6 Laughably Bad Depictions Of Technology From TV And Movies

Let's face it: Representations of technology — especially computers — in TV shows and movies have never exactly been what you could call "good." As computers and the internet became increasingly mainstream and normalized, a lot of that has improved, but it's still far from perfect and has even been laughable at times. Often, it's a gross distortion of what computers are capable of, something that's especially common in crime dramas and TV shows and the world of espionage. Think about how often you've seen a cop show, for example, where a low-resolution security video needs to be improved to identify a suspect, and all it takes is using some kind of automated "enhance" button. Even in 2025, the newest AI upscaling technology isn't close to good enough to produce those kinds of results.

Other examples run the gamut. Some may be technically accurate representations of an obscure real-world computer system, but one that's so unlikely to be used in real life that its usage in a TV show or movie is questionable. Emerging technologies often get treated as a lot more mysterious and powerful than they actually are. Rapid typing is, for some reason, often shown to be the most important thing that can be done to either hack a system or try to stop it from being hacked. Some concepts are grossly oversimplified, and some entire movies are just incredibly farfetched. Let's take a look at a half-dozen of the most memorably goofy examples.

The enhance button

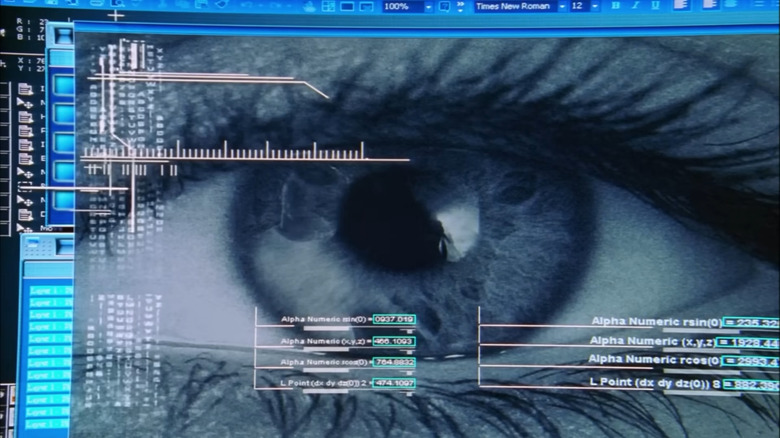

If you've watched enough police dramas and spy shows, there's one example of unrealistic tech that you've seen far too many times to count: The enhance button. The idea that forensic technicians can quickly and easily take a frame from any security video, camera phone video, etc., and, no matter the source image's resolution of the source image, "enhance" it to a very identifiable image that can be matched to a potential suspect. It's such a common, distressingly unrealistic plot device that it has its own entry on the TV Tropes Wiki. Of course, if you're reading a site like SlashGear, you probably know that even in 2025, upscaling tools are nowhere near that good.

The examples used in fiction are sometimes excessive, even by the expected standards of "enhance" as a genre convention. When searching YouTube for "CSI enhance" without quotes, for example, the first result is for a clip from an early episode of "CSI Miami" where not only are the technicians able to zoom and enhance with no artifacts but even use the enhance button to get important evidence in the reflection in someone's sunglasses in a low-resolution image. Another clip, titled "Why I Don't Watch CSI," has very similar problems, with the techs using "100x magnification" to be able to discern what was reflected in someone's eye. As the TVTropes page notes, though, this trope's occasionally subverted, like Robin Williams' character challenging an "enhanced" image in court on "Law and Order: SVU."

Hacking is typing

If you've watched enough TV shows featuring "hackers," whether the evil type or the white hat kind like Penelope Garcia on "Criminal Minds" or Detective Jet Slootmaekers on "Law and Order: Organized Crime," then you've probably noticed something that most of the hacking has in common. That would be lots and lots of typing by the "hackers." This trope is so entrenched that there's a website — HackerTyper.net — that lets you slam the keys on your keyboard to your heart's content while filling the screen of an old-school command line-esque interface with text that seemingly depicts your "hacking."

A major reason why this is so common on TV and in movies is that it at least gives the illusion of something happening on camera. "It is a requirement of any and all articles discussing hacking portrayals to bring up the scene from NCIS," explains an essay on the website of security consultants Core Security. "You know the one we're talking about. The one where the hack is not only happening in real time, it's occurring SO fast that one set of hands on the keyboard simply will not suffice, so another member of the team hops on and smashes keys as well, because we all know it's not what you type, it's how fast you type it."

