223 Drache. This search and rescue helicopter utilized the same plane body and twin-rotor layout as the Focke-Wulf Fw 61.

De Bothezat Flying Octopus

As previously stated, the Focke-Wulf Fw 61 was the first fully functional and practical helicopter design, but not the first helicopter design. An earlier idea involved far more rotors than we are accustomed to.

In 1921, the U.S. Air Service contracted Russian scientist George de Bothezat to create a vehicle utilizing his "theory of lifting screws" — what we now call helicopter rotors. The result was simply known as the de Bothezat Helicopter, but its design was so unusual that it earned the nickname "the Flying Octopus."

Since de Bothezat constructed his conceptual helicopter before any standardized design ideas (and without testing models or wind tunnels), his titular helicopter looked quite comical. Instead of utilizing one central rotor and one smaller tail rotor, the test vehicle boasted four six-bladed rotors that fanned out from a central point via steel framework, as well as two horizontal steering propellers. This layout created a radially symmetrical body plan, not unlike an octopus. Pilots dubbed the helicopter "the Flying Octopus" because, according to author and helicopter pilot James R. Chiles, "the ideal pilot would have as many appendages as an octopus." Despite the de Bothezat Helicopter's ungainly appearance, during the first test flight, the vehicle managed to hover almost two meters off the ground for 1 minute and 42 seconds. And during the second test in January of 1923, the Flying Octopus carried four passengers. While the Flying Octopus was stable during testing, the U.S. Army lost interest.

Piasecki X-49 Speedhawk

Helicopter rotors are a double-edged sword. The design serves as both lift and propulsion, which gives helicopters far more mobility than planes. However, as a tradeoff, even the fastest military helicopters chug behind airplanes by a wide margin. Some helicopter concepts tried to change that.

The Piasecki X-49 Speedhawk was an experimental helicopter based on the Sikorsky SH-60 Seahawk, which in turn was based on the iconic UH-60 Black Hawk. The biggest change to the Seahawk design was its proprietary "Vectored Thrust-Ducted Propeller" (VTDP). This unit, which added small wings to the main body and replaced the standard tail rotor with rear-facing blades, was intended to significantly boost the helicopter's horizontal velocity. The VTDP also made the Speedhawk look like a toy helicopter you would find in a G.I. Joe action figure playset.

While the Seahawk isn't the absolute fastest helicopter out there, it can still travel at a respectable 170 mph. During testing, the Speedhawk shot past that record at a whopping 207 mph. This performance let the Speedhawk sneak into the third place spot of the "fastest military helicopter" list, right between the CH-47F Chinook (195.7 mph) and the Mi-24 Hind (228.9 mph). At least, that's what we'd be saying if the Speedhawk had ever exited the experimental phase and entered full production.

Curtiss-Wright VZ-7

We've seen flying cars in sci-fi stories for almost as long as there have been sci-fi stories, and many people want to own one in real life. Manufacturers are still working on the concept today, but if they are anything like earlier attempts, successful ones might be classified as helicopters.

During the 1950s and 60s, the U.S. Army experimented with the idea of a "flying jeep." One such concept was the Curtiss Wright VZ-7. The test machine was developed by the Santa Barbara Division of Curtiss-Wright and consisted of four rotors on the sides of a simple, rectangular open-air platform. The VZ-7 truly did look like a flying jeep. But while the machine excelled in stability and ease of operation, it lacked altitude and speed performance. Ultimately, the U.S. Army turned down the design.

Two other flying jeep concepts included the Piasecki 59/VZ-8P Airgeep (that's how they spelled it) and the Chrysler VZ-6. Unlike the Curtiss Wright VZ-7, these test vehicles had large rotors at the front and back and were classified as vertical take-off and landing (VTOL) aircraft instead of helicopters. Unfortunately, neither concept was greenlit, and the Army ultimately grounded the idea of utilizing flying jeeps. It didn't help matters that the VZ-6 accidentally flipped itself over and damaged itself beyond repair during its initial test flight.

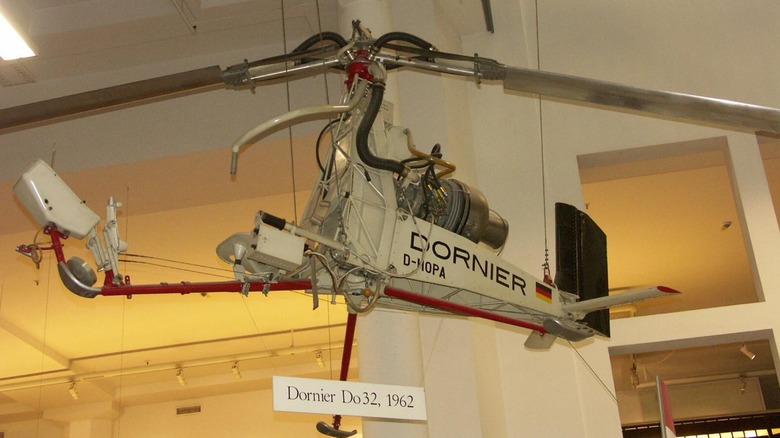

Dornier Do 32

Despite appearances to the contrary, helicopters are not light. Even the smallest ones weigh several tons — a far cry from the largest and heaviest military helicopters, but still more than most consumer cars. Some engineers came up with a way to lighten the load, which also had the added benefit of making helicopters more portable.

After World War 2, Germany was economically devastated, so the country's various industrial sectors had to come up with different ideas to stay afloat. One of the first products brainstormed by Germany's newly de-Nazified aerospace industry, specifically its helicopter division, was the Dornier Do 32. This ultralight, one-seat helicopter was less than 12.5 feet long and around three feet wide. And, the Do 32 could collapse into an even smaller container. Users could tow the helicopter by hitching the container to their car, and assembly took only five minutes. Plus, thanks to the helicopter's diminutive size, the transport container could double as a takeoff and landing pad.

Since Germany wasn't allowed to have a standing army, the Dornier Do 32 would have fulfilled more intelligence-gathering roles. The helicopter's manufacturer, Dornier Flugzeugwerke, had high hopes for the vehicle and even showed it off at the 1963 Paris Air Show. The company even began work on a two-seater model intended for German governmental agencies. However, interest in the helicopter evaporated. Currently, only one Dornier Do 32 prototype exists and can be found in the Deutsches Museum in Munich, Germany.