How Astronauts Perform Basic Everyday Tasks In Zero Gravity

Thanks to not-so-recent advances in technology, we can shoot just about anything into space, or at the very least into Earth's orbit. At first, we launched spy satellites during the Cold War, but once we learned how to get people up there, we had to learn about space's effect on the human body and physics.

Everything we do on Earth, from exercising to sleeping on a bed, utilizes gravity to some degree. We essentially take gravity for granted, but that's understandable because we literally evolved to do so. But once we leave the planet, we experience what is known as zero gravity – technically microgravity since most astronauts are caught in a permanent state of free fall — but the result is the same. Outside of Earth's grasp, the laws of physics that we grew up with essentially fly out the window. Daily tasks on spaceships and the International Space Station (ISS) only somewhat resemble their earthly counterparts due to a lack of gravity, so astronauts needed to invent new ways to carry them out day after day.

If you want to learn about all the trials and tribulations astronauts go through to do something as seemingly simple as sleeping or cutting their hair, continue reading. Consider this a teaser of things to come should humanity ever plan to colonize other planets or visit distant stars.

Eating

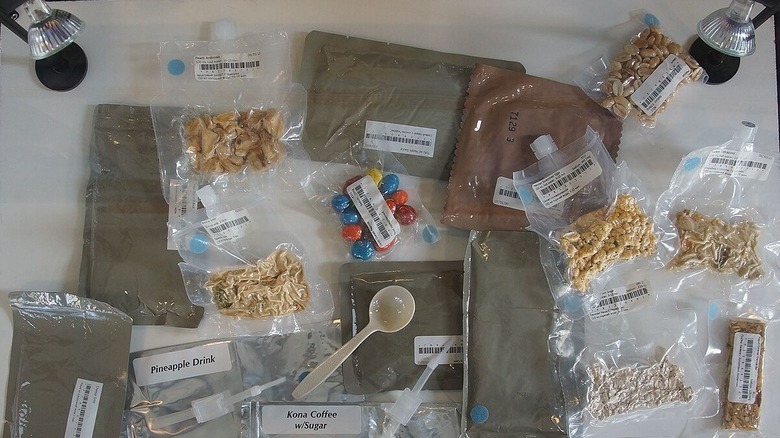

While food is crucial to life, NASA has only recently started experimenting with growing plants in outer space. Until we master the art of farming in zero gravity, astronauts will be limited to the foods they bring and those that are shipped to them, and those foods have their own sets of limitations.

The diets of astronauts have evolved alongside the technologies used to prepare food. One of the first hurdles scientists tackled was the question of whether eating was even possible in outer space. Thankfully, former astronaut and U.S. Senator John Glenn was the first spaceman to demonstrate that swallowing food wasn't dependent on gravity. Once the safety of eating in zero gravity was solved, astronauts started eating pureed and dried food pounded into cubes. Later, astronauts moved on to freeze-dried meals.

Today, outer space meals come in a wide variety of, well, varieties. Previously, astronauts heated up food with hot water, and while some foods still require some water to become edible, now astronauts can use convection and microwave ovens to cook meals. However, certain food offerings are absolutely banned for astronauts due to the lack of gravity. Anything that creates crumbs, such as bread and chips, is forbidden since a free-floating particle can slip into electronics and cause all sorts of problems. However, as of 2019, astronauts in the ISS started baking special cookies, so with some luck, certain food restrictions will be lifted in the future.

Drinking

Most students learn about the different states of matter early in their education. Plenty of people know that a liquid is defined as a material with no inherent shape but a definitive volume. However, that only applies to liquids when subjected to the effects of gravity. In space, liquid behaves differently and must therefore be imbibed differently.

Without gravity, water tends to float around as listless globules. To prevent water from accidentally entering sensitive equipment, potable liquids are stored in sealed pouches and sucked out via straws — think about how Capri-Suns work and you should get the right idea. Coffee functions the same way, and while many astronauts still use pouched caffeine, some can enjoy the tactile feeling of drinking coffee out of a cup. Astronauts recently invented a special mug that uses surface tension to keep coffee inside no matter which way the cup spins. But where does all this water come from? Not from Poland Springs, unfortunately.

Since astronauts in space shuttles and the ISS are cut off from standard sources of water, they must rely on more creative sources of liquids. And by creative, we mean disgusting. According to reports, much of an ISS astronaut's sweat and urine can be repurposed into drinkable water. The space station achieves this feat through a combination of a urine treatment system and dehumidifiers that capture moisture from breath and evaporated sweat. Also, all water is sent through a brine processor to flush out any urine brine that isn't captured the first time. Without these systems, astronauts would require daily deliveries of bottled water.

