10 U.S. Fighter Jets That Never Took To The Skies

On October 14, 1947, a B-29 Superfortress bomber took off with a small, dart-shaped, rocket-powered aircraft called the Bell X-1 slung under its belly, nestled partway into its bomb bay. Air Force Capt. Chuck Yeager sat in the X-1's cockpit. He had named the X-1 "Glamorous Glennis" after his wife. At 23,000 feet, the X-1 dropped from the B-29's underside and Captain Yeager climbed to 43,000 feet. He then piloted the X-1 through the sound barrier, becoming the first person to go supersonic. He also blazed the trail for dozens of experimental aircraft and their pilots to take to the skies under the X-plane program.

X-planes included propeller-driven aircraft, jets, rocket-power craft, and even some helicopters. Most were intended to win contracts to become production models, or to test new technologies or novel configurations of wings or rotors. All were dangerous to fly by definition since no one could know whether a new design would get airborne (and stay there, and land safely) until a brave test pilot took off. X-plane jets perhaps best captured the daring image of test pilots in the public's imagination, especially since so many of these pilots became NASA's first astronauts.

Yet for all of the pilots' bravery and the inventiveness of the engineers who designed the plans, not every experimental jet fighter would go on to reach production. Sometimes the aircraft had fatal flaws, failed to reach performance goals, or simply weren't as good as the experimental planes they were competing against for an Air Force or Navy contract. Many of these were fine aircraft and some would become legends in their own right, but they just didn't quite make the cut. What follows are 10 U.S. fighter jets that never took to the skies as production models.

McDonnell XF-85 Goblin

The X-85 Goblin had one of the most descriptive names of any aircraft, perfectly describing its tiny and comical proportions. With its short, thick fuselage and improbably stubby wings, it hardly looks like it should fly. There was logic for its odd form factor. The Goblin was a parasite fighter designed to be launched from a bomber. Specifically, it had to fit within the bomb bay of a B-36 Peacemaker, one of the Air Force's workhorse bombers in the early years of the Cold War.

The need for a parasite fighter was evident as early as 1945, as the longer ranges of the Air Force's newest bombers meant they could outfly the range of their fighter escorts. The X-85 Goblin was intended to provide a built-in fighter escort, ready to be deployed at the first sign of enemy fighters. A trapeze would lower the Goblin from the bomb bay and release it into the skies, ready to fight with its four .50-caliber machine guns. The Goblin weighed around 4,550 pounds, or about 5,600 pounds fully loaded. Despite its highly un-aerodynamic appearance, the little jet could reach 650 mph thanks to 3,000 pounds of thrust produced by its single Westinghouse XJ-34 turbojet engine.

The Goblin was reportedly easy to fly, too, even with its tiny wings. It was designed to complete its mission and then hook back onto the trapeze to be raised back into the bomber's belly. However, in test flights conducted in 1948, turbulence made it difficult for the Goblin pilots to catch the trapeze. Coupled with the fact aerial refueling systems were becoming viable, extending the range of conventional fighter escorts, the X-85 was canceled.

Lockheed XF-90

The XF-90 continues to enjoy a great reputation after more than seven decades despite never entering production, as the first U.S. Air Force jet prototype with afterburners and also being tough enough to survive a nuclear blast. Its design arose from the Air Force's need for a penetration fighter to travel deep into Soviet airspace while escorting bombers. It needed to be fast, have a tremendous range, and be able to hit ground targets if needed.

Kelly Johnson and his legendary Skunk Works team at Lockheed built the XF-90. To make the jet sleek enough for supersonic flight, the team gave it a long needle nose and wings that swept back at a 35-degree angle. This was an innovative design during an era when the Air Force's existing jet fighter, the F-80 Shooting Star, had the straight-out wings and stubby nose of World War II propeller-driven fighters. The XF-90 used two Westinghouse XJ-34 turbojet engines to which the Skunkworks Team added afterburners. Armaments consisted of six nose-mounted 20-millimeter cannons. The jet's flying range was an impressive 2,300 miles. It first flew in 1949.

While the XF-90 reached supersonic speeds on several test flights, it never went as fast as the Air Force had hoped, generally topping out at a barely-supersonic 665 mph. The XF-90 was heavy and lost a flying competition to the lighter McDonnell-Douglas XF-88 Voodoo prototype. The Korean War also changed the Air Force's priorities away from long-range penetrators, and the XF-90 was canceled. However, it earned legendary status in 1952 by surviving a nuclear test with little damage.

