10 Surprising Ways Racing Technology Has Made Your Car Better

They say necessity is the mother of invention, but what is the mother of improvement? How do you take a product and make it better? In the auto industry, innovative engines are often the answer. Sometimes, engineers will try to adapt the technology of one kind of vehicle for another. One famous example is the Chrysler Turbine car and its jet engine. Chrysler staff took the turbine engine they developed for World War II military vehicles and used it to create an all-new automobile powerplant. But not every innovation is engine-based. Sometimes, car manufacturers take ideas from one system in a car and use them to improve another.

While racing cars are powerful standalone vehicles in their own right, they also serve as testbeds and proof of concepts later adapted for general automobile use. Any technology that makes racing cars grip the road better or improve fuel efficiency can do the same for cars meant for the average consumer. While some technologies take center stage in a vehicle's design, others are more under the hood. Regardless of where the component is located, cars wouldn't be anywhere near as advanced as they are today if it weren't for racers who tried to push the limits of performance.

Here are 10 surprising ways racing technology has made your car better.

Carbon fiber makes things lighter

Carbon fiber is being used more often in a variety of industries. The material is used in applications as varied as airplanes, fishing poles, and prosthetics. However, we probably wouldn't know as much as we do about the material's properties if it weren't for a fateful race.

While sports racing cars have utilized carbon fiber since the 1970s, in 1981, McLaren produced a Formula 1 car, the MP4/1, made almost entirely out of carbon fiber. This car raced in that year's British Grand Prix and won, and it also participated in the Monza Grand Prix, although that time the MP4/1 crashed. Fortunately, the driver survived. Both events got audiences thinking about carbon fiber because while the victory demonstrated the material's lightweight properties, which helps improve car performance, the survived crash showed that it didn't sacrifice durability or driver safety.

Thanks to the MP4/1 and its racing performance, carbon fiber is a common material for car parts, especially in brands such as BMW, GMC, and Alfa Romeo. Virtually every automobile that utilizes carbon fiber has higher fuel efficiency than equivalent models with more mundane parts, although this usually comes at a higher manufacturing cost. Electric vehicles also use carbon fiber as a lightweight construction material in addition to components of high-voltage batteries.

While car manufacturers have yet to produce a consumer-oriented vehicle constructed solely out of carbon fiber, odds are when they do, the company will have one of the most fuel-efficient products on the market.

Push-button start revolutionizes ignition

Cars are now so advanced you can start them without a key. You still need a remote fob (which uses radio signals to disarm car alarms and locks) because car security is always important, but you start cars with the push of a button. A combination of the technologies even allows modern cars to start remotely. Adding remote start to your car can be costly, but a boon during the cold winter months. In truth, push-button ignitions have been around for far longer than most think.

Many race cars have ignition systems controlled by buttons. Depending on the setup, the race team may have to undertake a few steps before pressing the main ignition button, but no key or fob is necessary. One might assume that the lack of a key or other security features might make race cars easy to steal, but it's quite the opposite. Key ignitions streamline the startup process, but racing teams often have to manually perform a series of actions before it will work. One mistake renders the vehicle useless until you fix it.

Admittedly, modern push-button ignitions in consumer vehicles are less of an adaptation of racing car ignitions and more an evolution of the process. Consumer vehicle push-button ignitions streamline the ignition process and remove the need to fiddle with keys. If you have the fob, you can press the button and go. If anything, racing cars could take a page from consumer vehicles and adopt the radio signal-enabled key fob system.

Brakes become more effective

What's the most essential component in a car? Probably the brakes, because nobody would survive their first trip to drive a second time without them. While braking systems predate the earliest cars, the most common modern brakes became famous because of the racetrack.

Disc brakes are a braking system that squeezes a pair of pads against a rotating disc. The friction caused by this interaction slows down the attached shafts and wheels. An early patented instance of a disc brake was filed in 1902 by Frederick William Lanchester. However, this wasn't a new invention. Elmer Ambrose Cleveland invented a similar system in 1898, and Lanchester updated the design. However, disc brakes didn't catch on for at least half a century.

While disc brakes were used for airplanes, especially during World War II, in 1953, a Jaguar C-type racer utilized Dunlop-brand disc brakes. This vehicle participated in that year's Mille Miglia time trial. Two years later, the French car manufacturer Citroën started installing disc brakes in the front wheels of its consumer DS model. Triumph became the first British producer to add discs with its Triumph TR3 in 1956.

In 1993, a Jaguar XK with four Dunlop disc brakes won the Le Mans race, a grueling 24-hour test of speed and endurance. The benefits of disc brakes were clear, and now they are standard equipment on most modern consumer vehicles.

