Danyang-Kunshan Grand Bridge: The History Behind The Longest Bridge In The World

China's booming economic growth and the associated explosive growth of its cities have led to infrastructure projects that have rewritten the record books. Half of the world's longest bridges are found in the People's Republic of China. This amazing growth in road and railroad bridges exists to serve the huge numbers of people moving to Chinese cities, along with a thriving industry building electric vehicles and other automobiles. China also operates some of the fastest high-speed trains in the world. These dynamic transportation networks drive the construction of some awe-inspiring bridges.

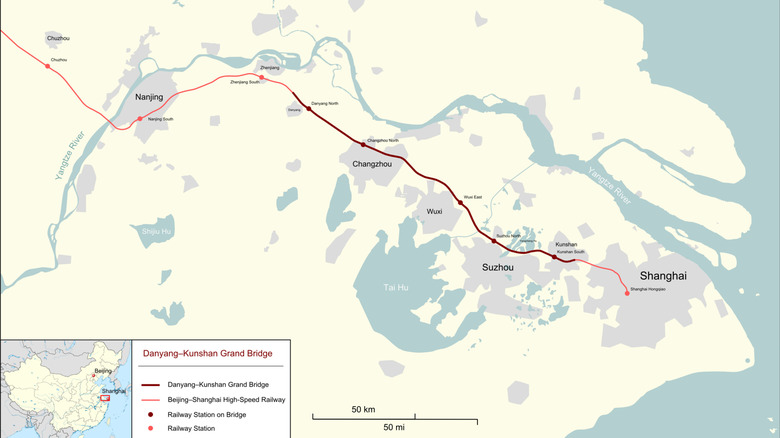

The longest of these, and the longest bridge in the world, is the Danyang-Kunshan Grand Bridge. This structure, a cable-stayed bridge and railway viaduct, runs for 102.4 miles and connects the thriving cities of Shanghai and Nanjing. It carries a stretch of the Beijing-Shanghai High-Speed Railway along tracks parallel to the Yangtze River. Danyang is a suburb east of Nanjing, and Kunshan is west of Shanghai. The bridge shortened a four-and-a-half-hour trip between the cities to just two hours.

It also demonstrated 21st-century China's expertise in massive infrastructure projects. With most of its length being an elevated viaduct, the bridge solved an essential transportation problem while minimizing its footprint on the surrounding landscape. Its engineers also designed it to withstand natural and man-made catastrophes. The bridge also represents China's expertise in operating high-speed rail, including its groundbreaking Fuxing Hao trains, a maglev bullet train, and the world's longest high-speed rail line between Beijing and Guangzhou.

The history of viaducts

Most of the bridge's length consists of an elevated railway viaduct. Viaducts have a long history in railway engineering. The 1,000-foot Glenfinnan Viaduct in Scotland, famous for carrying the Hogwarts Express in the "Harry Potter" films, was built in the 1890s. A viaduct is a series of bridge segments that carry a roadway or railroad above a low-lying region, as opposed to bridges built over water, a canyon, a deep valley, or a road. Viaducts can cross water or valleys if these obstacles lie along the viaduct's route. Segments can also run through tunnels or merge with other bridges for brief stretches.

The Danyang-Kunshan Grand Bridge is far longer than the Glenfinnan Viaduct, and at first glance, it might seem like an expensive and difficult way to build a railway. However, viaducts offer numerous advantages over traditional railroad beds. They make efficient use of land, enabling everything from farms to factories to exist in close proximity to the railroad right-of-way. In the case of the Danyang-Kunshan Grand Bridge, using a viaduct-style railway reduced the acreage required by almost two-thirds compared to a ground-level railroad bed.

This is especially important in the crowded landscape of eastern China. Beijing and Shanghai, the cities at either end of the high-speed rail line of which the bridge is a part, are two of the world's largest cities. The corridor between them supports a vast population. While it's primarily low-lying land, it's not entirely flat. High-speed rail ideally requires straight and level tracks, and building a viaduct allows engineers to pass right over minor elevation changes and other obstacles in the landscape. It also eliminates road crossings while enabling the use of prefabricated bridge segments.