Yes, as a consequence of needing to make the scene more visually interesting, these hacks are often portrayed as the real-time work of an individual hacker typing away themselves. Somehow.

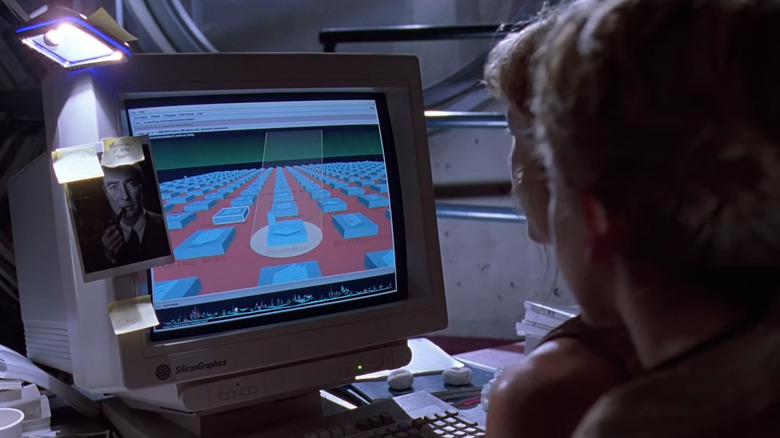

It's a Unix system. I know this.

One of the biggest movies of all time has a scene that has long come under fire for its ridiculous portrayal of computers, but there's a big twist to it. 1993's "Jurassic Park" was a technical marvel, with the computer-generated dinosaurs filling out the titular theme park looking startlingly realistic, plus the first-ever DTS-encoded soundtrack. Maybe this caused it to receive some extra nitpicking, which has often come by way of ridiculing the scene where Lex, a young hacker, has to turn the park's security system back on.

Upon finding the relevant computer terminal, she exclaims, "It's a Unix system. I know this." Lex navigates her way through an unfamiliar, fake-looking file browser with primitive 3D graphics. The ridicule is often born out of the idea that it looks much more like a filmmaker's idea of a file browser than anything actually used in a genuine Unix system.

Or is it?

Despite long being used as an example to the point that the Reddit forum for bad on-screen portrayals of computers is named /r/itsaunixsystem, the movie portrays a real Unix system (the Silicon Graphics IRIX) running an actual contemporaneously available file browser demo named fsn. Seemingly, it's an easter egg because Silicon Graphics did the movie's CGI work. Everyone assumed it was fake because it seemed too slow, impractical, and stereotypically filmic to be real software. It's slow and impractical and incredibly unlikely to be used in real life, but it's not fake.

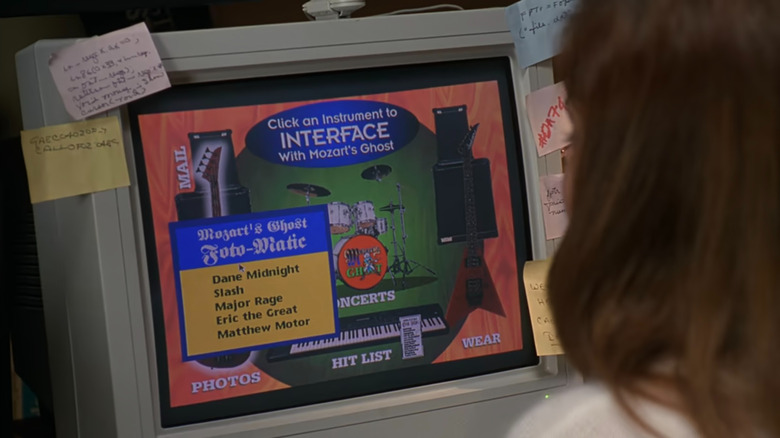

The entirety of 1995's The Net

As home computer ownership and internet usage raced further and further towards mass adoption in the mid-1990s, the potential pitfalls of the internet naturally became a popular subject in TV shows and movies. Perhaps the signature work of this moment in time is 1995's "The Net," which starred Sandra Bullock as IT worker Angela Bennett. A big part of what makes "The Net" so fascinating 30 years later is that while its portrayal of mid-'90s technology is ridiculous, its thematic elements ring a lot more true. Though they weren't necessarily accurate yet in 1995, "The Net" raises legitimate concerns about the ramifications of the world increasingly moving into the digital realm and how that could spiral out of control via identity theft, fraud, and stalking, but the nuts and bolts of it are completely ridiculous.