Dual-clutch transmission makes switching gears lightning fast

Automatic transmissions are a godsend for drivers as they streamline the process of shifting gears. However, many people still swear by manual transmissions, especially if they are dedicated race car drivers, so it's ironic that a common form of automatic transmission was invented for race cars.

As its name suggests, a dual-clutch transmission (DCT) drives gears via two internal shafts. One is hollow, and another runs through the hollow shaft. The hollow shaft is in charge of evenly numbered gears, while the interior solid shaft controls the odd numbered gears. Electronics and hydraulics shift between gears using dog clutches. The result is akin to using two clutches simultaneously, so drivers don't have to worry about power interruptions during gear changes.

French engineer Adolphe Kegresse conceptualized an early DCT in 1935. While his seed of his original idea didn't immediately bloom into physical form, Porsche adapted the concept for its 956 and 962 race cars, and Audi did the same for the Quattro S1, which competed in rally races in 1985. The first consumer car to utilize a DCT was the 2003 Volkswagen Golf R32.

Camshaft engines increase power

In car racing, speed is less the product of a powerful engine and more the product of an efficient one.

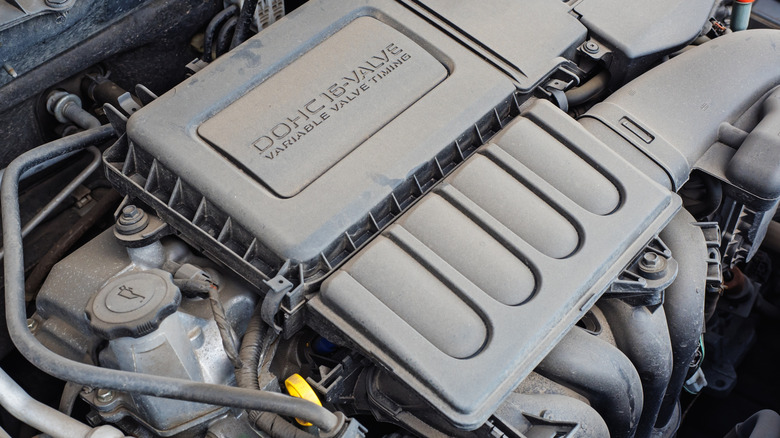

The overhead cam engine is a vehicle engine that places the camshaft above the combustion chamber, instead of below the chamber as with overhead valve engines. By altering the camshaft locations, overhead cam engines reduce the number of moving parts in the valve train, improving vehicle performance. Moreover, these motors come in two varieties: single overhead camshaft (SOHC) and dual overhead camshaft (DOHC). Whereas SOHC engines are less expensive to produce, DOHC engines provide more power.

The DOHC engine dates back to 1912, when French car manufacturer Peugeot hired Swiss engineer Ernest Henry. The company wanted to cram extra power into its race cars. Henry designed an engine that used two camshafts per cylinder bank instead of rocker arms, a crucial component in overhead valve (OHV) engines. Thanks to the DOHC, Peugeot won the 1912 French Grand Prix and 1913 Indianapolis Grand Prix, making it the first foreign car company to win the America-based race.

After World War II, other car companies started adopting Peugeot's DOHC design. The gas crises of the late-20th century added to its appeal. The DOHC engine's ability to squeeze more power out of less displacement allowed the technology to dominate the consumer automotive industry.

Spoilers glue a car to the road

Engine power is vital in a race, but a car that can't transfer as much power as possible to the road is useless. A tire needs to properly grip the asphalt to get the most out of an engine's torque, and the easy solution is to make the car heavier. But that option also slows the vehicle down. This paradox of performance was solved by adding fins to racing cars.

Odds are you've seen at least one car with a horizontal bar sticking out of its rear. It's not just for looks (sometimes). These rear spoilers really make a difference. Whenever wind hits the spoiler, the air shoots up, causing the spoiler to press down on the car. This is known as downforce, and the simulated weight allows tires to better grip the road without adding actual weight to the vehicle. The faster a car goes, the higher the downforce.

The origin of the spoiler can be traced back to the world's first rocket-powered car, known as the Opel RAK 1. Engineers wanted to prevent the vehicle from turning into an actual rocket, so they added wings to it to add downforce. However, these weren't spoilers proper. The Lotus 49 advanced the concept as one of the earliest race cars to successfully use a spoiler on the track.

Starting in 1968, the Lotus won 12 Grand Prix races, thanks partly to its spoiler. However, the Lotus 49's spoiler was much taller than modern day examples. Understandably, other racing car teams started copying the Lotus 49's design, but these towering tail fins were banned after several accidents. Modern spoilers are far more low-profile in comparison.

