10 Inventions You May Not Have Realized Came From Leonardo Da Vinci

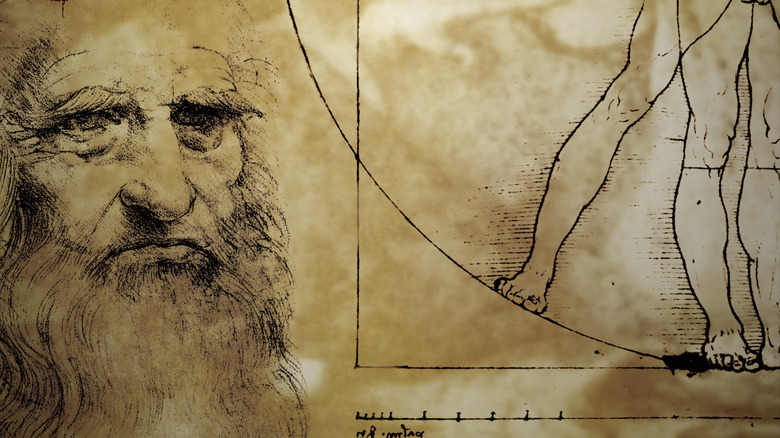

Leonardo da Vinci was a genius of the ages, born to unwed parents near Florence, Italy, in 1452. Davinci's mother soon married another man, leaving young Leonardo to grow up on his biological father's estate, where he was treated as a legitimate son and received the standard education of the day.

Reading, composition, and mathematics classes formed the foundation of future intellectual endeavors, but Da Va Vinci considered his eyes the best tool for acquiring knowledge. He operated under a concept known as "saper vedere" — knowing how to see.

As an adult, Da Vinci split his time between Florence, Venice and the city most closely associated with his work, Milan. Under the patronage of the powerful and wealthy, he conceptualized, designed, and created masterpieces ranging from the Mona Lisa to the machine gun.

A pair of his most famous concepts, the helical air screw and an armored mobile gun platform, were so advanced it would be centuries before humanity was capable of producing a working helicopter or tank.

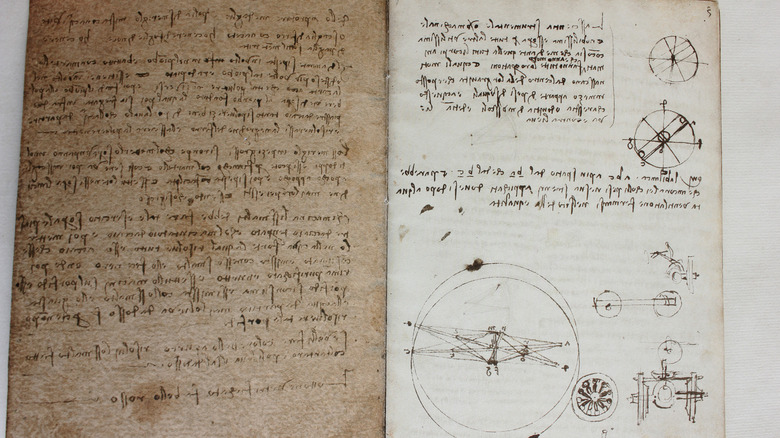

Da Vinci left thousands of pages of journals upon his death in 1519. For centuries, academics have scrounged those pages, uncovering dozens of designs, some built, others left theoretical, that would profoundly impact humanity.

In honor of one of the greatest geniuses of all time, we examine 15 inventions you may not have realized come from Leonardo da Vinci.

Pedometer

In an era where precision was rare, Da Vinci's dedication to measurements was unparalleled. Whether it was the intricacies of time, which he addressed with his design of a more accurate timepiece, or the exacting tolerances of his mechanical designs, Da Vinci's sought to measure the world with utmost precision.

His invention of a device for measuring the distance a person has traveled stemmed from his work developing military devices for the Duke of Milan, a powerful figure in Renaissance Italy. The duke's interest in military technology gave Da Vinci the resources and motivation to create innovative solutions.

A device that could accurately track distance traveled could gain valuable information regarding a soldier's position and capabilities, a fact not lost on Da Vinci.

He tackled this issue by designing a device that could measure how far a person walked. Now commonly known as pedometers, his mechanical device was worn at the waist. A pendulum rocked back and forth with each step, activating gears that counted the distance a person walked.

