Why Pepsi Once Had More Submarines Than Most Countries

News headlines in 1989 pointed to a world on the brink of upheaval: tanks rolled through Tiananmen Square, East Germans rejoiced as they wrenched down the Berlin Wall, and Tim Berners-Lee debuted a hypertextual information management tool called the World Wide Web. But perhaps no headline is more emblematic of its time than Pepsi Co.'s purchase of twenty Soviet warships. How an American company came to own the world's sixth-largest naval fleet is even more riveting than the headline once you place it in its proper context.

Twenty years in the making, the story behind Pepsi's military submarines involves a host of unlikely characters, including Richard Nixon, Russian Vodka, pizza sauce, Henry Kissinger, a thirsty Nikita Khrushchev, and a smuggled transistor radio. The central character, however, was Pepsi executive Donald Kendall, whose rise from bottling plant employee to CEO enabled the company to not only peak behind the Iron Curtain but surpass it completely. All this culminated in one of the strangest moments of the "Cola Wars," in which Pepsi deployed every tactic in its political and economic toolboxes to achieve its goals towards global hegemony — and accumulated a navy in the process.

Escalating the Cold (beverage) War

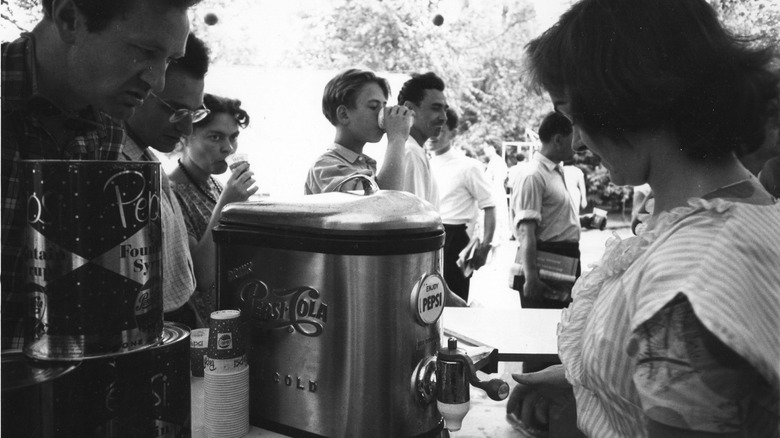

Pepsi's Russian venture began when President Eisenhower organized the 1959 American Exhibition, inviting companies like Kodak, Disney, and IBM to showcase their products for six weeks at Moscow's Solkoniki Park. Vice President Richard Nixon also headed the event. A fierce anti-communist, Nixon escorted the Russian leader Nikita Khrushchev through various stalls before engaging him in a heated discussion, now known as the Kitchen Debate. In typical Cold War fashion, the ensuing media frenzy left both sides believing themselves the victors, with Khrushchev and Nixon's approval ratings surging. But no one experienced as much of a boon from the debate as Pepsi.

As the story goes, Pepsi executive Donald Kendall — a close friend of Nixon's — used his relationship with the Vice President to place him near the heat of the action. Seeing Khrushchev mopping the sweat off his brow during the debate, Kendall hurried over with an ice-cold Pepsi, scoring an advertising coup that would sow the seeds for a future jump into the Soviet market. Unfortunately, it would be over a decade before the move paid dividends, as escalating tensions between the two nations nixed any possible deals for the Cola brand.

When Kendall became the CEO of Pepsi four years later, he found himself tasked with a single mandate: Win the Cola War. The task was, admittedly, monumental. At the time, Coca-Cola's global sales were three times that of Pepsi's. Kendall approached the problem with an international mindset. In his first year on the job, the Cola company added 34 international bottling locations. And in the half-decade following, the soda company doubled its global presence, retailing in 120 countries. However, one elusive trade partner remained, and Kendall believed it would propel his company past its rival for good.

The Soviets pick a side in the Cola War

Kendall used more than his improvised marketing coup to solve the Soviet problem. He also won and utilized the favor of newly elected president Richard Nixon. Nixon's connection to Pepsi is typical of the quid pro quo expected from Washington — and yet, is something we tend to overlook when tracing the history of international maneuvering. After losing the presidential and California gubernatorial elections, Nixon desperately needed a rebound.

In an ingenious move of capitalist statecraft, Kendall linked the procurement of Pepsi's legal services with the Vice President's job prospects, landing Nixon a position with the New York law firm Mudge, Stern, Baldwin, & Todd. The job both filled the vice president's pockets and laid the groundwork for his political comeback. When Nixon beat Hubert Humphrey and George Wallace in the 1968 presidential election years later, Pepsi gained an ally in the White House, paving the way for Kendall to move in on a market he'd been eyeing ever since the American Exhibition: the USSR.

12 years after his initial push, Kendall finally made his move. At the time, the Cold War was at a critical juncture, with the Berlin Wall, Vietnam War, and Cuban Missile Crisis all pushing U.S.-Soviet relations to the limit. So in 1971, the Nixon administration came to the negotiating table with a typically American peace offering: A trade delegation featuring — you guessed it — Donald Kendall.

Through a series of ingenious moves, including a Pepsi-shaped transistor radio and a friendly call from the office of Henry Kissinger, Kendall made Pepsi the exclusive exporter of American soft drinks to the Soviet Union. One hurdle remained, however — and its solution would lay the groundwork for the infamous soda-for-subs swap almost two decades later.