The movie wastes no time exaggerating what the web was capable of at the time, with websites that are rich in multimedia elements and a local pizzeria taking online orders at a time when most people were afraid to shop online and secure credit card processing would've been too expensive for a small business. Viruses work in ways that don't resemble real life at all and have wacky visual effects, alerting you to their effects instead of working stealthily as they should. And that just scratches the surface. As much as "The Net" still works thematically, it has never been a particularly accurate portrayal of computers and the Internet.

Streaming video is magic

If you find yourself watching reruns of "Law and Order: Special Victims Unit" with any regularity in syndication, like on USA Network, one episode that seems to be in fairly heavy rotation is "Spectacle," the 16h episode of season 12, which premiered in 2011. The short version of the plot is that the episode opens with shocked college students discovering a live stream of a woman being kidnapped and tortured, and the live stream turns out to be staged by one of the students. Why? Because his little brother has been missing for years, the case has gone cold, and he's desperately trying to get the police's attention.

The way that the live stream manifests, though, is where the episode gets more than a little goofy, technologically speaking. As described at the start of the episode, "I just logged on, and there it was!" Greg, the character who says this, turns out to be the one behind the stream, but lest you think he staged it showing up on his computer, the show quickly cuts to another dorm room where the video is playing. When the police speak to campus security, they're told that the stream was somehow only broadcast internally at the school. Normally, this kind of "murder.com" plot involves a secret link going semi-viral, but not here. On "SVU," the stream just kind of showed up on everyone's computers unprompted, but the episode never explains it beyond Greg's "I just logged on" comment.

One encryption key to rule them all

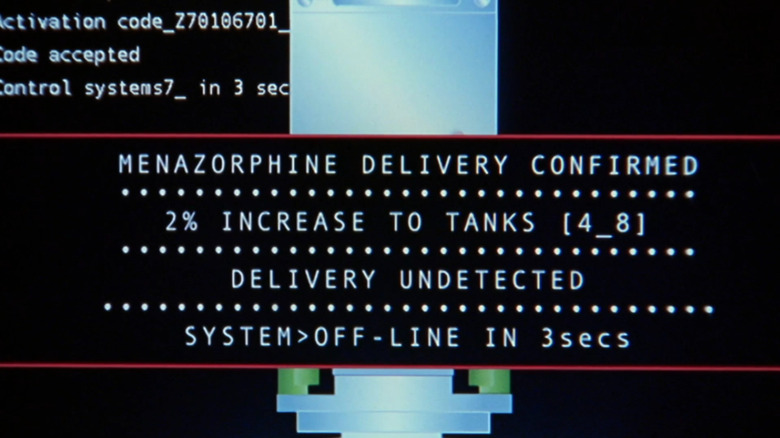

Law enforcement-themed TV shows tend to play pretty fast and loose with accurate depictions of technology, so it's only natural that their spiritual cousins in the form of spy shows often do the same. "Alias" and "24" are probably the most famous offenders, but one example that stands out in particular comes from a British contemporary of theirs, the BBC's "Spooks." (The show was renamed "MI-5" in the U.S. due to concerns most viewers would be more likely to think of "spook" more as an anti-Black racial slur.) In the show's third season, the seventh episode, "Outsiders," is egregious for relying on the premise that all internet encryption could be undone if bad actors simply acquired the right key.

Exactly what the central plot is takes a bit of time to uncover: First, poison is inserted into over-the-counter pain relievers at the automated assembly line level. Then traffic lights start going haywire, and calls to 999 (England's version of 911) are redirected to phone sex hotlines. At this point, Andrew Forrestal, a computer security expert on loan from sister agency GCHQ, realizes what the acts of sabotage have in common: All of the breached systems relied on "the G&J Algorithm," described as "the basis of virtually all internet electronic encryption," which can be hacked with a common key. Obviously, nothing like this exists in real life, and for good reason. Understandably, real-world encryption standards, like AES, aren't broken via a universal key.