Nose Art: A Brief History Of The Personalized Painted Planes Of WW2

Combat is chaotic. Identifying friend from foe was critical in historical hand-to-hand fighting and continues to be so in the modern age. From the earliest standing militaries in the Middle East's ancient Fertile Crescent region — often called the cradle of civilization by historians — armies have used insignia and images to denote everything from rank to reward. Ancient charioteers adorned their vehicles. The tribunes of ancient Rome wore purple stripes on white cloaks to denote rank. The golden eagle standard of a legion was the soul of a command. It was a mere symbol, yet its loss was considered the worst kind of defeat.

Soldiers led difficult lives of privation and pain. The images and insignias a unit carried into battle came soaked with the blood and sweat of the fallen. As modern warfare bloomed in the wake of the Renaissance, ranged warfare became more common. The 20th century was the most violent in human history. Two world wars sent at least 60 million people to their deaths due in part to technology made possible by the Industrial Revolution. Long gone were the days of swordsmen and archers. Developing an esprit de corps and identity in the face of such violence became the prerogative for many fighting men and women.

Humans now fought on land, under sea, and in the air. The First World War saw the advent of aerial combat, which brought a curious new addition to the history of art in warfare — images began appearing on the aircraft. These illustrations served as everything from unique identifiers to marks of ferocity to laments about the people left behind. We dive into the history of nose art to find out how this curious artistic element made its way into the 20th century.

Aircraft art became an expression of the pilot during World War I.

World War I broke out 11 years after the inaugural flight of the Wright Flyer in 1903. Like most new technologies, humanity soon set about fitting the aircraft to a role in warfare. When hostilities erupted, international powers began to use aircraft in combat for the first time. Identification was one of the early challenges faced by this new form of combat. At an appropriate distance, every airplane looks like a speck on the horizon, and identifying one as friendly — or not — could be the difference between life and death.

Early World War I aircraft were primarily used for reconnaissance. Still, as technology and the death toll advanced, pilots soon found themselves armed to the teeth and engaging in swirling high-altitude mortal combat in fragile and sometimes unreliable machines. Picking an enemy out from your allies was critical to the dogfighting process, as no one wanted to be misidentified and downed by their own side. As ground troops had been doing for millennia, flying units began using standardized insignia.

For pilots, their fighters were more than just machines – they were extensions of themselves and partners in battle. Many pilots began to personify their planes. Others built a reputation for success bolstered by the unique design scheme on their aircraft.

The practice spreads

Legendary fighter pilot Manfred von Richthofen — famously known as the Red Baron – was a German fighter ace who significantly contributed to the evolution of aircraft aesthetic customization. His bright red Fokker triplane, adorned with the Iron Cross of Germany, became a legend. His unit, Jasta 11, earned the nickname Flying Circus due to its fleet of garishly colored aircraft. Allied pilots returning to their aerodromes with tales of brightly painted German aircraft added to his mystique. The trend of personalizing an aircraft spread on both sides of the conflict.

While German pilots primarily painted their entire aircraft, the French popularized the idea of a personal name or insignia. The practice spread amongst pilots on both sides. Take, for instance, the Italian Count Francesco Baracca and his prancing horse insignia, which later inspired Enzo Ferrari when he chose his company's logo. When the United States joined the war, American pilots introduced new themes — American symbology in the form of eagles, Uncle Sam, obstinate mules, and others. Some units shared an insignia or illustration to boost camaraderie or supply identity to a disparate group of people who needed to operate as one under intense conditions.

In a display of defiance, many individual pilots used nose art to challenge the system. They often altered their aircraft without permission from the command, effectively thumbing their nose (art) at the military hierarchy. Nose art became an expression of self in a war machine that didn't respect the individual.

The golden age of nose art

The interwar years saw vast improvements in aviation. Aircraft became more powerful and capable of more extended range, higher speeds, and increased armaments. Monoplanes replaced the bi- and tri-planes of World War I. Enclosed cockpits and radio communication revolutionized tactics. It was an exciting time for aviation, but an unlikely new industry grew alongside it, and soon the two would merge unexpectedly.

Cartoons had long been a form of expression when animated movies like Walt Disney's Steamboat Willie began to captivate audiences. In 1930, the antics of the Looney Tunes gang delighted and entertained future combatants. "Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs" debuted in 1937. The power and popularity of illustration grew along with the burgeoning new form of entertainment. In a world where black-and-white photography was the norm, stunningly colored illustrations had a powerful impact.

When World War II broke out in September 1939, it swiftly became a total war. The practice of using nose art to build camaraderie and esprit de corps roared back into vogue as aerial combat took on a new ferocity. As young men flocked to undertake pilot training, they brought a mixed bag of motivations, priorities, and experiences. Some were driven by a sense of duty, others by a desire for adventure, still more by a need to prove themselves. They would soon meet in the skies over the world's battlefields, many wearing their hearts painted on the noses of their machines.

The Flying Tigers and the shark's grin

The use of nose art varied by nation and unit. Some, like the United States Navy, strictly forbade its pilots from customizing their aircraft in the name of military discipline. Meanwhile, the United States Army Air Forces encouraged it. The Royal Air Force of the United Kingdom reluctantly allowed it when foreign squadrons began joining the fight after the Battle of Britain.