Although the device was never realized in Da Vinci's time, it is a testimony to his advanced mechanical thinking.

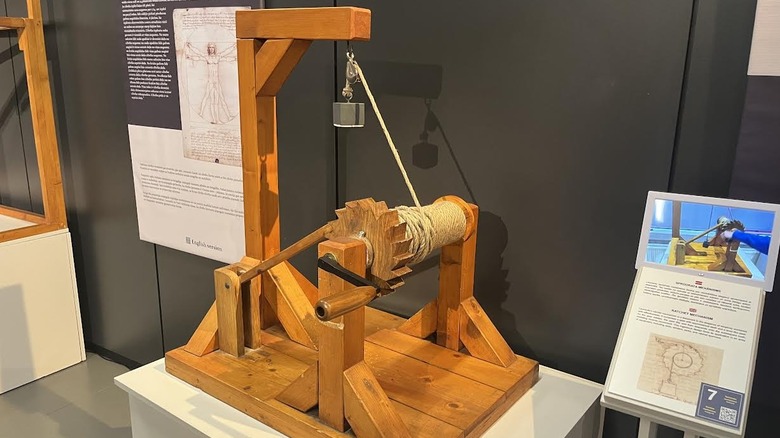

Scaling ladder

Sieges were still a significant part of warfare in Da Vinci's day. Though the Renaissance ended the medieval era, the city-states of the Italian peninsula still had to consider placing an enemy under siege as a battle tactic. The cities of the day were built with tall, near-impregnable walls. With a decent supply of food and water, besieged cities could hold out for months or years — often long enough for an ally to come to their aid. Militaries devoted considerable effort to producing weapons like the trebuchet for siege warfare.

Da Vinci designed a scaling ladder to reduce the challenge of breaching cities. Placing a ladder against a city wall and climbing it under combat conditions is intensely dangerous. Even getting ladders close enough to the wall under a rain of arrows and boiling oil was a potentially mortal challenge.

This fast-deploying siege ladder system operated using a hand crank and gears, allowing a military force could deploy it in moments, all the while maintaining an angle that made it easier to climb and more difficult for defenders to pour fire on the attackers. Da Vinci viewed war as a monstrous business, and therefore might find solace in the fact that his concept is now a global lifesaver as a integral part of a fire department's arsenal.

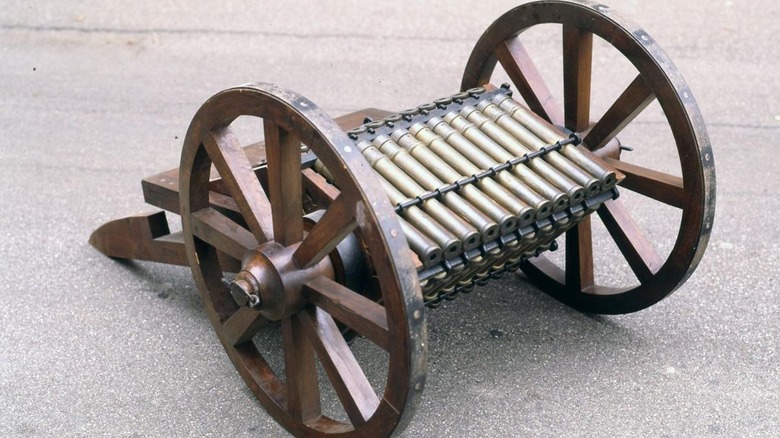

Machine(ish) gun

Da Vinci lived when firearms were increasingly prominent, but they had not yet supplanted traditional war methods. Despite his aversion to war, many of Da Vinci's concepts revolved around it as he was the chief military engineer of Milan for a time.

Artillery would ultimately spell the end of the age of knights and sieges. Increasingly powerful and accurate long range guns could smash a city's wall down, making quick work of what would have previously taken months. However, early firearms presented enormous advantages in ranged fighting, but also suffered drawbacks, not the least of which were ponderous reloading procedures. The time it took to reload a cannon reduced an army's fire rate and gave the enemy time to seek cover or even overrun a position.

Da Vinci proposed a contraption to keep steady fire raining down. Known as the "33-Barreled Organ," his 1481 design incorporated three rows of gun barrels set on a wheeled carriage. Upon firing the first row of pre-loaded barrels, the apparatus rotates, presenting a fresh set of barrels for firing while the gun's crew loads the empties.