Sleeping

Human sleep schedules tend to figuratively and literally revolve around the sun. When the sun is in the sky, our body tells us to stay awake, and when the sun sets, our internal clock screams at us to fall asleep. Some alarm clocks replicate sunrise to try to help users feel rested, but relying on the sun for your circadian rhythms isn't possible when you go into space.

The ISS orbits around the Earth once every 90 minutes. That's about 16 complete orbits every day. To sleep through the constant sunrises and sunsets — as well as the space station lights that stay on all the time — astronauts don eye masks. Earplugs are also available to drown out the station's air conditioning and other electric devices. Astronauts in the shuttles use similar accommodations. Furthermore, everyone is allocated eight hours to get a good night's sleep, but they usually get closer to six.

You're probably wondering how astronauts get comfortable while sleeping. Since there's no gravity in outer space, nobody needs a bed. However, astronauts still need to ensure they don't accidentally bump into sensitive devices while catching some zero-g Zs. Astronauts accomplish this by cocooning themselves in sleeping bags secured to walls, much like caterpillars anchoring their cocoons to sticks. Sleeping bags can also latch on to seats. Due to a lack of gravity, orientation doesn't matter so long as the sleeping bag and its astronaut don't go floating off.

Exercising

How much can an astronaut bench press? Trick question. It doesn't matter because weight doesn't exist in zero or micro gravity — no gravity means no weight. However, gravity also helps maintain our bodies, so exercise is paramount for astronauts so they can function when they return to Earth. This only sounds like a paradox until you realize that some exercises don't need gravity.

Workouts in outer space have evolved as technology has advanced. Early space mission astronauts had to rely on resistance bands (those colored elastic bands physical therapists give you), but they quickly moved on to bigger and more effective equipment. These included the Interim Resistive Exercise Device (IRED), which used flex packs — cylindrical aluminum outer rims with rubber spokes poking out towards a central hub that revolved around a metal axle — to provide up to 300 pounds of resistance.

Currently, astronauts stay in shape thanks to a piston and flywheel system called the Advanced Resistive Exercise Device (ARED), a treadmill, and a cycling machine known as the Cycle Ergometer with Vibration Isolation and Stabilization System (CEVIS). As if their schedules weren't busy enough, astronauts need to devote two hours to exercise every day. Missing even one session would exacerbate the natural loss of bone and muscle strength that occurs while outside of Earth's gravity. If not for the exercise regime, astronauts may be unable to walk when they land.

Bathing

As we established in a previous entry, water behaves differently in zero gravity, so you can't use it to take showers or baths as you would on Earth. Even if you could, water splashing everywhere would pose a danger to the space shuttle and the ISS instruments. The only safe way to clean in zero gravity is to remove as much water as possible from the equation.

Currently available technology influencing the techniques astronauts use has been a recurring theme throughout this article, and hygiene is no different. During the early Gemini and Apollo missions, astronauts washed infrequently with sponge baths. This strategy let them conserve as much water as possible, but also made them smell like something crawled up their space suits and died. Later, astronauts graduated to a shower tube that secured their feet to the floor while they sprayed themselves with a hose.

The modern iteration of space showers has taken a step back and more closely resembles the sponge baths of early missions. Scientists clean themselves with liquid soap, rinseless shampoo, and a dab of water that is quickly absorbed by a towel or a powerful nearby vacuum. Because of how water works in zero gravity, the suds stick to astronauts and are generally easy to mop up. However, a lack of gravity hasn't changed dental hygiene one bit. Astronauts still use a toothbrush and toothpaste, but unlike most Earthly toothpastes, these are safe to swallow. However, some astronauts elect to suction out the toothpaste or just spit it into a towel.

Cutting their hair

When you visit a barber, someone always has to clean up after your appointment. Time isn't of the essence since hair just sits on the floor until it is swept up, but without gravity, hair becomes a free-floating menace that has to be handled immediately.

For the most part, cutting hair in zero gravity works the same way as cutting hair on Earth ... as long as you rely on clippers instead of scissors, that is. Astronauts use a set of special clippers with a vacuum attached to the business end. As soon as the clippers shave off hairs, the vacuum suctions them up and out of sight. However, sometimes the device misses a few cuticles. These rogue hair scraps generally float towards vent ports and get caught in them. While these hairs can accumulate over time, the ports are cleaned with enough regularity that they don't cause a problem.

While the above-mentioned system works great on head hair, astronauts who want to get rid of facial stubble utilize a much more low-tech method — they just use a regular razor. Granted, astronauts pair it with a specially designed shaving cream that makes the whiskers cling to the razor and then wipe it off with a cloth. Otherwise the process is exactly the same as it is on Earth. Bushier moustaches, however, require the clipper/vacuum duo due to the sheer volume of hair.

Going to the bathroom

Everyone needs to use a toilet sooner or later, and an entire industry is devoted to kitting up bathrooms. You can buy plenty of bathroom gadgets, and depending on where you go, you can find some of the most high-tech bathrooms in the world. However, they have nothing on the bathrooms astronauts use because Earth toilets still rely on gravity.

