The First Electric Car Is Older Than You'd Realize (And It Looked Stunning)

There is little doubt that electric vehicles (EVs) will have a significant place in the future, but what's less known is that they also had a place in the past. During the 19th century, pioneers like Karl Benz, Gottlieb Daimler, Samuel Brown, Jean Joseph Étienne Lenoir, and others harvested the fruits of the Industrial Revolution by creating vehicles powered by steam and internal combustion.

These early rudimentary creations were scarcely superior to tried-and-true horsepower (the original kind), but visionaries saw a place for them in the future. One of the first practical cars ever invented, Benz's Motorwagen, took its first public drive in Mannheim, Germany, in 1886. Steam had been a viable power source in locomotion for as much as a century before the Motorwagen, and internal combustion dominated personal vehicles in the 20th century. But long before Tesla Motors, Rivian Automotive, and Zero Motorcycles, electrically powered vehicles were in a fierce competition for prominence in the automotive industry.

The technology behind EVs goes back further than most imagine, and it set off a race to see which power source would unlock the personal vehicle's world-altering potential. Much of the EV story is yet to be written, but join us as we cast back into history to uncover the story of the first electric car.

Humanity harnesses electricity

Electricity is a phenomenon found in any number of nature's processes. Outer space is fundamentally electric. Lightning strikes may have been the reason humanity gained control over fire. Electrical impulses race through our bodies, sending messages and transmitting critical responses.

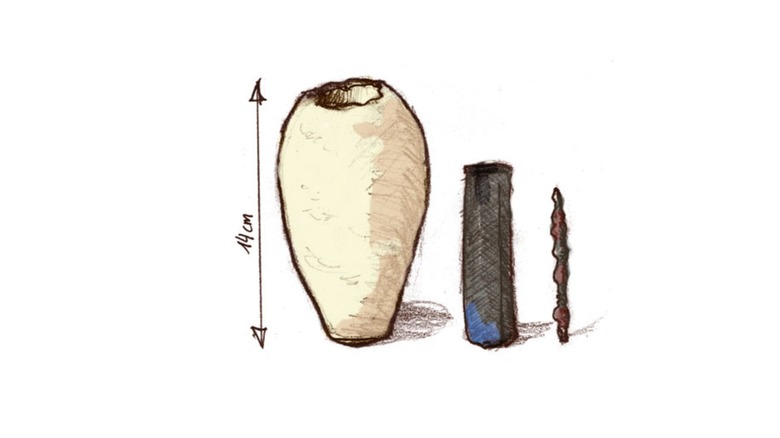

While many likely associate Benjamin Franklin's kite experiment with the discovery of electricity, the truth is that far older ancestors were well aware of its power. For instance, Ancient Egyptians practiced electroplating as far back as 4,300 years ago. And one of the most intriguing artifacts in the history of electricity is the device pictured above, discovered near Baghdad in 1936. The Parthian Battery was a clay jar filled with vinegar, featuring an iron rod sheathed in copper, capable of producing 1.1 to 2 volts of electricity — Some believe it could date back 2,000 years.

However, while the function of the Parthian Battery remains a subject of debate, the birth of the modern battery is well documented. In the mid-18th cenury, a stroke of parallel thinking led German inventor E. Georg von Kleist and Dutch scientist Pieter van Musschenbroek to independently develop the Leyden Jar, a device that could draw and store electricity when connected to an electrostatic generator. 50 years later, Alessandro Volta developed the first battery that could supply a steady source of electricity. Napoleon Bonaparte was so impressed he named Volta a count for his achievement. Today, we measure electricity in volts as an homage to the Italian physicist.

Electric power leaps to the automotive world

The 19th century was rife with experimenters reimagining travel using the technological marvels of the Industrial Revolution. Early batteries were not rechargeable, and voltaic piles were hardly suitable for use in a vehicle. But that didn't stop thinkers and tinkerers from pushing science forward.

Hungarian engineer Anyos Jedlik developed an electromagnetic rotator in 1827. With no other practical uses for the device, he used it to power a model locomotive. In 1832, William Sturgeon invented the first electric motor that could power a machine. Thomas Davenport patented a direct-current (DC) electric motor in 1837. The rechargeable lead-acid battery arrived in 1859 courtesy of inventor Gaston Plante. Galileo Ferraris developed an induction motor in 1885. The technology required to harness electricity drew together over thousands of years of history, but in the 19th century it must have felt like only a matter of time before someone built a fully fledged electric vehicle. And indeed, it was.

Scotsman Robert Anderson developed the first electric-powered vehicle between 1832 and 1839. Due to the technological limitations of the time, Anderson's design was impractical. The batteries were non-rechargeable, and the design was rudimentary, limiting the vehicle's range and usefulness. British builder Thomas Parker introduced a new generation of electric vehicles in 1884. He was an engineer responsible for electrifying London's subway system and developing an electric tram in Blackpool. As it was known, the Elwell-Parker used rechargeable batteries, which proved more practical and longer-lasting than any previous design.

Andreas Flocken

Not much is known about the life of the man who would combine these disparate pieces of emerging technology into the first mass-produced electric car. Andreas Flocken was born in Albersweiler, Germany, in February 1845, the perfect time for someone with a keen mind to take advantage of the incredible scientific advancements emerging from every quarter.