Convair XF2Y-1 Sea Dart

The Convair Sea Dart jet fighter prototype arose from twin concerns of the U.S. Navy during the late 1940s and early 1950s. First, the Navy doubted whether the new generations of high-performance supersonic fighters could operate off its existing fleet of aircraft carriers. Second, the Navy wanted to implement a "Mobile Base Concept" in which water-based fighters would give it a global reach. To address these concerns, the Navy turned to Convair to build one of the world's first supersonic seaplanes.

The remarkable XF2Y-1 Sea Dart first flew in 1953. To take off from sheltered waters, it rode a pair of hydro skis that retracted in flight. The first prototype (out of five eventually built) was powered by two Westinghouse J34-WE-32 engines which produced 3,400 pounds of thrust. Subsequent prototypes received the engine that the plane's engineers intended: a pair of J46 turbojets with afterburners and 4,600 pounds of thrust. The engines rode above the wings to keep them out of salt water. Other adaptations to its marine environment included bulkheads in a watertight fuselage to prevent the plane from sinking if it returned with battle damage.

The Sea Dart proved that the jet seaplane concept could work, but taking off from the water created turbulence that was rough on pilots. It also could only achieve supersonic speeds in a dive, and it did so only once. These factors and a tragic accident during a public demonstration of the plane led to its cancellation.

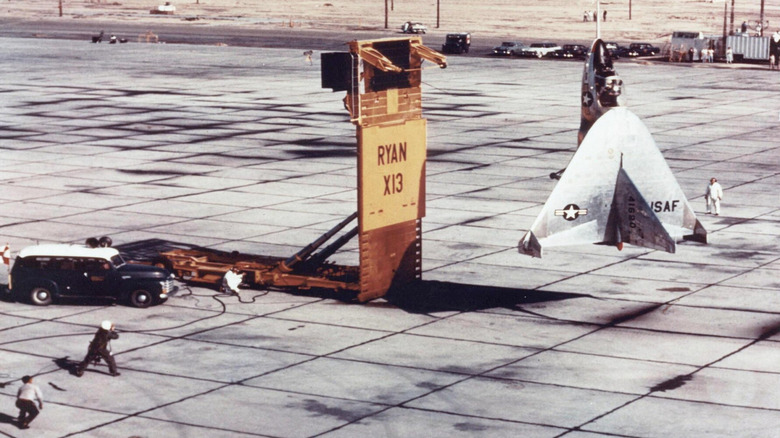

Ryan X-13 Vertijet

The Ryan X-13 Vertijet resulted from the Air Force's desire to create a proof-of-concept for a vertical takeoff and landing (VTOL) jet fighter. In the 1950s, the Air Force grew concerned that large bases were vulnerable to nuclear strikes by the Soviet Union. It perceived a need for a fighter that could operate from anywhere if major airfields were taken out. The result was a pair of prototypes for a tiny jet that could take off on its tail and land by catching a wire with its nose hook. The X-13 first flew in December of 1955, albeit with conventional landing gear bolted on until test pilots could prove the plane flew safely.

The Vertijet proved to handle well and transitioned from horizontal to vertical flight easily, so testing proceeded to the jet's intended launch and recovery method. The X-13 launched vertically from the bed of a flatbed truck, with the pilot rotating his seat 45 degrees to compensate for the plane's vertical stance. Upon landing, the jet would slow and rotate to the vertical using vectorable exhaust, and then the pilot would "walk" the aircraft a few feet at a time toward a recovery trailer until he could catch a wire with the plane's nose hook.

Needless to say, this was a complicated and difficult procedure. It required spotters on the ground to guide the pilot by radio, since even with his seat rotated to the 45-degree position, he couldn't see the ground. Funding issues contributed to the X-13 program's demise in 1958. However, VTOL flight had been proven in concept, and lessons from the X-13 would be used in designing later VTOL aircraft like the AV-8 Harrier.

Northrop YA-9A

Casual aviation enthusiasts might do a double-take upon seeing Northrop's YA-9A, given its resemblance to the legendary A-10 "Warthog" attack plane, the plane to which it lost in a competition for close air support fighter. In the 1960s, U.S. Air Force jets had evolved toward being supersonic fighters, which performed poorly in the close air support role. These fighters were too fast to linger and make pinpoint strikes, and they also weren't rugged enough to absorb ground fire. As a result, the Air Force called for a competition to build a dedicated close air support jet.