Why China needs the longest bridge in the world

Jiangsu Province, where the bridge is located, is both a historical heartland of China and a center of modern, high-tech growth. Bordering Jiangsu to the south and also next to Kunshan sits Shanghai, one of the major seaports and commercial centers of the world. Its population has exploded from about 6 million in 1980 to almost 30 million in 2024. 102 miles away, near the Danyang end of the bridge, the city of Nanjing has quintupled in population over roughly the same period.

Within that corridor, Danyang and Kunshan themselves also grew in population and importance. Danyang sports a population of almost 1 million, making it much more than just a suburb. It is home to industries ranging from car parts to textiles but is most renowned as one of the world's leading manufacturing centers for eyeglass frames and lenses. Kunshan isn't far behind Danyang in population, with over 860,000 residents, and is known for its scenery and a nearby historical site called Zhouzhuang Water Town.

Given the growth in population, commerce, and tourism in recent decades, there was an obvious need for a transportation option that would cut the travel time across this 100-mile zone. With the area's heavy population, existing roads, and agricultural land, a railway viaduct made the most sense to connect these metropolises.

The China Communications Construction Company Limited built it

The principal company behind building the bridge was the China Road and Bridge Corporation (CRBC). CRBC is one of four major state-owned Chinese companies that specialize in infrastructure projects like roads, bridges, ports, and railways, both within China and internationally. It is a subsidiary of a Fortune 500 company called China Communications Construction Company Limited (CCCC). The company operates in over 120 countries across multiple continents and extends CCCC's reach overseas as part of China's Belt and Road Initiative. As part of China's foreign outreach, CRBC has completed several international projects.

With the region growing exponentially, it was time to build a new high-speed rail connection, and for the trains to pass through the crowded landscape, a viaduct was needed. CRBC was chosen to build the new structure. With a workforce of 10,000 and a four-year timeframe for completion, construction began in 2006. By the time it was complete, it would rank as the longest bridge in the world, according to the Guinness Book of World Records.

How engineers constructed the bridge

Most of the bridge consists of prestressed concrete beam construction. Concrete pillars support each bridge deck, and each deck is constructed as a box girder. In this form of construction, hollow girders run along the length of the bridge from one set of support pillars to the next. The girders support the deck, along which runs a roadway or railway (or both). The girders can be cast of prestressed concrete, structural steel, or a composite of both. This method of building a viaduct offers several advantages. Its hollow shape keeps weight down while still offering high strength and torsional resistance, both of which are important for building longer spans that are subject to high stresses.

Box girder bridges can be built in a modular, prefabricated manner for high-speed construction. Girders are cast on-site in specially built plants to minimize the expense of transporting segments. Each span can then be lifted into place with cranes or gantries. In the case of the Danyang-Kunshan Grand Bridge, because of its tremendous length, four prefabricating plants were built along the length of the project. Most spans were 32 meters long or about 105 feet except for longer sections where needed to cross over various obstacles. The bridge runs at an average height of about 100 feet above the ground.

A 5.6-mile section of the bridge crosses Yangcheng Lake west of Shanghai. Here, the bridge rests on 2,000 pillars and is supported by steel cables. Combined with 9,500 pillars on the overland portion of the bridge, that adds up to 11,500 pillars supporting the bridge as a whole. It required hundreds of thousands of tons of steel and cost $8.5 billion to complete. Construction was completed in 2010, and the bridge opened in 2011.