Show me the money

So, what stood in the way of Kendall's dreams? The Russians had a cash problem. Rather, Pepsi had an issue with the Russian Ruble, which couldn't be traded on foreign markets. To solve this problem, Pepsi orchestrated what is known as a "countertrade," essentially allowing the Soviets to pay for Pepsi sodas with a commodity rather than cash. Bartering agreements were a common practice for the USSR in its international business deals in 1971. For example, even the Swedish band ABBA would receive its royalty checks in the form of oil and food goods.

So what did the Russians offer Pepsi in this initial venture? A drink of their own, vodka. As such, Pepsi became the official U.S. importer and distributor of Stolichnaya Vodka, making it the first company to bring authentic Russian vodka stateside since Prohibition. A little discussed sweetener of the relationship was the addition of Russian tomato paste, which Pepsi used in its Pizza Hut locations across Europe.

This one-for-one swap had its long-term limits. Despite being the only premium Russian vodka on the market, Stolichnaya's sales were susceptible to the ebbs and flows of Russia-U.S. relations. By 1976, it amounted to only 1% of the US vodka sales market. So when Pepsi looked to scale up its presence in the Soviet Union, Kendall knew a different swap would need to be brokered.

Is soft drinks for a navy a fair trade?

The late 1980s saw great changes across the Soviet Bloc. Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev ushered in a new wave of political and economic openness, welcoming Western investment while encouraging a more politically open system of governance. Several American brands had dipped their toes into the Soviet market as a result, with companies like McDonalds, Honeywell, Baskin-Robbins, and Pizza Hut (owned by Pepsi Co.) all forming joint ventures in the country.

With that being said, Pepsi still dominated the USSR's cola market, producing a billion servings across 21 bottling plants annually. Coca-Cola, in contrast, was only available in touristic novelty shops despite serving as the official drink of the 1980 Moscow Olympics. But for all its Soviet success, Pepsi still languished behind its arch rival in global sales, and needed a competitive advantage.

For his part, Kendall continued to believe that the Soviet Union was Pepsi's golden ticket, with the superpower sitting on the eve of what many thought would be an era of economic prosperity. Pepsi wanted to more than double its presence in the country, adding 26 bottling plants and two Pizza Hut locations. The only problem? Despite the increased presence of Western investments, the Ruble's international prospects had not improved. McDonald's, for example, had to spend millions of dollars to solve its foreign exchange problems when opening its Pushkin Square location.

Luckily, Pepsi already had a blueprint, but this time, vodka and tomato sauce couldn't cover the billion-dollar price tag. To diversify their offering, the Soviets sold the Cola manufacturer 17 submarines and a collection of warships. On paper, the deal tied Pepsi with India for the 7th largest fleet of military submarines.

Oil, warships, and soda: a new currency

So, what did Pepsi do with its fleet of warships? Did it blockade Coke's shipping centers or plunder freighters stocked with Dr. Pepper? Per usual, the historical reality hardly lived up to our conspiratorial imaginations. Instead, Pepsi's answer was to scrap them. At the time, the Soviets often sold unseaworthy vessels for parts, scraping nearly 1,000 warships over a decade. In fact, this controversial practice was so common it halved the price of scrap metal in Europe during the '90s.

U.S. and European policymakers were skeptical, even outraged with the practice, citing concerns that it enabled the Soviets to modernize their military. However, for Pepsi, the deal made all too much sense; replacing the volatile Ruble with a tangible commodity. Furthermore, the fleet amounted to a mere trifling of the total sale, as decommissioned Russian Whiskey submarines could be had for as little as $50,000 in 1990. Instead, a different kind of ship interested Pepsi: oil tankers.

Partnering with two Norwegian companies, Pepsi Co. traded for 85 Russian oil tankers worth nearly $2.6 billion —roughly $82 billion in today's currency. The Norwegians facilitated the deal by scrapping the military vessels and leasing the tankers for their Cola partners. The Soviet Union, in turn, increased its Pepsi bottling locations to 50, and saw an overhaul of its shipyards. As Kendall put it during a company press conference, it was "the largest and most wide-reaching agreement ever signed in the field of consumer goods."

A deal breaks apart

When the Soviet Union collapsed in December 1991, it took much of Kendall's deal with it. As he said in an interview years later, "All of a sudden, the whole thing was in pieces — hundreds of pieces." The dissolution of the Soviet Union posed a major logistical problem for Pepsi.

Suddenly, the various parts of their supply chain were spread across several countries. The ships were assembled in Ukraine, the plastic bottles made in Belarus, and their contents poured in Russia. Looking back, Kendall described it thus: "We had a multibillion-dollar contract with a nonexisting entity — the Soviet Union." Within a few years, Coca-Cola overtook its rival's Russian market share. Ironically, a U.S. president struck the final blow in the company's Russian "failure" when Bill Clinton chose to visit Coke's $65 million manufacturing plants over Pepsi's during his visit in 1995. The visit signaled the end of Pepsi's Eastern Bloc supremacy.

Donald Kendall didn't fully lose out on his Eurasian dreams, however. Fifteen years after the deal, Vladimir Putin gifted the CEO with the Order of Friendship for his contributions to the Russian economy. When he passed away in 2020, Russia was still Pepsi's third biggest market, generating a whopping $3 billion annually.

The picture, however, became more complicated when Russia invaded Ukraine, with both Pepsi and Coke announcing their withdrawal from the country last year. As such, projecting the two soda giants' muscovite futures is difficult. Whether or not these soda companies return in the near future, however, hopefully it won't involve the exchange of warships to make it happen.