Can You Be Arrested Just For Joining An Outlaw Motorcycle Gang?

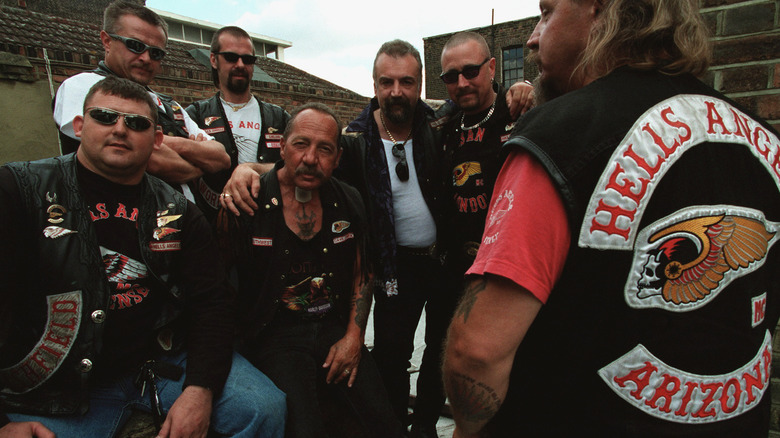

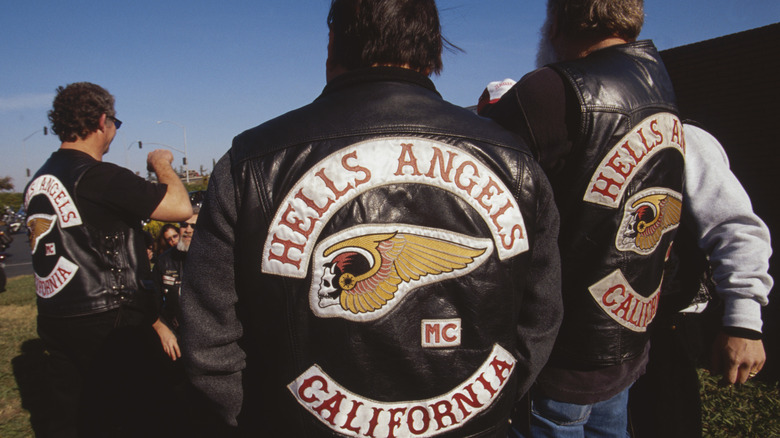

Outlaw motorcycle gangs are as much a part of the American criminal mystique as cowboys, bootleggers, and gangster rap. Born of the angst of World War II veterans acclimating to their new civilian lifestyles, they've grown from small social clubs into multinational criminal organizations. The Hells Angels' website counts 64 countries in which they're active. And although outlaw motorcycle gangs only account for an FBI-estimated 2.5% of American gang membership, they're disproportionally responsible for gang-related violence and drug offenses.

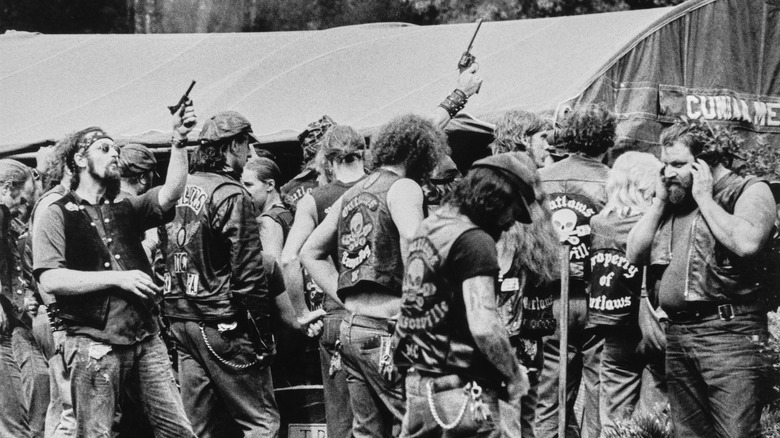

Members of the Hells Angels, Bandidos, Pagans, Outlaws, and other criminal outlaw motorcycle gangs are colloquially known as one-percenters. Initially used to illustrate how the vast majority of motorcyclists are law-abiding, this term is now worn like a badge of honor by the big four outlaw motorcycle gangs. Emerging from a controversial Life magazine article documenting debauched riots at the 1947 American Motorcyclist Association races in Hollister, California, the distinction underpins a difficulty for both riders and law enforcement: while the differences between outlaw motorcycle gangs and motorcycle clubs are distinct, not all members of outlaw gangs are involved in criminal activities. Often, determining members' criminality is difficult — even for the members.

With this in mind, many wonder whether membership alone is enough to throw them into the same legal bucket as one-percenters. To find out, we turned to lawyer and retired FBI agent Bobby Chacon, whose 27-year career included becoming an expert on the Jamaican Posse gangs, establishing the bureau's underwater forensic program, and counterterrorism postings in Baghdad and Athens.

