Why Is Mars Red? Scientists Have A New Theory

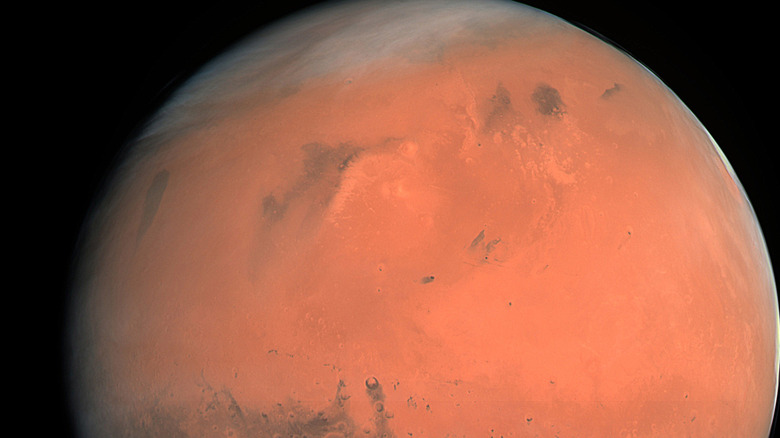

Mars is known as the Red Planet, but scientists are still learning about what gives the planet its distinctive color. New research shows why the planet's surface has its rusty hue, and the findings could even help scientists understand whether Mars could ever have hosted life.

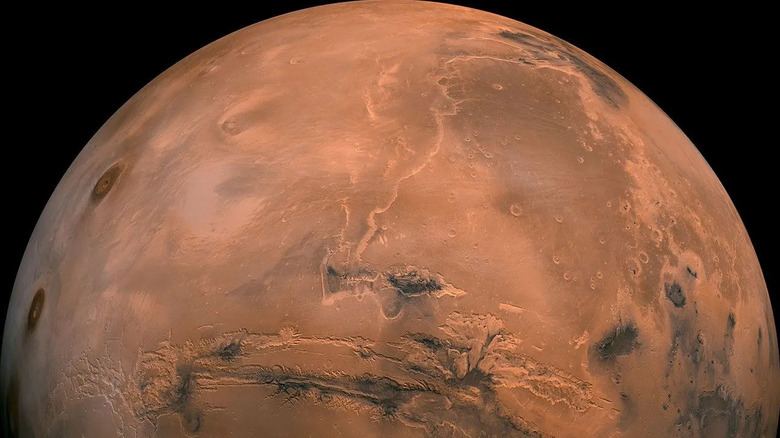

The research, published in the journal Nature Communications, looks into the material that covers Mars's surface, called regolith. This contains iron minerals, including iron oxide, which you might know better as rust. These minerals give the regolith its color. But the exact type of iron oxide that covers the planet is up for debate. Researchers used to think it was a type called hematite, which forms without any water. New evidence, though, suggests that isn't the case. In fact, the iron oxide is a type called ferrihydrite, formed when Mars was wet.

"We were trying to create a replica Martian dust in the laboratory using different types of iron oxide," lead author Adomas Valantinas, a postdoctoral fellow at Brown University, said in a European Space Agency news release. "We found that ferrihydrite mixed with basalt, a volcanic rock, best fits the minerals seen by spacecraft at Mars."

"Mars is still the Red Planet," Valantinas added. "It's just that our understanding of why Mars is red has been transformed. The major implication is that because ferrihydrite could only have formed when water was still present on the surface, Mars rusted earlier than we previously thought. Moreover, the ferrihydrite remains stable under present-day conditions on Mars."

Why this matters for explaining habitability

Researchers used data from orbiting Mars spacecraft like NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter and the European Space Agency's Mars Express and ExoMars, as well as from rovers on the surface including NASA's Pathfinder, Curiosity, and Opportunity. Together, they supported ferrihydrite being present.

One of the biggest questions for Mars researchers is whether the planet could ever have supported life. Although there's almost certainly nothing alive there now — the planet is inhospitable and dry – Mars could once have been more habitable than we thought. But although there's strong evidence that Mars could once have had water on its surface, researchers disagree about how long it was there. Water would need to have been present for an extremely long time — perhaps millions or even billions of years — for life to have developed.

So finding that the surface has ferrihydrite rather than hematite is important, because it can give a clue to how long water was on the surface — and supports the idea that Mars was wet for a long time, potentially long enough for life to have thrived.

"These new findings point to a potentially habitable past for Mars and highlight the value of coordinated research between NASA and its international partners when exploring fundamental questions about our solar system and the future of space exploration," co-author Geronimo Villanueva, associate director of the Solar System Exploration Division at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center, said in a Jet Propulsion Laboratory news release.

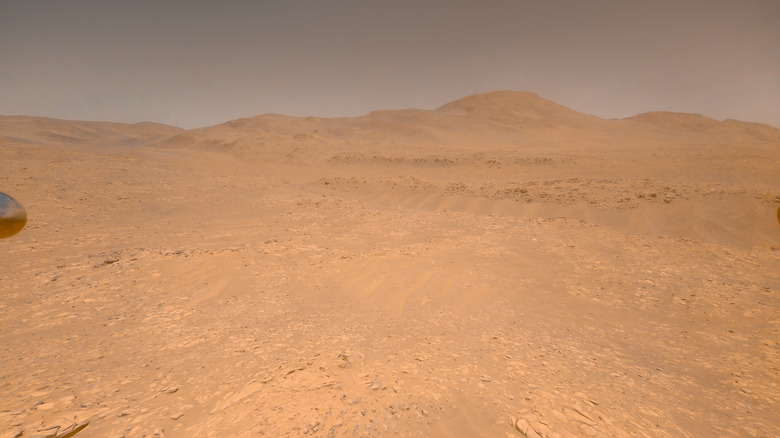

Samples from the Perseverance rover

Although this research reveals clues about how long water may have been on Mars, it's only a model of the most likely composition of regolith, given the data. To test whether the model is correct in its assumptions about Mars' past, and especially whether life could have developed there, researchers need more data. What they really want is to get their hands on a sample of Mars regolith.

That's why NASA's Perseverance rover has been collecting samples on Mars, sealing them up, and leaving them in tubes at a depot on the Martian surface. The aim is for a mission called Mars Sample Return to head to Mars, collect the samples, and bring them back to Earth for the kind of in-depth analysis that can't be done by a rover, and needs a fully equipped Earth lab.

"The study really is a door-opening opportunity," said fellow researcher Jack Mustard, a professor of earth, environmental and planetary sciences at Brown University. "It gives us a better chance to apply principles of mineral formation and conditions to tap back in time. What's even more important though is the return of the samples from Mars that are being collected right now by the Perseverance rover. When we get those back, we can actually check and see if this is right."