12 Strange & Bizarre Microsoft Products You Probably Didn't Know Existed

When we think of Microsoft, many of us will immediately think of the Redmond, Washington corporation's big hits — Microsoft Windows, Microsoft Office, and the Xbox. However, while these products may be the most recognizable ones to bear the Microsoft name, they're far from the only products the corporation has released over the decades.

Microsoft has been around since 1975, and its growth follows that of the personal computer. So, it shouldn't come as any surprise that the corporation has had a bunch of software and hardware offerings over the years that have fallen through the cracks. Some of these products flopped because they were bad, while others were just too far ahead of their time to be successful. Others are just perfect snapshots of 1980s and 1990s technological quirkiness, the sort of fun tech products that are so of their time that it's easy to forget them — and which we likely wouldn't associate with the Microsoft we know today.

So, without further ado, here's a list of 12 strange, bizarre, and likely forgotten Microsoft hardware and software products from the past few decades. How many of them do you remember?

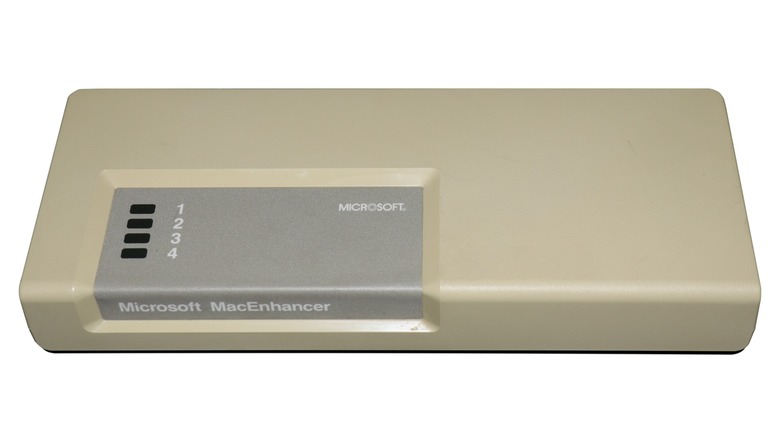

Microsoft MacEnhancer

Unless you're a real nerd — or are old enough to have used PCs in the 1980s — then you're probably not aware that Microsoft once made several bits of hardware for Apple Macintosh computers. That's right, despite the two companies being rivals in the desktop PC realm in the modern era, the Redmond corporation spent the 1980s releasing expansion cards and hardware for Macs. One of these, and possibly the most relatable, was the Microsoft MacEnhancer.

The MacEnhancer came out in 1985 and was a small beige box that connected to the Apple Macintosh 128K's modem or printer ports, expanding the computer's connectivity with an IBM PC-compatible parallel and serial ports. This, as contemporary magazines reported at the time, allowed Macintosh owners to create graphics and then send the images to be printed on IBM PC-compatible printers. Why was this necessary? Apple essentially only had one printer out at the time, the LaserWriter, while PC users had a ton to choose from.

MacEnhancer owners could also connect to modems and other serial or parallel port accessories designed for the IBM PC, opening up a whole world of peripherals that would otherwise have been closed off to Mac owners. In fact, you could say that the MacEnhancer was a very early predecessor to all the MacBook docking stations available on the market now. The more things change, the more they stay the same.

