10 Worst Accidents Recorded In Space Exploration History, And Why They Occurred

The story of Laika, the first dog in space, feels like the beginning of an inspirational biopic. She began as a stray in Moscow and was lovingly given the name Kudryavka(Russian for "little curly one"). After weeks of intensive training in confined, loud, shaking flight simulators, she proved to be the best candidate. She became the sole inhabitant on one of the most important satellite launches in history, Sputnik 2 in 1957, and made history orbiting Earth. What most people aren't aware of is Laika's tragic ending. No plan had been made to bring her back, and according to Malashenkov, she likely died from overheating in the capsule. Case in point: the history of space flight is rife with tragedy, but sometimes tragedy is a cruel prerequisite to progress.

Most people know about humanity's greatest successes, like the moon landing. Few know about the many deaths of pilots, astronauts, and animals. Today, we're taking a close look at 10 of the worst space exploration accidents. Instead of focusing solely on the loss of life to determine what is worst, we'd like to take a two-pronged approach here. One, to show how awful accidents often led to learning vital lessons that save future lives, and two, the cost of lies, secrecy, and corner-cutting.

The Nedelin catastrophe — Baikonur Cosmodrome

The history of ICBMs, which stands for Intercontinental Ballistic Missile, is closely tied with the history of spaceflight since they both hinge on rocketry. Modified ballistic missiles were actually what powered early spaceflights like Sputnik and Explorer 1. Soviets started working on a new R-16 standard in the late '50s and tasked Soviet Strategic Rocket Forces' Marshal Mitrofan Nedelin with making it happen.

Nedelin rushed to complete the project before the Bolshevik Revolution anniversary on November 7th as a sort of present for Khrushchev and a show of pride to the world, despite countless technical issues. Crews placed the rocket on the fated Sorok Pervaya Ploshadka (Site 41) launchpad on October 21st, 1960, at the Baikonur Cosmodrome, modern-day Kazakhstan. Per safety protocol, Nedelin should have evacuated the area, but around 150 personnel remained. When the pumps stopped working (one of many remaining issues), proper procedure dictated that they drain the fuel and then do repairs, but Nedelin ignored this. Then, one technician reset an improperly configured system, and disaster struck.

A chain reaction caused a series of massive explosions and a blast visible miles away. Many, including a half-dozen Soviet officials, lost their lives. Official Soviet counts put it at 92 deaths, but recent investigations say it's at least 122. Due to the Soviet culture of national pride, secrecy, and blame-shifting, hundreds of lives were lost in the Baikonur Cosmodrome (including Nedelin) and swept under the rug. It wasn't until Gorbachev's perestroika and glasnost (rebuilding and transparency) that the USSR publicly admitted to Nedelin's catastrophe in 1989, almost 30 years later.

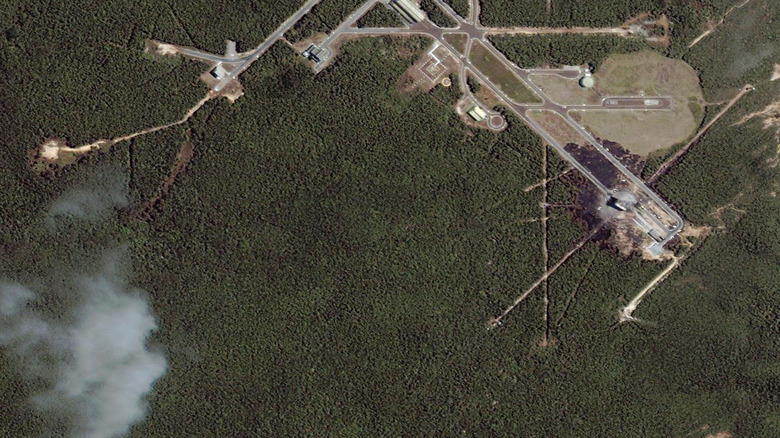

VLS-1 V03 rocket accident — Alcantara Launch Center

It's all too easy to talk about U.S. and Soviet Union space exploration, plus a few international collaborations, and forget other players — like Brazil. In 2003, Space Today Online explained that Brazil was on track to become Latin America's first nation to put satellites in orbit. Deep in the jungle, Brazil's Alcantara spaceport is perfect for rocket launching thanks to its location near the equator. The U.S., Russia, and others have set eyes upon Alcantara for their own launches. Brazil earmarked 2003 as the year the brand new VLS-1 V03 would carry two Brazilian-made science satellites to the skies. Previously, the VLS-1 V01 and VLS-1 V02 had failed, so everything was riding on the VLS-1 V03.