Roll cage/roll bar prevents driver deaths

A car's roof and doors are the first line of defense in a crash, especially if the vehicle flips over. If they stay intact, drivers and passengers have a much better chance of surviving. The faster you go, the more dangerous a flipping crash becomes, so it makes sense that people who push their cars to the breaking point pioneer ways to survive crashes at breakneck speeds.

Roll cages do precisely as they advertise. They are cages that protect drivers and passengers if a car rolls over. Sometimes, a roll cage is an optional add-on, and other times, it is integrated into the design of a vehicle. In the United States, roll cages fit into a legal gray area because they diminish the efficacy of crumple zones in consumer vehicles. However, roll cages are still a common sight in race cars, partially because that's where they originated.

The British race car driver John Aley is credited as the inventor of the roll cage's progenitor, the roll bar. He had experience with horrific race car accidents, both as a witness and survivor, that involved roof collapses in rollovers. Aley introduced the roll bar in 1970, and the Fédération Internationale de l'Automobile (FIA) — the governing body in charge of motorsports rules — enforced the use of roll bars one year later. The concept eventually expanded into the roll cages commonly found in performance and off-road vehicles today.

Suspension makes the ride smoother

A car's suspension is crucial to maintaining a smooth ride. If you don't regularly check and repair your car's suspension, it could literally shake apart. The general automobile industry's reliance on suspension systems started after a French car manufacturer won an important race, all thanks to a crucial component in modern car suspensions.

In 1902, the Mors automobile company became one of the first manufacturers to install an independent suspension. Most Mors vehicles were built with racing in mind, so this primitive suspension was designed to aid cars on the raceway. Shock absorbers allowed Henri Fournier to win the 1902 Paris-Berlin race. The company exited racing in 1908 and was purchased by Citroën and shuttered in 1925, but its innovation proved the value of suspensions in car performance and comfort.

Car suspension has evolved by leaps and bounds ever since Mors demonstrated the efficacy of shock absorbers. Shocks are only one part of an entire suspension system along with components like struts. While shock absorbers absorb vibrations and bumps in the road, struts aid steering and braking while supporting the car's weight. Mors and its shock absorbers predated many other crucial parts of suspension systems, but car suspensions might look different today without the company and its initial automobile dampers.

Seatbelts prevent ejections

Seatbelts are one of a car's most critical safety components, as they keep people secured to their seats during stops. Without seatbelts, sudden braking even at low speeds can cause injury. However, one of the most important iterations of seatbelts was designed for drivers going much faster than 25 mph.

Early seatbelts were quite different from what we recognize today. The British landowner Sir George Cayley invented the first seatbelt, although he designed it for airplanes instead of cars. Seatbelts weren't patented until 1885, when they became equipment for taxis.

The first big leap forward in seatbelt technology occurred in 1922. One version of the story has race car driver Barney Oldfield hiring a parachute designer to develop a racing harness for his Indy 500 car. However, some sources claim he bought a parachute harness and MacGyvered it to his vehicle himself to create a rudimentary seatbelt. Either way, Oldfield was inspired by seeing fellow drivers ejected from their vehicles during high-speed crashes, and his creative thinking may have saved lives.

Unfortunately, even after Oldfield used them, seatbelts took several decades to catch on. Many car historians believe the turning point came in 1959, when Swedish engineer Nils Bohlin invented the three-point seatbelt we recognize today. So while we can't credit Barney Oldfield for revolutionizing car safety, he still had a part to play.

Rearview mirrors increase driver awareness

The best way to avoid a car accident is to watch everything around you, including cars behind you. To this end, you need rearview and side mirrors.

The first recorded example of a car with mirrors was the 1906 Argus. However, a race car driver, Ray Harroun got people talking about rearview mirrors when he entered his custom car, the Marmon Wasp, into the 1911 Indy 500 race. In prior races, he relied on a co-driver who told him when to change lanes, but he couldn't do that with the Marmon Wasp because it was a one-seater. However, he still needed to know when it was safe to swap lanes, so he installed the world's first rearview mirror in his car. This add-on gave him a more expansive view of the racetrack and cut out all the co-driver weight from his vehicle. This lighter car with superior rear views resulted in Harroun winning the race.

While Harroun stated that his rearview mirror didn't do him much good because it kept bouncing around due to the brick race track, some inventors caught mirror fever. Elmer Berger patented the cop spotter, a side mirror that let drivers know if police were tailing them, in 1921. Despite this niche intent, the cop spotter caught on and normalized the use of mirrors to see more of the road while driving.