These Hulking Electric Trucks Will Soon Worsen What They Were Destined To Fix

There has been a clear trend observable in the global EV market for the past few years. If it's big, it sells. That approach, however, is defeating the fundamental purpose of electric cars. EVs marked their arrival with a massive hype around their environmental appeal, and how they were reducing the pollution burden as well as ownership costs compared to combustion engine rides. According to a fresh analysis published in the PLOS Sustainability and Transformation journal, EVs with bigger batteries are not reducing greenhouse gas emissions against fossil-fuel-based cars in the expected fashion.

Moreover, they end up requiring 75% more critical minerals, and the carbon dioxide emissions tied to their assembly from scratch are also 70% higher. In a nutshell, the ever-increasing size of electric vehicles is putting the supposed environmental gains in the reverse gear. "The true energy consumption and lifecycle greenhouse gas emissions are hidden from consumers," Perry Gottesfeld, author of the paper, told SlashGear.

"The current US EPA MPGe that is consumer-facing on all new vehicle stickers only accounts for electricity consumption during the use stage but ignores the energy needed to mine, refine and manufacture the lithium-ion battery," says Gottesfeld, currently serving as the Executive Director of Occupational Health at Knowledge International. The underlying problem here is the customer preference for SUVs and other large-format electric cars, which come equipped with hulking battery packs. As per an analysis by the International Energy Agency, of the nearly 600 models of electric cars available globally, two-thirds fall in the "large vehicles and SUV" class.

Big EVs, bigger problems

It's obvious that large electric vehicles would also require correspondingly huge battery packs. But the situation has started to reach absurd levels with the likes of the GMC Hummer EV, Tesla Cybertruck, Ford F-150 Lightning, and the Rivian R1 hitting the roads. Take, for example, the GMC Hummer EV. It comes equipped with a battery pack that outweighs an electric car like the Fiat 500e, a hybrid like the Toyota Prius, a speed demon such as the Koenigsegg Gemera, and is almost as heavy as the 2025 Honda Civic Si itself. And what does it offer in return for a battery pack that tips the scales at roughly three thousand pounds? According to GMC, around 367 miles for the 2025 model.

It is evident that the size of battery packs inside large electric cars does not proportionally translate to a range gain. Citing an insight published in Energy Policy, Gottesfeld points out that for every 1% gain in vehicle weight, the car's electricity consumption also goes up by the same measure. The paper also notes that charging such EVs will also lead to a substantial load increase on the national electricity grid.

The IEA estimates that if all the electric SUVs sold in 2023 had instead been medium-sized cars, we could have saved a massive 60 GWh of battery equivalent power worldwide. The Energy Policy paper also mentioned that policymakers may "have to intervene to mandate reductions in EV size." The IEA notes that there is a greater incentive to market electric SUVs as they open the doors for higher profit margins, thanks to the tax credits trimming the final sticker price for buyers.

The outsized impact of large battery packs

It's easy to see brands increasingly preferring large formats like SUVs over smaller cars in their quest for electrification. While big names such as Tesla, Ford, GMC, and BMW have served their fair share of EVs, even upstarts in the East and the Global South, such as BYD, Geely, and Mahindra, have made their preference for large electric vehicles public. But it's not just the grid stress and the lack of corresponding efficiency gains that make electric SUVs problematic — it's their emission burden.

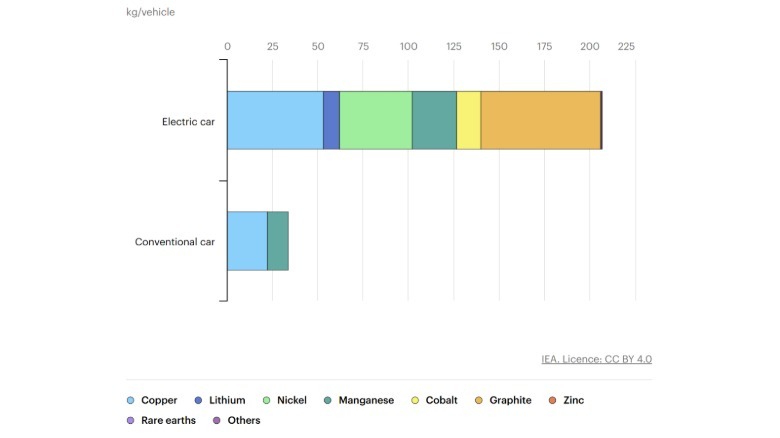

"Life-cycle GHG emissions would increase by approximately 25% largely due to the 75% increase during battery production," writes Gottesfeld, who is also a member of the California Environmental Protection Agency's Lithium-ion Car Battery Recycling Advisory Group and served on the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's Advisory Committee on Childhood Lead Poisoning Prevention in 2019. An EV requires six times more minerals (per unit weight, and also in variety) than a gas guzzler, and the mining demand to feed them copper, nickel, cobalt, and lithium is only poised to grow in the coming years. The subsequent mining operations, as a result, are leading to large-scale deforestation.

According to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), non-exhaust emissions from electric vehicles — such as tire wear, dust resuspension, and road wear — are higher than ICE rides owing to the former's heavy battery packs. "This is particularly the case for electric vehicles with greater autonomy (driving range) that require larger battery packs," says the OECD report.

How to fix the situation?

A majority of buyers are swayed by the green appeal of electric cars and how they translate to a neat cost benefit in the long run. There is, however, not enough awareness regarding the size of EVs they pick, especially in the context of their environmental footprint. It is hard to say whether that knowledge will sway their opinions. "Certainly we need to do more to inform consumers about the actual lifecycle energy consumption of EVs and the benefits of smaller lithium-ion batteries," Gottesfeld tells me.

A white paper by the American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy (ACEEE) also warns if the current market preference for large EVs continues, it will not only dilute the promise of efficiency that comes with EVs, but will also raise costs and emissions. The ACEEE also notes that the government should take a look at revising the rebate and credit structure to boost the adoption of EVs that are more efficient.

"This is another near-term opportunity for states to affect the EV market, incentivizing drivers to purchase more efficient EVs and automakers to sell them," says the non-profit, which focuses on energy and climate change policies. Gottesfeld also told me over an email correspondence that government incentives should pay attention to the net greenhouse gas (GHG) profile of an electric vehicle and the battery pack tied to its powertrain before doling out incentives for buyers as well as companies selling these cars.