Gifted with a curious mind and an entrepreneurial spirit, Flocken secured early employment at a tractor factory. By the time he was 35 years old, he had his own business, which he used to exercise his mind and embrace new ideas. Based in Coburg, a small town in northern Bavaria, central Germany, Flocken couldn't help but attract the attention of the curious.

In 1888, Coburg's local newspaper reported on a curious contraption taking shape in Flocken's workshop. The erroneous reporter claimed it was a steam-powered vehicle. In reality, the two-person carriage would be powered by electricity.

The Flocken Elektrowagen

The populace must have been stunned when Andreas Flocken first pulled the divinely-monikered Elektrowagen into the streets of Coburg in late 1888. Steam-powered locomotives were commonplace by then. However, to the townspeople, the horseless carriage must have looked like it was pulled along by magic, or perhaps the invisible kestrels of "Harry Potter" fame.

Unlike the sputtering, spitting, and whirring steam vehicles some might have seen in person, the Elektrowagen moved along silently. The Elektrowagen enjoyed a maiden run that went well — until it didn't. After a two-and-a-half hour perambulation around the area, undoubtedly tipping his cap at gawking passerby, Flocken ran out of power over 15 miles from home near the village of Redwitz.

Built primarily of wood, with tall wheels, an iron chassis, room for two, and an electric motor powered by a lead-acid battery producing a solitary single horsepower, the Elektrowagen weighed 900 pounds and achieved a blistering maximum speed of 9 mph. Despite the successful maiden run, Flocken sensed opportunities for improvement. By 1903, the Elektrowagen had sub-axle steering, pneumatic tires, a rudimentary suspension, and electric lights. Unfortunately for Flocken, he had hitched his (non) horse to the wrong wagon, so to speak. Electric vehicles showcased ever-increasing promise until their inherent limitations turned the tables in favor of vehicles powered by internal combustion engines.

The EV trend takes off

Andreas Flocken and Thomas Parker's revolutionary proof-of-concept electrified the industry. Karl Benz, a direct contemporary of Flocken, unveiled his Motorwagen in 1885. Considered by many today to be the first car ever invented, that title belies the experimentation of those who went before, including Frenchman Nicolas-Joseph Cugnot's steam-powered tricycle dating back to 1769.

The Motorwagen and Elektrowagen firmly pulled the industry into the earliest stages of its modernity. Three potential power sources vied for supremacy, and it was anyone's guess whether steam, internal combustion, or electricity would win out. Technology improved, and innovation abounded as the 19th century drew to a close. Though Flocken had an excellent claim to the inaugural production EV, the reward for the first commercially successful one went to Philadelphia-based partners Pedro Salom and Henry Morris, who built carriages that could hit 20 mph on trips of up to 25 miles thanks to a pair of 1.1 kW motors — technology borrowed from electrified street trolleys. Not only did their invention outdo the Elektrowagen in performance, but it even gave its excellent name a run for its money, with the partners naming their contraption the Electrobat.

A who's who of early auto pioneers got in on the action. Ransom Eli Olds, later of Oldsmobile fame, dabbled in electric carriages. Dr. Ferdinand Porsche, the father of the man who founded the car company, developed a one-of-a-kind electric vehicle known as the Egger-Lohner C.2 Phaeton. Thomas Edison purchased an electric vehicle from a little startup later called Studebaker Automobiles. Unfortunately, the glory days would not last.

The fall of the electric vehicle

Early electric vehicles thrived through the end of the 19th century, and into the 1910s and 1920s. One, La Jamais Contente, even briefly held the title of fastest car in the world in 1899. They were clean, quiet, and powerful, but they suffered from a vital drawback that revolved around batteries as a power source — charging.

Electric vehicles were ultimately doomed in a world where gasoline was cheap and easy to get, and no one had yet coined the term climate change. The world's infrastructure wasn't ready for an EV revolution — some feel that's still true today. In the United States, one of the largest automobile markets, the issue revolved around the enormous distances between cities connected by an improving road system. Businesses that provided battery charging and changing services appeared alongside busy roadways. Recharging a lead-acid battery cost about 20 cents per kilowatt hour at a time when a gallon of gasoline only cost five cents. Ask any consumer which they preferred, and you'd likely have gotten a straightforward answer.

When Texas became a source of abundant crude oil, domestic gasoline proved inexpensive and plentiful. Entrepreneurs invested in building gas stations over the less-popular charging stations. An incomplete power grid would not tether travelers. A filling station would do the trick more effectively and less expensively. By the late 1920s, the writing was on the wall: The 20th century was the age of internal combustion.

EV renaissance

If circumstances hadn't been such that consumers and planners turned from electric vehicles in the early days, the world might look very different today. A century of development has proven nothing short of revolutionary in internal combustion. What might that same effort and expense invested into battery technology have wrought?

A new age of EV is rising from the ashes of the Flocken Elektrowagen and other progenitors. Purists and traditionalists decry the limited infrastructure and silent operation of modern electric vehicles, but even the oldest car brands in America are making EV batteries. Newcomers like Tesla and Rivian are bringing increasingly capable and inexpensive EVs to market. Some of the old arguments remain, namely the infrastructure issues, but it seems only a matter of time before those are ironed out. If humanity can crisscross continents with power grids, internet networks, and sewage systems, why not charging stations?

When Andreas Flocken pulled his Elektrowagen onto the street in 1888, it was unlikely that he could predict the path electric cars would take. Now, after a century of being derailed by internal combustion, the ancestors of the Elektrowagen are primed to inherit the earth.