The Air Force requested a jet that could maneuver and linger at low speeds and which offered enough survivability to withstand small arms fire and rocket attacks from the enemy while flying at low altitude. In 1972, Northrop entered the YA-9A into competition. While the front end of the plane resembled its A-10 competitor, the YA-9A had engines conventionally mounted to the sides of the fuselage, and the wings were above the engines. It also had a conventional tail instead of the A-10's twin stabilizers. Like the A-10, it had a rotary cannon in the nose and multiple hard points under the wings for bombs and missiles.

The YA-9A could take off in only 2,300 feet and land in as little as 875 feet, both solid attributes for a front-line fighter. The top speed was 450 knots, but it could maneuver with one engine at speeds as low as 75 knots, which is excellent for a close air support jet. Yet ultimately, the Air Force selected the A-10 because it felt that the manufacturer, Fairchild-Republic, was further along in development.

Grumman X-29

The Grumman X-29 was a strange jet design whose configuration will probably never be seen again. Its wings swept forward instead of backward as on conventional jets, and its horizontal stabilizers (called canards), instead of being on the tail, were located ahead of the wings. Its wing configuration gave it inherently unstable flight characteristics, but engineers learned much about using computer-controlled systems to manage aircraft in flight.

NASA built two X-29 prototypes in collaboration with the Air Force and the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA). The first X-29 took flight in December 1984, and the second flew for the first time in May 1989. In addition to the X-29's fly-by-wire controls, in which computers interpreted the pilot's input on the stick and adjusted flight control surfaces up to 40 times per second, the X-29 was an advanced test bed for other technologies. It sported a composite design, novel flaps, variable-camber wing surfaces, and other unique features.

Its unconventional body created a low-drag aircraft, and its forward-swept wings' aerodynamics prevented stalling at high angles of attack. Throughout hundreds of test flights, the X-29 prototypes demonstrated that fly-by-wire controls could help pilots control jets that otherwise would be unflyable. In fact, it demonstrated high maneuverability and supersonic capability, proving that it was more than just an unusual configuration. Having proven their tech, both jets were retired and are on display at NASA Armstrong in California and the Air Force's museum in Dayton, Ohio.

McDonnell Douglas/General Dynamics A-12 Avenger II

The A-12 Avenger II, named after a World War II-era torpedo bomber, resulted from the U.S. Navy's request for a replacement for the Grumman A-6 Intruder. While delays and high costs led to the cancellation of this proposed carrier-based stealth attack jet, several of its technologies found their way into future stealth fighter aircraft. (It's important to note that this A-12 is a completely different plane from the A-12 Oxcart, the 1960s predecessor to the SR-71 Blackbird.) The A-12 Avenger II was a flying-wing design scheduled for its first flight in 1990, but it never actually flew. This is one jet that literally never took to the skies.

The proposed plane – nicknamed the "Flying Dorito" for its triangular shape – would have used that shape and advanced composite materials to achieve stealth. Its specs called for twin General Dynamics F412-GE-D5F2 turbojet engines producing a combined total of 26,000 pounds of thrust. It would have carried 5,500 pounds of armaments. At 70,000 pounds, it would be big and heavy, with folding wings for operating in the confined spaces of an aircraft carrier.

Ultimately, with the A-12 running behind schedule and way over budget, the Pentagon canceled the program in 1991 before any prototypes flew. At $5 billion spent, it was one of the most expensive weapons systems ever to be canceled up to that time. However, the engineers who worked on it drew important lessons about stealth technologies that would later shape production aircraft like the F-22 Raptor and the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter, so it still served a role as a test bed for future fighters.