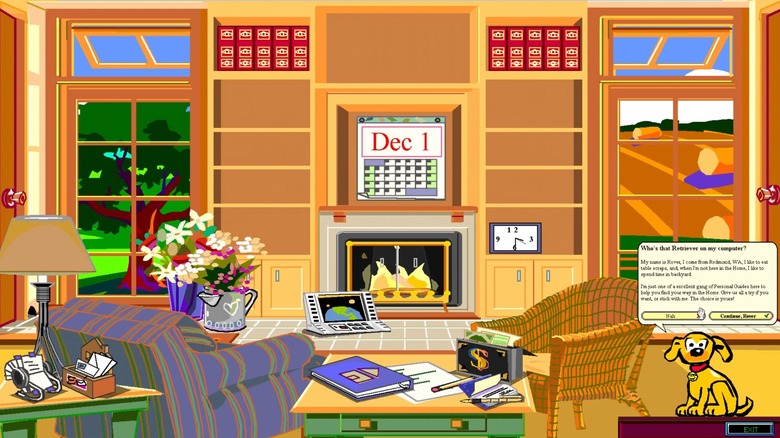

Microsoft Bob

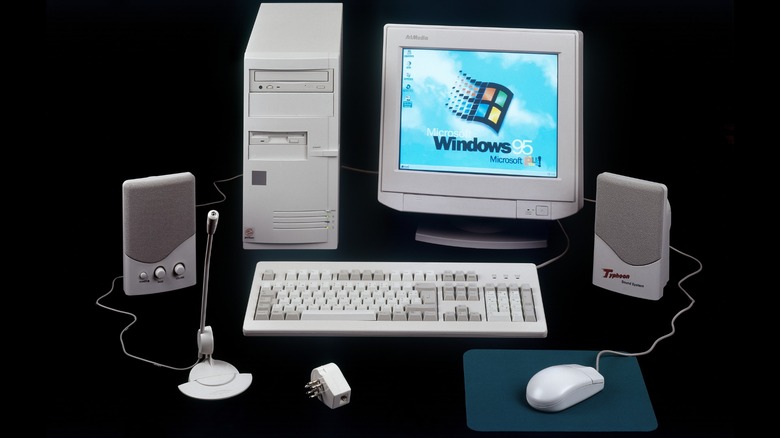

The idea of a beginner-friendly interface for an operating system probably seems terribly quaint in 2024, but that's precisely what Microsoft felt it needed to offer to users back in March 1995. Say hello to Microsoft Bob, possibly one of the biggest missteps the company has ever made.

Microsoft Bob was Microsoft's attempt at simplifying the Windows 3.1 user interface, replacing it with a cartoon house users navigated as if in an adventure game. Clicking on certain objects would open up the associated program, and you could further customize these rooms by adding new objects (in other words, shortcuts). Bob even had a guide called Rover, who would chime in and help you navigate the house, a precursor to the infamous Office Assistant known as Clippy.

If you're old enough to remember Windows 3.1, you'll probably understand why a simplified user interface wasn't an inherently bad idea. However, high system requirements, an overly cute delivery, and a $100 retail price combined to ensure Bob was a failure. Microsoft arguably put the final nail in Bob's coffin when the company launched Windows 95 a few months after Bob, with the OS debuting a new, user-friendly, graphical user interface with the now-ubiquitous Start button and taskbar. Bob's days were numbered, and Microsoft discontinued it barely a year after its launch.

Microsoft EasyBall

Bob wasn't Microsoft's only attempt to make computing child-friendly in the mid-90s. The company also released the Microsoft EasyBall, which debuted in 1995. The EasyBall was a pointing device designed for children aged two to six — essentially a large yellow ball in a beige plastic frame, the EasyBall simplified movement by allowing kids to move an on-screen cursor without worrying about physically moving a mouse. It was a minimalistic affair, with no capacity for right-clicks, but that wasn't likely a big issue for its target audience.

Parents who purchased an EasyBall for their children got more in the box than just the device, too. Microsoft bundled the pointing device with child-focused software. One 1995 ad lists the EasyBall as coming with a copy of Microsoft Explorapedia: The World of Nature, while an archived version of Microsoft's old Microsoft Hardware website says that it also came with two games. These were "Microsoft EasyBall Pointerland" and the adventure game "Freddi Fish and the Case of the Missing Kelp Seeds."

Contemporary research seems to have backed Microsoft's kid-friendly claims up, too. A 1995 study indicated that the EasyBall was the preferred input device amongst a 44-child test group. So Microsoft was probably on to something with the EasyBall, although its still hard to call the EasyBall a success. Still, modern trackballs are great for adults, too, of course, and they are some of the best ergonomic mice on the market.