The Flying Tigers were a unit of fighter pilots that belonged to no nation, composed of American volunteers who flew P-40 Warhawks in the Pacific Theater before the United States entered the war. The Tiger pilots combated the Japanese in the skies over China. Unbeholden to typical military regulation, the Tigers painted their aircraft with one of the most famous examples of nose art: the shark grin.

The Tigers were not the originators of the predatory fascia, which had sharp teeth and eyes fixed on some distant target. German pilots used similar themes during World War I, but the Tigers brought this striking example of nose art to the forefront early in the Second World War. As the war grew in scope, other pilots followed the example, reviving the practice their fathers had started decades earlier.

Aggression is a favored trait among combat pilots, so it made sense that an image expressing that, like the shark grin, appeared on aircraft. But another thought filled the minds of young men far from home and facing death: women.

The pinup and the people at home.

Pinup illustrations of buxom women exploded in popularity during the war years. Commercial artist George Petty popularized the concept of the pinup with his work for Esquire magazine. Peruvian artist Alberto Vargas took up the mantle when Petty left to focus on advertising. Images of models Hedy Lamarr, Rita Hayworth, and Betty Grable made the women wartime icons.

Many American women served as Woman Airforce Service Pilots, known as WASPs, and in combat roles in the U.S.S.R., but the vast majority of combat pilots were men. Generally ranging in age from 18 to 40, they came from many walks of life. Some were married with children, and the war interrupted their domestic lives. Others were fresh out of school, inexperienced and wrenched into war without the chance to experience romance. Whatever their background, many took to their planes to express their feelings toward fairer sex.

Many pilots identified with the curving grace of their aircraft, gifting the plane with a feminine identity all its own, often referring to the aircraft as "she." It was the aircrew member and his plane against the world. She would bring him home safely, or they would die together. It didn't take long for pinup art to begin appearing on planes. While many centered around the youthful urges of the young men manning the airplanes, some focused on love rather than lust. Pilots often named their aircraft after the women they left behind, painting their images on the fuselage in homage to those they loved.

Pop culture and patriotism

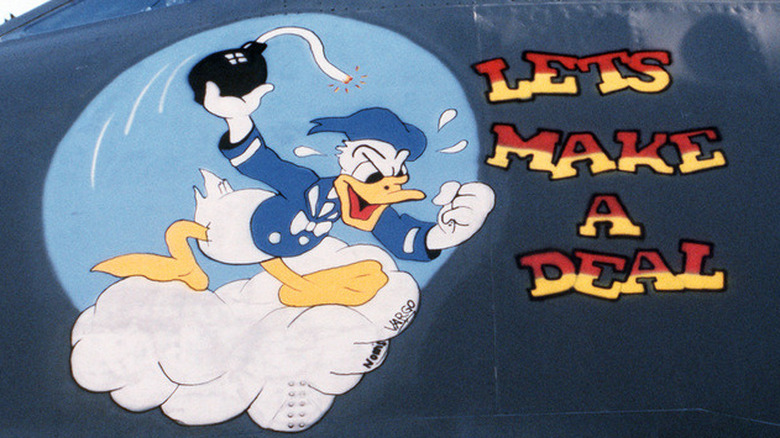

It wasn't just amateur artists getting in on the nose art action. Surprisingly, major studios in the United States also took part. Artists working for Walt Disney created over a thousand illustrations that were used as nose art and other military insignia, which meant that Donald Duck and the rest of the gang doffed military uniforms to fight alongside the men and women who grew up with them.

The proliferation of nose art, sometimes humorous, sometimes vulgar, and sometimes aggressive, was a clear sign of the burgeoning power of American popular culture. The fact that organizations like Disney and Warner Brothers pitched their resources into the war effort speaks volumes about the all-encompassing impact of World War II on American life.

It's not just about the art but the personal stories behind it that make nose art so compelling. The country song "Pistol Packin Mama" about an angry wife confronting a lecherous husband inspired the crew of a Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress to name their aircraft after it, complete with appropriate nose art. Sadly, that aircraft and crew were lost over Germany in 1944.

Nose art was more than just a decorative touch. It was a rare splash of personality in the military world of uniformity, a touch of color in a dark and dour period. It also served as a mirror into the souls of the airmen who took to the skies, risking life and limb to drive back the totalitarian menace.

The legacy endures

World War II proved to be the high water mark of the nose art trend. Peacetime military regulations are often more strict, and not everyone was keen on carrying the idea into the future. During the Korean War, the practice flared up again. Though most common on Air Force planes, the Navy and Marines increasingly used nose art through the Vietnam era.

Though nose art endured for a few decades, in the latter half of the 20th century, military units increasingly transitioned from personalized paintings on aircraft to a more standardized approach. Some units still keep the tradition alive, but they are the exception rather than the rule. The 74th, 75th, and 76th Fighter Squadrons of the United States Air Force, which trace a lineage to the Flying Tigers, use the shark grin on their A-10 Warthogs.

Like the age of the aerial dogfight, nose art has become something of an anachronism, representing a time when wars were fought differently. Thanks to organizations like the Commemorative Air Force, the memory of nose art is being preserved, along with the surviving warbirds and thousands of photographs of the era that have filtered down through time.

From humble beginnings as common-sense identification aids to the personal expression of pilots and aircrew, nose art remains a curious example of how art and warfare combined in the fight against totalitarianism.