Though differing in fundamental operation, Da Vinci recognized that a fast-firing gun could be one of the most dangerous military weapons ever to grace the battlefield.

Scaling wall defense

Da Vinci's war machines were not purely offensive. While pondering the question of siege ladders, a common and effective tool used in medieval warfare to breach city walls, he also struck upon a defensive measure a soldier might use to prevent one's use against him.

His wall defense system included a machine built of wooden beams and gears incorporated into the walls of a city. Defenders of a town facing siege ladders could activate a mechanism that would push a solid beam away from the top of the outer wall. Any siege ladders (unless they happened to be of Da Vinci's unbuilt scaling ladder design) would be pushed away from the wall, unseating the attackers.

Da Vinci envisioned the base of the contraption several feet above the heads of the attackers, a strategic move that would prevent them from disarming or dismantling it from the outside. Like many of his ideas, this one was never used in warfare. However, it showcases Da Vinci's mastery of mechanics and an ability to attack a problem from any conceivable angle.

Wheellock

The earliest firearms relied on matchlock operation. An s-shaped mechanism called a serpentine held a lit match or wick. When a soldier depressed the trigger, the serpentine fell forward, pressing the flame into a flash pan next to a hole in the breech, igniting the gunpowder, and firing the weapon.

Keeping a flame at hand was a significant challenge in the days before lighters and chemical matches. The system's fragility meant damp or windy weather often snuffed the fire, and the open flame could give away a fighter's position in the dark, highlighting the urgent need for a more reliable system.

The updated design worked on a principle similar to that of a Zippo lighter. The trigger spun a flint wheel against a piece of ridged iron, igniting the powder with a shower of sparks. Requiring the fine milling of metals, the wheellock mechanism was far more expensive to produce than the less reliable matchlock.

Scholars found several sketches of wheel lock mechanisms in Da Vinci's journal, but some argue that the genius may have been caught up in a matter of simultaneous invention. Firearm factories in Augsburg and Nuremberg in lower Germany began producing them around the same time as those in upper Italy at Milan, Genoa, Bologna, and Venice.

Scholars still debate over who deserves credit for the advent of the wheellock, but Da Vinci's journals prove that he conceptualized it right around the time it began production.

Driverless carriage

Karl Benz rightfully owns the claim to the first car ever invented, but Da Vinci's sketches included yet another example of thinking that outpaced technology. His driverless carriage design was centuries ahead of steam and internal combustion engines, and yet it was able to move under its own power.

Scholars discovered a series of diagrams in Da Vinci's journals that showed he worked on the concept between 1478 and 1485. Engineers, dedicated to unraveling the mystery, puzzled over the schematics for decades to deduce how the carriage generated power. With the sketches and modern technology, engineers and designers from the Institute and Museum of the History of Science in Florence, Italy, invested eight months to recreate a ⅓ scale working model.

The cart, using springs that wind up by pushing the cart backward, was a marvel of its time. The wheel's motion increased tension in a spring mechanism on the underside, and when released, the cart could travel under its own power — not unlike the toy cars you may have played with as a child. However, the limitations of the era meant that the cart could only travel a distance of a few meters before petering out, explaining why the age of the automobile didn't dawn in the 15th century.

The driverless carriage couldn't beat good old horsepower. With such limited utility, it was likely intended as little more than an ingenious stage prop or curiosity.

Diving suit

Whether sending people into the sky or under the sea, Da Vinci seemed preoccupied with putting human beings in new places.

Living in Venice after a French invasion ejected him from Milan in 1499, Da Vinci was acutely aware of the threat of attack by sea. Ottoman naval forces frequently menaced the Mediterranean coasts, prompting Da Vinci to devise a potential way to tilt the odds in favor of the weaker Venetian navy.

While naval warfare evolved to include the submarine much later, Da Vinci devised an apparatus to supply a submerged person with air so that they might damage encroaching ships from the underside. The enclosed leather suit included an inflatable bladder filled or emptied of air via a valve to help divers sink or float. A hose attached to a mask led to the surface, where the open end bobbed on a small buoy made of cork, thus supplying the submerged person with air. Da Vinci even devised a pouch for collecting urine during extended submersion.

The concept of Da Vinci's diving suit, though not so different from the diving suits humanity began to use hundreds of years later, was undoubtedly dangerous. The fact that the Venetian navy was able to drive off the Ottomans before it had to take such desperate measures is probably a good thing for some lucky sailors.