Microsoft ActiMates

The EasyBall wasn't the only child-focused product that Microsoft produced in the mid-to-late 1990s. Say hello to the Microsoft ActiMates, a range of interactive plush toys it developed in collaboration with PBS, who also provided Microsoft with the licenses to various hit children's TV shows.

Microsoft launched the ActiMates range in 1997 with a plushie of the most recognizable purple talking dinosaur from the 1990s, Barney. The big selling point of the Barney plush toy was that it could interact with a TV program or videogame, praising the child for completing tasks in a videogame or asking them questions based on the episode of Barney they were currently watching. This wasn't magic, though, and parents would also have to invest in separate hardware — a TV or PC RF transmitter — and play ActiMates-compatible VHS tapes or games for the system to work.

The Barney ActiMates thankfully also worked standalone, with the ability to respond to touch and a 2,000-word vocabulary, including the ability to sing "I Love You," along with a handful of other tunes. This was undoubtedly some comfort to parents given how expensive the whole system was — the toy cost $109.95 on its own, while the TV and PC transmitters were $64.95 each. VHS tapes were $14.95, while CD games were $34.95 — all in 1997 money. Barney did well despite that, though, and the two corporations followed it up with ActiMates for other franchises such as Teletubbies and Arthur.

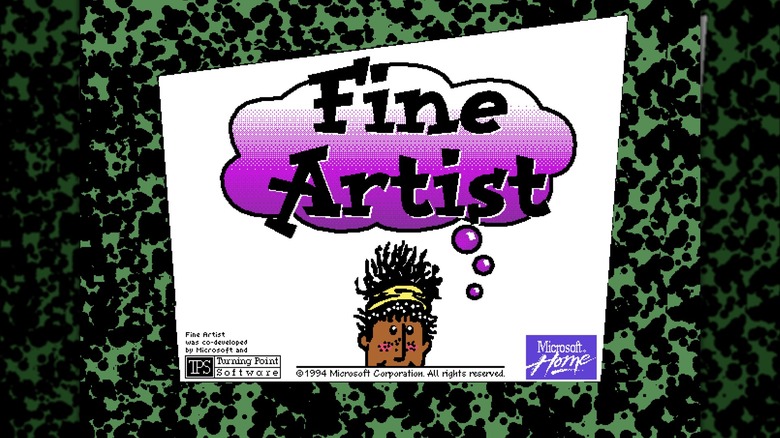

Microsoft Fine Artist

Before trying to turn its entire OS into a child-friendly experience with Bob in 1995, Microsoft tried to tap into the child software market with Microsoft Fine Artist. Fine Artist was a children's computer paint program that swapped the company's typical business-like interfaces with a colorful videogame-like UI.

Still, Fine Artist did more than slap a funky UI onto a conventional paint program. Fine Artist was also videogame-like in its design, with a fictional city called Imaginopolis that guided users through the creative process. Users explored a building that introduced them to different art and drawing skills, tips, and tricks. Users could paint freestyle, play around with brushes and stickers, apply sound effects, and create slideshows. It even taught kids about painting tricks and techniques such as negative space and vanishing points, which is commendable even now.

As you might expect, Microsoft included three guides to help children on their way — Maggie, Max, and the purple-skinned McZee, the first of the three you meet. 1990s Microsoft loved its virtual assistants, that's for sure.