Early astronauts were asked to go in their space suits – even when they didn't include functioning urine collection systems. However, NASA quickly learned that toilets were preferable to adult diapers. Today, space toilets rely on suction to prevent waste from potentially floating around in zero gravity. This modern device is essentially split into two parts. To go number one, astronauts attach a funnel and hose to their business area and start going. The hose suctions up everything without spillage. But if they must go number two, they just open the toilet and let another vacuum suck up all the waste and stench.

Of course, this system raises the question of what happens to bodily waste afterwards since space shuttles and stations don't exactly have sewer systems. Well, as previously stated, urine is recycled and purified to be used as future drinking water. Stool, however, is collected in garbage bags that are then sealed in airtight containers. These are then loaded into ships and allowed to burn up in the atmosphere. Nevertheless, some samples are freeze-dried and sent to laboratories on Earth for testing. The less you think about it, the better.

Writing

Many sci-fi stories hinge around the concept of scientific exploration. It was literally the opening narration of early "Star Trek" episodes. And when you conduct research, you have to take notes. While characters in "Star Trek" use tablets for note keeping (one of the many technologies the series predicted accurately), real astronauts have to rely on more mundane means.

Astronauts have been using a device known as the Fisher Space Pen since 1968. This pen was specially designed to work in zero-gravity environments by using pressurized nitrogen to expel ink. Not only can the pen write at any angle, but it can withstand an intense range of temperatures. Unlike most technologies invented for astronauts, the Space Pen is readily available for use on Earth. However, they are far more expensive than the average gravity-dependent pen, which is indicative of the item's almost $1 million development costs.

By now, you're probably wondering why anyone spent so much money on pens that could work in space. Why not use pencils? Well, the same reason you can't eat saltines in the ISS. Pencil graphite (previously lead) tends to break off while in use. This isn't a problem on Earth thanks to gravity, but in outer space, these shards can float away and get lodged in sensitive equipment. Even the writing implement of choice for Soviet cosmonauts, grease pencils, suffered from this problem, albeit with wax. However, thanks to the advent of handheld computers and tablets, astronauts have even more high-tech annotation methods.

Going outside

The dark secret of outer space is that there's no air out there. That's why astronauts have to wear space suits when they exit shuttles and space stations. However, contrary to popular belief, going for a space walk isn't as simple as putting on a space suit as if it were a down jacket.

Every time an astronaut has to exit a space station or shuttle while still in the cold vacuum of outer space, they have to undergo a lengthy decompression process. This consists of a 140-minute regimen of intense exercise and breathing pure oxygen, all while the air pressure in the airlock slowly decreases. Of course, the astronaut must put on their pressurized space suit during this process. And once they return from their spacewalk, the astronaut has to undergo a similar repressurization process.

If an astronaut doesn't properly follow the depressurization and repressurization protocols, or worse doesn't follow them at all, they risk getting decompression sickness, also known as the bends. This isn't an actual sickness, but a potentially fatal event where nitrogen bubbles form in the body when moving too quickly between areas with significantly different air pressures. In the best case scenario, the bubbles form in a non-vital area and only cause minor joint pain or numbness in the extremities. However, decompression sickness has been known to create bubbles in arterial blood streams, which can cause embolisms that result in strokes. Pressurized suits are essential for surviving in outer space, but proper decompression and recompression practices are crucial for returning to the ship safely.

Breathing

Since we can't farm in outer space, we can't grow air-producing plants in space stations. This raises the question of how astronauts maintain a constant supply of oxygen. The solution, as with many things in life, was created through the power of science.

Instead of relying on air canisters, astronauts in the ISS produce their own oxygen using two systems. The first is a process known as electrolysis, during which electricity generated by a space station's solar panels splits stored water into hydrogen and oxygen. The oxygen is pumped into the station for astronauts, while the hydrogen is reserved for other systems. However, some sources claim that the hydrogen is discarded and blasted into space. But this is only half of the equation since humans exhale carbon dioxide, which can prove dangerous in high concentrations.

Normally, we rely on plants to convert carbon dioxide into breathable oxygen, but again, you can't really bring plants up into space (yet). So how do astronauts prevent themselves from choking on their own carbon dioxide? Every modern spacecraft and space station is equipped with canisters full of lithium hydroxide. When carbon dioxide is sent through the canister, it joins with the compound to create lithium carbonate and water. Since the space station and shuttle systems are designed to recycle as much water as possible, the water produced by the lithium hydroxide canisters is used for a variety of purposes, including drinking and another round of electrolysis. Currently, the ISS is also experimenting with another carbon dioxide removal system that utilizes potassium superoxide instead of lithium hydroxide.