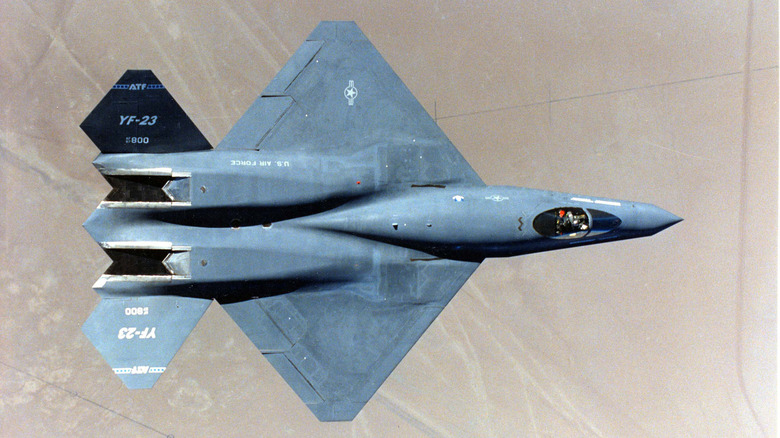

Northrop-McDonnell Douglas YF-23

The YF-23, unofficially dubbed the Black Widow II, ended up losing an intense competition with the YF-22A – the prototype for the current F-22 Raptor – to become the first stealth air superiority fighter. Yet some of the Black Widow's fans argue that when considering the strengths and weaknesses of the F-22 against those of the YF-23, the latter was actually the better plane.

Both planes were built as part of the Advanced Tactical Fighter program, which was a response to improved Soviet fighters and missiles. The new plane was intended to succeed the Air Force's then-current air superiority fighter, the F-15 Eagle, adding stealth and other capabilities that the F-15 lacked. To that end, the YF-23 employed a wing profile that resembled a diamond when seen from above or below, since tests showed that this shape minimized its radar profile. Radar-absorbing materials and thermal management lowered its profile even further. Testing showed that it could reach Mach 2.2.

However, the YF-23's designers opted against thrust vectoring, which redirects exhaust from a jet's engines to increase maneuverability. Its competitor had this feature, which may have been a major reason the Raptor beat the Black Widow to win the Air Force contract. Also, Lockheed, which built the F-22, may have simply done a better job of selling the Air Force on its program. A later attempt to develop the YF-23 into a bomber never bore fruit.

Boeing X-36

The full name of Boeing's X-36 was the Tailless Fighter Research Agility Aircraft. Like the X-29, it was a test bed for advanced concepts rather than a prototype for a proposed future fighter. In fact, this unmanned plane was barely over a quarter of the size of any likely fighter that could be based on it. First flown in 1997, it demonstrated the power of flight control software to tame an inherently unstable design and give the futuristic jet incredible agility. Lacking a tail section increased aerodynamics and reduced the plane's radar cross-section, making it an excellent way to test designs for future fast and stealthy jets.

The X-36 only weighed about 1,250 pounds and had a wingspan of merely ten feet. Its single engine generated only 700 pounds of thrust. A nose camera and onboard microphones allowed a remote pilot with a head-up display to control the plane. It was effectively a drone in today's terminology. It allowed NASA, Boeing, and the Air Force to test a tailless configuration on a fighter jet form factor for the first time. Its neural network software had a reconfigurable control algorithm that enabled multiple software configurations to be tested. This was used to find the best flight control algorithm and to test ways to compensate for hypothetical battle damage, and 31 test flights proved the success of the X-36 concept.

Boeing X-32

The X-32 was Boeing's entry into the competition to build a Joint Strike Fighter (JSF), which was ultimately won by the Lockheed Martin-built F-35 Lightning II. Although it failed to win the JSF contract, the X-32 made a good showing in the contest. Boeing designed three variants: a conventional fighter/attack jet for the U.S. Air Force, a carrier version for the Navy, and a short takeoff and vertical landing (STOVL) version for the Marines. Two X-32s were built, with the first prototype flying for the first time in September 2000.

The X-32 could charitably be considered an ungainly-looking aircraft, with a huge, angular engine intake leading to a swollen belly. Yet despite its less-than-sleek profile, tests suggested that its stealth signature was similar to the F-35. Power came from one Pratt & Whitney F119-614C engine producing 35,000 pounds of thrust. Range for the X-32A (the Air Force variant) was a very respectable 1,700 nautical miles. Top speed was Mach 1.5 or 1.6, depending on the source. It could carry comparable weapons loads and electronic equipment compared to the F-35.

The X-32 would probably have made an effective and stealthy fighter that approached or equaled many of the F-35's advanced battle capabilities. Yet the Pentagon ultimately preferred the F-35's turbolift engine in the vertical takeoff variant over the X-32's vectored thrust, and it felt that Lockheed's experience in building the F-22 Raptor gave it an edge. Therefore F-35 went on to be the largest weapons program in history, leaving the X-32's backers to wonder what might have been.