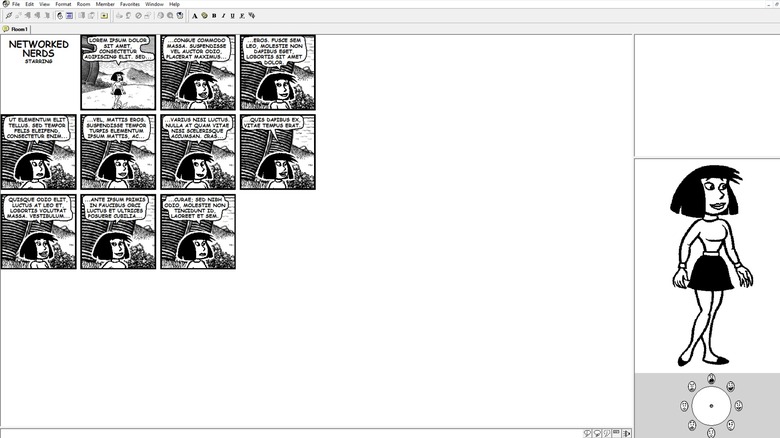

Microsoft Comic Chat

1990s Microsoft is quite interesting to look back on. On the one hand, we have industry-defining, all-business moments like Windows 95, which came onto the scene in the middle of the decade and changed the way most of us use computers. On the other hand, we have quirky experiments like Comic Chat, which the company released in 1996.

Chatting over the internet wasn't anything new in 1996. Usenet had been around since 1979, predating even the internet as we know it, while Internet Relay Chat (IRC) had existed since 1988. So Microsoft wasn't inherently doing anything new by allowing users to talk to each other over the internet. What was new, though, was the medium — comics.

Microsoft Comic Chat essentially auto-generated a comic strip based on people's chat messages. Each user could choose — and, later, create — an avatar and a background, and Comic Chat would do the rest. It seems like a bit of a silly way to chat now, but it's certainly unique and those who used it at the time also have very fond memories of it. Comic Chat survived for quite a while, with Microsoft shutting its servers down in 2001. Like the next Microsoft chat experiment, though, it lives on — you can still run the client in a modern Windows machine and connect to one of the small handful of Comic Chat-specific IRC servers running as of 2024.

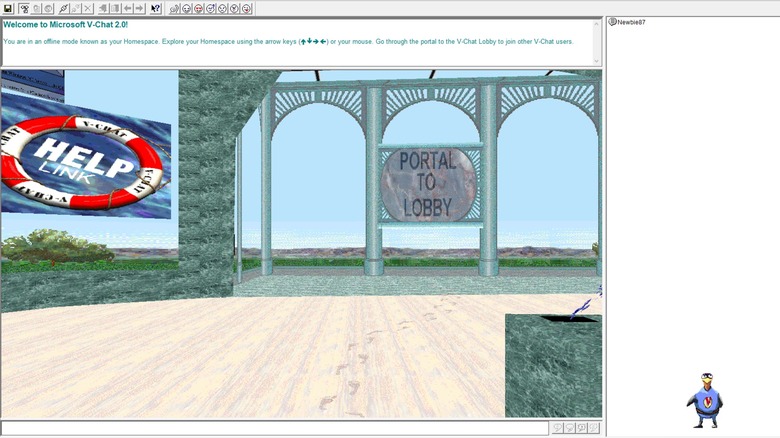

Microsoft V-Chat

Comic Chat wasn't Microsoft's only unique take on internet chat. Microsoft V-Chat, which first emerged in 1996, took Comic Chat's 2D comic strips one step further. Instead of a flat comic strip, V-Chat created virtual worlds, where users could move around, chat, and interact with each other. Think of VRChat but decades before and you're on the right path.

V-Chat was a product of Microsoft's Virtual Worlds Group, which focused on developing novel ways for people to interact with each other via the internet. The chat client allowed users to navigate 2D and 3D environments, such as Bug Land, the movie-focused Cinemania, and a café. Within these environments, users interacted with other V-Chat users via their chosen avatars, each with a limited range of actions that we would nowadays probably call emotes. Avatars could wave, smile, shrug, and even flirt, according to a report of the time.

The initial public version of V-Chat debuted in early 1997, only ran on proprietary V-Chat servers. However, V-Chat 2.0 used standard IRC servers much like Comic Chat. This let users communicate with those not using V-Chat, although the latter would get garbled text in place of V-Chat-specific features such as avatars and gestures. Spiritual successors like VRChat mean there's arguably little reason to revisit this obscure slice of internet chat history, but those of you who want to can still do so because V-Chat still runs on modern Windows PCs and there are even a couple of IRC servers to connect to.