Sadly, the VLS-1 V03 never even lifted off. Fire broke out on one of its boosters, and it exploded then and there, destroying the launchpad and killing 21 people. According to the official investigation, it was likely due to the A-booster going off prematurely and electrostatic discharge lighting up the fuel.

A recurring theme you will see in this article is how disasters in space exploration often have positive effects. In the preface of the investigative report, officials called the event a powerful diagnostic tool for making their operations safer moving forward — proof that even the worst disaster can lead to good things. By 2016, the VLS program was canceled in favor of the newer VLM.

Space Shuttle Challenger — STS-51L Mission

In January 1986, the crew of the Challenger space shuttle took off from the launch pad on their STS-51L mission to deploy a satellite and study Halley's Comet. About 73 seconds later, 46,000 feet above the Atlantic, the Challenger exploded due to a fatal flaw. Although devastating enough because all seven passengers perished, the event was made all the more horrific by the fact that it was televised live and because a high school teacher for Reagan's new Teacher in Space Project, Christa McAuliffe, was lost to the disaster. Even today, almost 50 years later, the video is bone-chilling.

NASA has a detailed write-up explaining exactly what happened. From the get-go, there were countless delays and technical issues. In flight, the primary cause was the failure of the O-rings in one of the rocket boosters, exacerbated by cold weather. Then, a chain reaction of events set the hydrogen fuel alight and broke apart the rocket.

A detailed investigation known as the Rogers Commission Report determined that management pushed ahead with the launch despite cold weather that could erode the seals. The astronauts on board had no idea that launch day was concerningly cold, and no one on the ground knew something was wrong until the Challenger exploded. Forbes suggests NASA was under pressure, particularly to make the Challenger liftoff a show of pride before the president's State of the Union.

Space Shuttle Columbia — STS-107 Mission

The Columbia disaster doomed the space shuttle and is something of a dark echo of the Challenger event since it also cost the lives of seven astronauts, although the space shuttle broke apart upon return, not at launch. The crew of the Columbia left Earth on the STS-107 mission in January 2003, staying above the earth for 16 days. They brought with them the SPACEHAB Research Double Module, basically a portable miniature international space station (ISS) attached to the shuttle, wherein the astronauts could work in shifts around the clock to conduct dozens of experiments. It was mission success until the shuttle came in for Earth reentry. CAIB (the Columbia Accident Investigation Board) explains in great detail what happened.

As the shuttle was being launched, a piece of foam weighing only 1.7 pounds broke off and struck the wing. Upon re-entry, this damaged wing was exposed to temperatures over 5,000 degrees Fahrenheit. What followed was a domino effect of structural damage that eventually caused the wing to snap off entirely and the whole shuttle to disintegrate.

CAIB blamed this squarely on NASA's so-called broken safety culture, a combination of tight schedules, high pressure, limited budgets, and understaffing. NASA knew about the problem of shedding foam hitting previous crafts after launch, but it appears not to have made the proper effort to resolve the issue. Despite being the second tragic shuttle loss in under 20 years, there was a curious incident where support for the space program remained high after the fact. Future shuttles were improved. What's sad is that the Columbia was the first space shuttle in 1981 and ended up being one of the last, given that the program ended in 2011.

Apollo Command Module preflight test — Apollo 1 mission

Seeing Apollo named on a list of space disasters, one immediately thinks of the Apollo 13 "Houston, we've had a problem" mission that was made into a movie. Prior to Apollo 13, however, the very first Apollo mission suffered a devastating blow before it even got off the ground. On January 27, 1967, three astronauts of the Apollo crew — Gus Grissom, Ed White, and Roger Chaffee — were conducting a pre-flight test with the Apollo Command Module on its Saturn 1B rocket, just like a real launch.

There were countless delays, system malfunctions, and frustrations. Suddenly, a short circuit inside set the cockpit, filled with pure oxygen, on fire. As the astronauts panicked, it quickly became apparent that escape was impossible due to a complicated inward-opening hatch that took the people outside five minutes to open. All three astronauts lost their lives in the blaze. Apple TV+'s "For All Mankind" has one of Hollywood's limited fictional depictions of this incident.

