What Are Winglets For? Why Airplane Wings Are Curved Up At The End

In one of the most famous "Twilight Zone" stories, an airline passenger looks out the window of a commercial plane and is horrified to see a monstrous gremlin on the wing. If you were to do the same and look out the window of a modern jet, you won't see any monsters (hopefully), but there's a good chance you'll see the wing curving upward into a narrow tip. Don't worry — that's perfectly normal. That tip is called a winglet, and commercial airlines have been incorporating them into the design of their smaller and medium-sized planes for the past few decades.

Winglets are used by airlines for a good reason — they save companies money by allowing airplanes to fly more efficiently, which reduces fuel expenses. Most airlines are notorious for trying to make as much profit as possible, adding fees for baggage, Wi-Fi, and even snacks in some cases. Considering how expensive jet fuel can be, using winglets allows airlines to save money without adding costs to their ticket prices.

Testing new prototypes and building new aircraft is also very expensive, which is why airplanes don't change designs very often. The fact that winglets have become so widely adopted is a testament to how well they work. It also helps that they don't need costly components or sophisticated electronics to perform their function. Winglets are curved up at the end, and it's not because it looks cool — this shape is the very reason why they make planes more fuel efficient.

Flying without winglets is a drag — literally

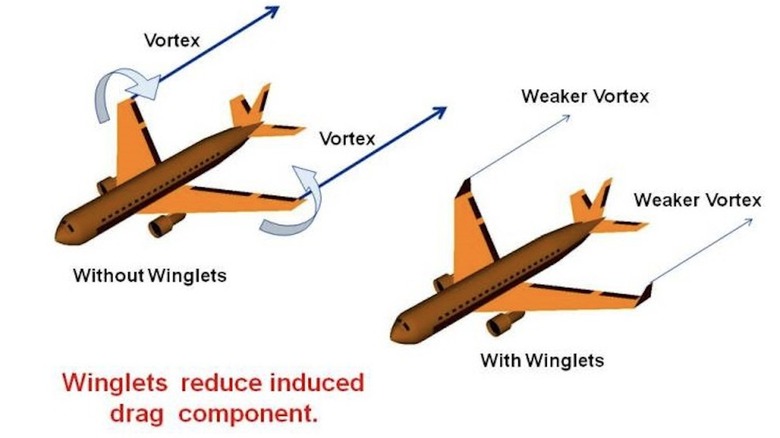

The curved design of winglets make planes more efficient because of the way aerodynamics work. Long story short, airplanes can fly because air pressure is higher under a plane than it is over, allowing the plane to generate enough lift to overcome Earth's gravity. Because of this principle, airplanes can even glide without power for dozens of miles. However, the design of a typical airplane also creates induced drag, because the higher pressure air meets the lower pressure at the wingtips, creating a vortex behind the aircraft as it flies forward. In order to combat this drag, airplanes must increase thrust — which means burning more fuel.

With a curved tip, some of the airflow around a wing is redirected back toward the plane, which reduces the strength of these drag-causing vortices. You can see the physics of how this works by going outside and watching a bird fly. Scientists have been studying how the wings of a bird create lift for literally thousands of years. Many species will curl the feathers at the ends of their wings upward when they need additional lift.

Even before the Wright Brothers first took off from Kitty Hawk, British scientist Frederick W. Lancaster patented "wing endplates" — rudimentary attachments that help reduce drag at the wingtips, though not nearly as effectively as winglets do. Wind tunnel tests have shown that winglets can reduce fuel use by at least 6.5%, since planes won't need as much thrust to fight drag. While that might not seem like a huge number, even a small decrease in fuel consumption leads to huge savings in costs when considering just how many miles airplanes are traveling each and every day.

Winglets are not without their drawbacks

Winglets can offer other benefits as well, such as improving aircraft stability, which slightly reduces turbulence. They're also better for the climate, as more fuel efficiency means less carbon emissions. However, there are some drawbacks to the design. Winglets are all about boosting lift, not airspeed. Because they add extra weight to the plane, it affects cruising speed. Longer flight times increase fuel consumption rather than reduce it, and are an important factor when it comes to logistics.

Winglets also add time and money to the designing phase and construction of new planes. The innovation of blended winglets, which smoothly curve up from the wing, reduced these production costs and led to many airlines adopting the design in the 1990s. The Gulfstream II, which was usually used as a private jet, was the first aircraft to widely adopt blended winglets. However, winglets don't offer as much benefit to larger planes that make long-haul flights where cruising speed is extremely important.

That's why they're more common on smaller and medium-sized planes and why you won't find them on large aircraft like the Boeing 777. Newer models, like the 777F, use raked wingtips rather than winglets, which are more fuel efficient while cruising. Another downside to winglets is that — because they are the thinnest, smallest part of the wing — they are especially vulnerable to severe turbulence and have the potential of falling off during flight. This is extremely rare, however.

Airlines continue to look for other ways to design more fuel-efficient aircraft

While winglets have saved countless gallons of jet fuel over the past few decades, you could always save more. If there's a way to reduce costs, you can bet that major airlines are actively trying to figure out how. Airbus introduced its own refined winglet design, called a sharklet, in 2011. In addition to raked wingtips, Boeing also employs split-scimitar winglets, which can be found on the 737 MAX. The company was also the first to use folding wingtips on a commercial aircraft, which allows the newer Boeing 777X to have larger, more fuel-efficient wings in the air, but smaller airport-compatible ones on the ground.

Of course, the most fuel-efficient airplanes would be ones that don't burn jet fuel at all. It's entirely possible that electric airplanes will be the future of flight. EVs on the road have exploded in popularity as battery technology and infrastructure have become more conducive to everyday use, but those are still major hurdles preventing electric airplanes from replacing their traditional counterparts. Batteries need to become a lot lighter and energy-dense before a commercial electric plane is truly feasible.

This hasn't stopped companies from trying, though. There are already smaller electric planes that have taken flight, including solar-powered airplanes that are truly climate friendly. If these ultramodern, outside-the-box aircraft became affordable to mass produce and maintain, it would be one of the biggest advancements in aviation technology ever. But, as winglets have shown, even small innovative designs can have large impacts on commercial flight.