How the Danyang-Kunshan Grand Bridge is disaster-proofed

Any bridge must be strong enough to withstand whatever disasters might befall it, but this is doubly true for high-speed rail bridges. With trains traveling at speeds exceeding 200 mph, there is very little time to react if a bridge segment collapses or even gets shaken slightly out of alignment. The engineers of the Danyang-Kunshan Grand Bridge deployed several technologies to boost the bridge's safety. For instance, the portion spanning Yangcheng Lake has over 16% of the bridge's total number of pillars, even though it makes up only about 5% of its total length. This helps the bridge to withstand strikes from vessels weighing up to 300,000 tons.

It's also designed to withstand an earthquake of magnitude 8. Expansion joints allow the track sections to move without damage if the ground shakes. The bridge also features base isolators, which are like shock absorbers that allow the ground to move without transferring the movement to the structure above the isolators. An elastomeric bearing is one type of base isolator used by the engineers. These bearings consist of thick layers of rubber between steel plates; the steel plates are attached to the upper and lower portions of the structure, while the rubber layers transfer vertical motion into horizontal movement. The bridge also uses sliding plates to absorb horizontal movement of the ground.

Given eastern China's vulnerability to typhoons blowing in from the Pacific Ocean, wind resistance is critical, too. The bridge's anchorage has been aerodynamically designed to withstand very high winds. It also uses stainless steel and high-tech coatings to guard against corrosion that could weaken the structure. This will help to meet the goal of a 100-year lifespan for the bridge.

Traveling the Danyang-Kunshan Grand Bridge is scenic

Thanks to the bridge's advanced construction, trains can travel smoothly up to 217 mph along the Beijing-Shanghai High-Speed Railway. Combined with the viaduct's average height of 100 feet, that gives travelers an extraordinary view of the landscape as it glides serenely by outside the train's windows. In addition to urban landscapes, the railway passes through countryside rich with rice paddies, along with rivers, lakes, and plains, all saturated with thousands of years of history.

Just west of Shanghai, the railway passes through Suzhou, a metropolitan area based around a city founded in 514 B.C. Suzhou has often been called the Venice of the East, thanks to its canals, culture, and history. Tourists come from around the world to see its pagodas, bridges, and gardens. A favorite destination of travelers is Zhouzhuang Water Town, which is crisscrossed with canals lined with ancient houses. Suzhou's classical gardens are considered a masterpiece. While you won't see these attractions from the train, the surrounding landscape offers stunning vistas unfolding as the train soars past them.

Four stations are integrated into the bridge so travelers can disembark at Kunshan, Suzhou, Changzhou, and Danyang. This makes the railway an excellent way to experience the culture and history of the cities along its route. And, of course, Shanghai is nearby with its incredible skyline of stunningly modern skyscrapers stretching as far as the eye can see. At the other end of the bridge, Nanjing offers museums, temples, and other attractions for tourists.

The bridge inspires flat-earther conspiracies

Impressive accomplishments sometimes attract strange ideas from people who doubt their veracity. Consider the skeptics who think aliens built the pyramids or advance the moon landing conspiracy. In the case of the Danyang-Kunshan Grand Bridge, the conspiracy theorists have taken a different tack: Some folks have decided that the bridge proves the earth is flat.

Bear with us momentarily since their reasoning may be hard to follow. Flat-earth enthusiasts say that since the bridge is perfectly level with no curvature, the earth underneath it must be flat. According to them, if the world were round, the bridge would rest on top of it at only one point, like a ruler sitting on top of a basketball. Since the bridge stays the same distance from the earth from one end to another, the earth underneath it must be flat, too.

Fortunately, this is easy enough to debunk. First, the bridge is built in hundreds of segments, and the earth's curvature is negligible between one segment and the next. Secondly, when bridges have exceptionally long spans, the earth's curvature actually affects how they are built. Consider the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge between the New York City boroughs of Staten Island and Brooklyn. Its central span is so long that the earth's curvature affects its construction. The bridge's towers are perfectly perpendicular to the earth's surface, and since the planet curves between them, the tops of the towers are over an inch and a half further apart than their bases. It stands to reason that if we could measure the towers at each end of the Danyang-Kunshan Grand Bridge, we would see an even bigger deviation.