While terrible in every possible way, there was light at the end of the tunnel. NASA realized it wasn't being imaginative enough in all the many ways things could go wrong, William H. Gerstenmaier told an Apollo remembrance ceremony in 2007. To be fair to NASA, space exploration at this time was in its infancy, and the Apollo 1 incident was a tragic growing pain that would prevent even more catastrophic losses. After 18 months of work, NASA completely redesigned its hatches to be easier to open and made a great deal of their material flame-proof.

Soyuz 11 — Salyut space station disaster

When we think of space stations, we think of the ISS and astronauts performing basic everyday tasks in zero gravity, like washing themselves with floating globules of water. But before the ISS, Russia and the U.S. wanted their own separate stations. Russia's Salyut (quite literally "salute") beat NASA's Skylab into orbit in 1971. That same year, the Soyuz 11 crew went up to the Salyut for 24 days. By all accounts, it was a successful mission with no hiccups. The cosmonauts worked hard conducting experiments, observing their bodily functions, and learning important lessons about life in space. They recorded their activities and transmitted them back to Earth, where Soviet citizens watched on TV. Cosmonaut Patsayev even celebrated his birthday. It was a mission of firsts, making it all the more tragic that it ended only after they left the station.

About 30 minutes before they would land, according to NASA, explosive bolts meant to separate the Soyuz into its modules also accidentally opened its pressure equalization valve — killing all three cosmonauts (who weren't in spacesuits) due to suffocation. The grimmest part of the story is that no one on the ground knew something had gone wrong. Automatic systems landed the Soyuz in Kazakhstan, and it was only upon opening the hatch that Soviet officials realized what had happened. They are the only cosmonauts (or astronauts) who have died in space.

Once more, hard lessons were learned from this event. Cosmonauts would no longer go without spacesuits when taking off or landing, and the Soyuz would get a complete overhaul. Both Soviets and Americans mourned these deaths, and a memorial was erected in their honor.

Soyuz 1 — Soyuz 1 docking to Soyuz 2 mission

Soyuz is something of an alter ego to NASA's Apollo. Today, it continues as a critical transport spacecraft to get astronauts to the ISS, since NASA no longer has its shuttles — making the delay of the Boeing Starliner spacecraft even more awkward. Soyuz's first mission (Soyuz 1) took place in 1967 with the goal to launch Soyuz 1 and 2 separately, have them meet in orbit, swap crews, and touch down. Vladimir Komarov was to go on Soyuz 1 with Yuri Gagarin (the first man in space) as his backup. However, almost none of this went to plan, as Robert Krulwich recounts via NPR.

Problems cropped up from the very beginning when an inspection revealed over 200 severe issues with the Soyuz 1 craft. Both Komarov and Gagarin knew that if they stepped into it, they would not return. Despite this, Soviet officials were adamant that the craft launch on schedule in commemoration of the 50th anniversary of the Communist revolution, and the Soviet's top-down hierarchy kept the information that the Soyuz 1 was not fit for flying from reaching top brass. In short, the writing was on the wall before the Soyuz 1 even hit ignition.

Komarov went to spare Gagarin (a national hero and his friend) a terrible fate. The series of events that followed was a chain reaction of failures. Parachutes failed during the descent phase, and Komarov cursed his superiors over comms as he plummeted to earth and died on impact. While NASA was suffering dearly from its poor safety culture, the Soviets were suffering from their national pride and secrecy. One could say it's the worst accident in space exploration history because it was entirely avoidable.

Valentin Bondarenko training accident — pressure chamber experiments

Another consequence of Soviet secrecy is that the world would often only find out about disasters, or the truth behind them, years after they happened. Valentin Bondarenko is one example of this. Ukrainian-born Bonderanko graduated from the Higher Air Force School as a Second Lieutenant and had been in cosmonaut training for a year before his untimely death at 24 in 1961. Some theorized that he could have been the first man in space instead of Yuri Gagarin. At the time, he had been conducting an isolation test in a sealed decompression chamber filled with pure oxygen to mimic a spacecraft — a situation eerily similar to the Apollo 1 incident mentioned earlier.

Similar to Apollo 1, all that was needed was one little spark. That spark was Valentin accidentally discarding some alcohol-soaked cotton wool onto a hot plate. He caught fire, and it took many long seconds for the airlock to cycle before he could be pulled out. In his last words, he assured everyone that his death was his own fault. No one knew about the death of this young Soviet cosmonaut until 1986, 25 years after the incident.

