A New Antarctica Map Reveals What May Actually Be Under The Ice - Here's The Unexpected Tech Behind It

It's common knowledge that Earth's southernmost continent, Antarctica, has exceptionally cold temperatures. However, you might not know the scope of the continent's frigidity. Antarctica is one of only two places on the planet almost completely covered by ice sheets, with Greenland being the other. The Antarctic ice sheet covers about 98% of the continent's land mass, and its ice is estimated to be about 1.2 miles thick. That means that if you ever visited Antarctica and took a step onto it, you'd technically be standing 1.2 miles above the actual continent.

Naturally, the land beneath that massive sheet of ice is of great interest to the scientific community, both for its own sake and for the data we could glean about climate change and ocean levels. This is why glaciologists have spent decades trying anything and everything to get a better look at it. Those long decades of work have gradually given rise to a new virtual map of the Antarctic continent, the most detailed look below the ice we've ever had.

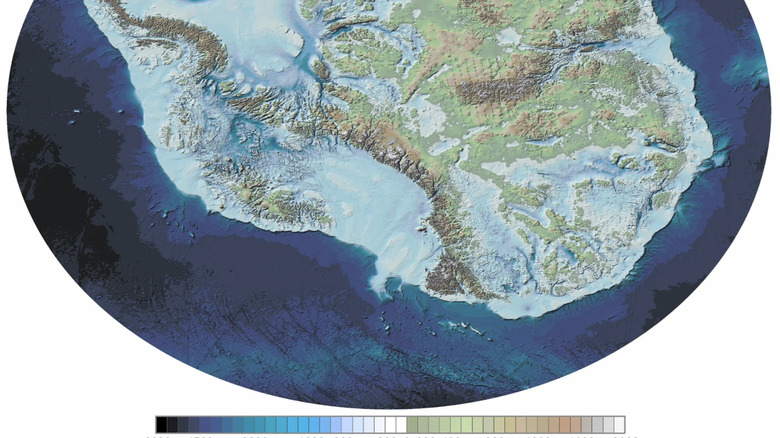

The product of a new study led by researchers from the British Antarctic Survey and published in Scientific Data, this incredibly vivid map of the actual topography of the Antarctic continent is known as Bedmap3 — the third major iteration of efforts to map the bed beneath the Antarctic ice.

Bedmap3 uses over 60 years worth of data to assemble a map

Bedmap3 was painstakingly assembled from more than 60 years' worth of data collected by researchers all over the world. It's made up of over 50 million data points, gathered from every conceivable means of exploring into and around the sheet. These include scans from satellites and 84 new surveys by specialized planes flying over Antarctica, as well as local research from exploratory ships, and even researchers crossing the ice sheet on dog sleds.

The map gives us a remarkably clear view of the bed, including frozen mountains and canyons. Besides generally interesting in its own right, this information is also a vital component of ongoing climate research. "This is the fundamental information that underpins the computer models we use to investigate how the ice will flow across the continent as temperatures rise," the study's lead author, Hamish Pritchard, told Phys.org.

As global temperatures rise, Antarctic ice will gradually start to loosen and fall into the ocean. With Bedmap3 as a guide, researchers can determine which parts of the sheet are likely to fall into the ocean, as well as precisely how much of it. This, in turn, will help them make estimates on rising sea levels. "Some ridges will hold up the flowing ice," Pritchard said; "the hollows and smooth bits are where that ice could accelerate."