Is membership illegal?

The answer to whether membership alone is prosecutable is both straightforward and complex. At its most basic level, Chacon tells SlashGear that no, members of legally designated outlaw motorcycle gangs cannot be prosecuted for membership alone. As he puts it, "Everyone arrested has to be individually charged with a crime."

So why is membership in an outlaw gang not considered a crime? Well, the right to assembly is protected by the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution. So as a general rule, enforcement agencies cannot prevent people from joining without proof that they're engaged in illegal activity. This became a point of conflict when Los Angeles made injunctions a key cog of its anti-gang strategy in the 1980s. Since then, the proliferation of gang databases and "predictive policing" that seeks to forecast who will commit crimes has brought the question of guilt by association to the forefront of the American justice landscape.

However, Chacon posits that criminal charges must be filed against an individual for specific criminal actions — not mere association. This extends to common tools in addressing gang-related violence, like conspiracy and racketeering cases. Even in these instances, he says, "each member of the conspiracy is charged separately and individually for their role in the conspiracy. Every arrest has to be tied to their own criminal behavior."

Simply put, to be prosecuted, you need to be involved in criminal activity. But does that mean that members of outlaw motorcycle gangs are in the clear?

RICO cases highlight the risks of criminal association

The danger for members of these gangs isn't that they are guilty by association, but rather that their membership might enlist them in criminal conspiracies regardless of their intentions. One common instance is in Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act cases, known as RICO cases, which bring the unrelated crimes of a criminal enterprise together under a broad umbrella of racketeering.

Now a matter of common parlance due to their proliferation in pop culture, RICO cases are of particular concern to motorcycle gang members — even those who don't consider themselves one-percenters. Asked if members of outlaw motorcycle gangs could be brought into a RICO case without directly participating in criminal activity, Chacon warned that while "many different activities on behalf of the 'Organization' (the "O" in RICO) are often downplayed or looked at as noncriminal," they may form the basis of charges anyway.

Using an example from his career, Chacon recounted how a 19-year-old was sentenced to 20 years in prison for delivering packages and driving family members to make bank deposits on behalf of his brother — who he knew was a drug dealer. While, on the surface, neither of these acts seemed illegal to the teen, their furtherance of a criminal enterprise subjected him to a RICO charge.

What is a RICO offense and are past members in the clear?

So what does that mean for members of an outlaw motorcycle gang who are there solely for the camaraderie, jacket, and the thrill of the open road? Well, the answer is complicated.

To be hit with a RICO charge, a defendant must exhibit a pattern of racketeering activity. The RICO statute identifies 35 such crimes, including mail and wire fraud, murder, drug dealing, gambling, and bribery. And while a seemingly law-abiding motorcycle-gang member might protest that they didn't commit these crimes, Chacon warns that members who perform two or more acts that further the criminal enterprise directly or "increase or maintain their standing in the organization" could be considered guilty. To harken back to Chacon's earlier example, tangentially furthering the racketeering activities of a criminal enterprise is enough to land you in a RICO case.

For those hoping that the statute of limitations might save them from prosecution, Chacon warns that it might not be that simple. "The RICO reachback can be quite lengthy," he said, stating that even if a person can't be charged directly with a crime, "the evidence of that crime can be admissible to show the person was part of the RICO." In essence, even if a crime is outside the statute of limitations, it can still be used to establish a pattern of crime.

Recent cases highlight the dangers of outlaw motorcycle gangs

RICO cases are law enforcement's best friend when targeting outlaw motorcycle gangs, as they enable prosecutors to do away with piecemeal measures and address the entirety of the criminal enterprise. Just last month, a federal grand jury in the Southern District of Texas charged 14 members of the Bandidos with "roles in a criminal enterprise engaged in murder, robbery, arson, narcotics distribution, and witness intimidation in and around Houston."

The Justice Department's crackdown on the Bandidos, which included charges against "Survivor" star Brandon K. Hantz, is just one of a string of high-profile cases regarding outlaw motorcycle gangs in recent years, with charges brought against the likes of the Hells Angels, Red Devils, Thug Riders, and Mongols in the past year alone.

With increased levels of prosecutorial attention, it is understandable why some bikers may be concerned about the ramifications of their outlaw-motorcycle-gang membership. While membership alone won't expose bikers to prosecution, the roles and actions undertaken while a member may make riders culpable in their gang's criminal activities, drawing a delicate line between membership in an outlaw motorcycle gang and aiding in its conspiracies.

Whether that line has been crossed, Chacon notes, might be a question more suited for an experienced defense attorney. In any case, it seems that riders thinking of joining an outlaw motorcycle gang might be wise to remember the self-help axiom, "Show me your friends, and I'll show you your future."