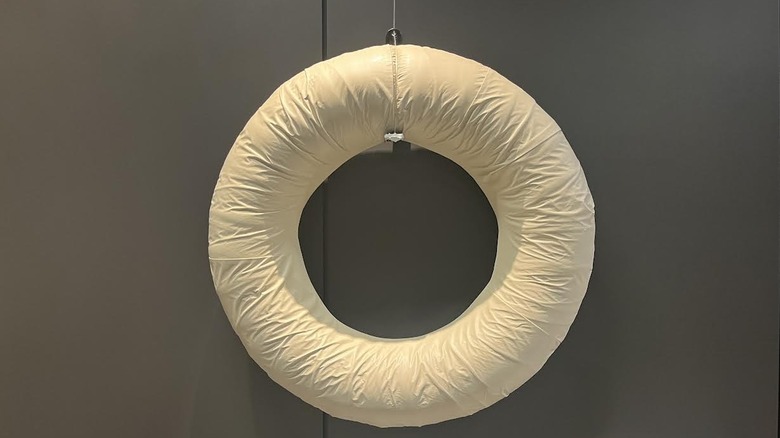

Life belt

Imagine Venice in Da Vinci's day, a city built across around 120 islands divided by endless canals. Aptly nicknamed "The Floating Marvel," it was a sight to behold. Though smaller in scale, it was not much different from present-day Venice. Water abounded in the canals, lagoons, ports, and bays of the marshy land north of the Adriatic Sea.

Da Vinci developed one of the earliest designs for a piece of safety equipment that was genius in its simplicity: the life belt. Ubiquitous on the rails of seagoing vessels and beside bodies of water worldwide, modern humanity is so accustomed to it that it's hard to imagine someone needing to invent it.

Sketched in 1485 while still happily ensconced in Milan, Da Vinci's journal shows a design that was not just innovative, but also incredibly practical. His life belt incorporated inflated pockets of air lining a ring that could slip around a drowning swimmer's waist. A bonus was that it could be thrown to a victim, thus eliminating danger to any would-be rescuers.

Like so many of his ideas, there is no evidence that Da Vinci ever built the life ring, but even with the advancements in materials and scientific knowledge, modern life belts work on similar principles.

Ratchet

Next time you use ratchet straps to secure something, take a moment to appreciate the practical genius of Da Vinci. His experiments with metallurgy and opposing forces led to the development of a simple yet effective method of tension retention, a method we still use today.

Da Vinci's use of gears was a game-changer. Whether it was his driverless carriage or wheellock mechanism, he had a unique ability to create new applications with existing technology. The earliest gears can be traced back to ancient Chinese chariots, dating as far back as 3,000 BCE.

Da Vinci's method of tension retention was a masterpiece in itself. He used a curved bar, known as a pawl, in combination with a gear with specially shaped teeth. A spring was used to maintain tension between the pawl and the gear. When the gear was turned in one direction, the pawl engaged with each tooth, and when the gear stopped, the pawl prevented it from moving backward. This ingenious system has been used in everything from zip ties to impact sockets.

Mirror Writing

The world was not particularly accommodating to left-handed individuals in Da Vinci's era. Perhaps this is why the southpaw genius honed a unique skill: mirror writing. Da Vinci's notebooks, numbering in the thousands, present a fascinating challenge for scholars due to his predominant use of mirror writing.

Da Vinci painstakingly crafted each letter in reverse, ensuring that it was perfectly legible when viewed in a mirror. The reasons behind this unique practice are a subject of speculation, adding to the mystery of this Renaissance genius.

Some theories venture that Da Vinci wrote backward so that he would avoid smudging his work — the ongoing struggle of lefties everywhere. That might seem like a lot of work with little payoff, but considering the fine details in his sketches, which included copious designs that depended on intricate shading and precise lines, keeping ink un-smudged would be paramount.

Others claim he may have done this as a security measure. His notebooks were filled with valuable and unique ideas that might seem dangerous to authorities or interesting to foreign parties. Anyone looking at his notebook could make little sense of it without discerning the secret.

Another theory postulates that he may have used the laborious style to slow down his thinking and better examine his ideas — a sign of a brain in overdrive if ever there was one. Whatever the case, Da Vinci almost exclusively used mirror writing, only switching to a typical script when writing for the consumption of others.