What makes this one of the worst accidents was the fact that his death, like that of the three astronauts on the Apollo 1, was what made the Soviets realize they should stop using pure oxygen atmospheres and flammable materials. Yet, no one knew about Bondarenko. Even Yuri Gagarin, the Soviet Union's national hero, received recognition despite the suspicious circumstances of the plane crash that killed him. It is tragic because a Soviet youth who had dedicated himself to space exploration was swept under the rug of history despite his complete sacrifice.

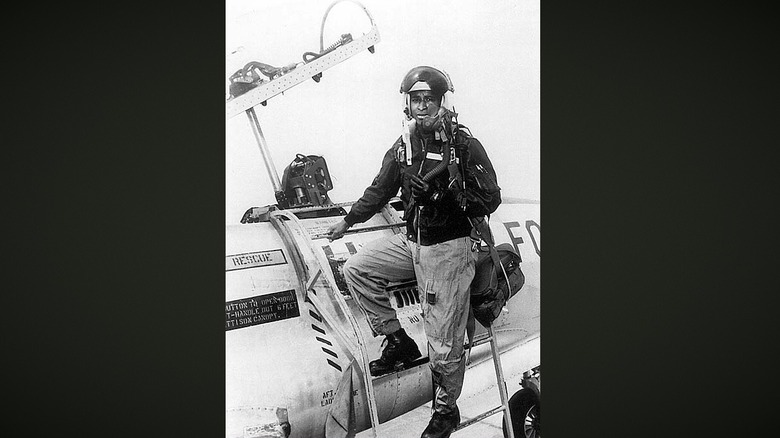

Robert Henry Lawrence Jr. — training jet crash

Major Robert Henry Lawrence, Jr. is a man that few will have heard of, but who nonetheless deserves remembrance. In 1967, he was the first black astronaut and a Vietnam combat pilot with 2,500 logged flight hours who started out in a Chicago slum and worked his way up to a doctorate. He'd trained pilots in West Germany and worked as a research scientist in New Mexico. Becoming an astronaut during the space race at 31 years old was no easy feat — especially during the racially charged civil rights era.

Lawrence was assigned to the Manned Orbiting Laboratory (MOL) program, a top-secret project in tandem with the United States Air Force to create a low-orbit station to get satellite imagery of the U.S.'s enemies, according to NASA. Ultimately, MOL was cancelled due to severe delays, a bloated budget, and eventual obsolescence thanks to unmanned spy satellites. Still, Lawrence's selection was progress since before him, astronaut candidate Edward Dwight Jr. in 1963 had allegedly not been allowed to train due to political considerations surrounding his race.

Later that same year, Lawrence was piloting an F-104 Starfighter in California for routine training with Major Harvey Royer. The F-104 Starfighter was often referred to as a missile with a man in it because of its sleek design, which allowed it to hit speeds of up to Mach 2. Sadly, this was to be his last time in the cockpit. He crashed into the runway, and only Royer survived.

Intelsat 708 disaster — Xichang Satellite Launch Center

Even before big private spaceflight companies like SpaceX, Russia and the U.S. weren't the only ones taking satellites to the big up there. The People's Republic of China was also a player. In 1996, they partnered with IntelSat — one of the largest commercial satcom providers — to launch its 708 satellite. At the time, according to Smithsonian Magazine, NASA had put a moratorium on servicing commercial payloads after the Challenger disaster. This created a vacuum in the commercial spaceflight industry for countries like China. But China's experience here was iffy. Its safety measures appeared to be insufficient, and its rockets already had a questionable record. The Long March 2E launch had ended in disaster in 1995.

On February 15th, the next-gen Long March 3B took off with its Intelsat 708 payload, immediately veering sideways to fly horizontally before crashing into a nearby hillside and exploding with the equivalent of between 20 and 55 tons of TNT (via GovInfo). This destroyed a nearby village and took the lives of at least six people. The problem here is similar to the Soviet Union: government secrecy. The People's Republic of China took charge of the investigation, covering up actual casualties and damages. The village, eyewitness Bruce Campbell recounted, is no longer there today, nor is there a memorial or a mention in the Chinese press. It's possible that hundreds could have died, making it the greatest disaster in space exploration, period, but we may never know the full scope of it.