Microsoft Kin

The mid-to-late 2000s was a heady time in tech, especially when it came to mobile communications. Apple's iPhone came out in 2007 and revolutionized the world of mobile phones, while the rise of a phone-first generation signaled the emergence of a new and lucrative market – wireless youth. Microsoft, as you may expect, tried to muscle its way into the market with the legendary flop that was the Microsoft Kin.

Microsoft's Kin was a line of two feature phones, the Kin One and Kin Two, released in collaboration with Verizon. Both were BlackBerry Slider-style phones that had 2.7- or 3.5-inch screens and a physical keyboard that slid out from below the screen. The whole idea with Kin One and Two was that they would allow teens to stay connected to each other through social media networks using dedicated features for sharing life updates to select friends or publicly, with Microsoft's servers handling all the nitty-gritty of getting that info out.

Unfortunately for Microsoft, the Kin was a terrible failure. One of the main reasons was likely the prohibitive price of the mandatory data plan. Users had to sign up for a two-year Verizon contract at $70 per month — just over $100 in 2025 money — which likely priced most teens out of owning one. The sales figures reflected that, as Microsoft allegedly only sold 500 units and pulled the plug on Kin after just 48 days.

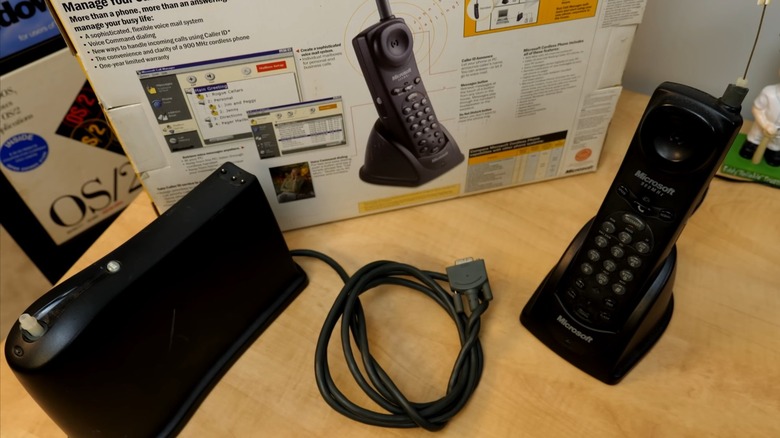

Microsoft Cordless Phone System

Lumia and Kin weren't Microsoft's only failed attempts to establish itself in telecommunications. Over a decade before the company's first Lumia smartphone, Microsoft tried its hand at a home and office telephone called the Microsoft Cordless Phone System.

Microsoft's Cordless Phone System wasn't just a standard wireless phone with a logo slapped on it, though. Microsoft brought some of its tech prowess to bear in designing the phone, pairing a commonplace 900-MHz analog wireless connection with PC connectivity. The phone's base station connected to a PC — Windows 95 and Pentium 90 or higher required — via serial and allowed owners to use Microsoft's Call Manager software and access some fancy features.

These included caller ID features such as personalized greetings, blocking, and caller announcements. The phone also had voice command support, and owners could, for example, tell the phone to call people, return calls, or delete voice messages. Sadly, the Cordless Phone System flopped, although it's hard to say whether it was due to the high $199.95 retail price — better-performing 2.4-GHz digital systems were already available at a similar price — or its extremely niche appeal for the time.

Microsoft SPOT

Ah, the smartwatch. They're not perfect, but smartwatches are a common sight on modern-day wrists, with more than 20% of U.S. adults owning and using one according to data gathered by Market.us Scoop. Apple is the leading name in smartwatches, with its Apple Watch making up nearly a quarter of all smartphone shipments as of 2024, but it's Microsoft that the smartwatch arguably owes even more to, thanks to its Smart Personal Object Technology (SPOT).

Now, to be clear, Microsoft didn't make the smartwatches themselves. As with Google and its Wear OS ecosystem, Microsoft left the watch hardware to recognizable names such as Tissot and Suunto when it debuted SPOT in 2003, focusing instead on the data side of the equation. To do this, the corporation used FM radio to beam data to these standalone, SPOT-enabled smartwatches via a service called MSN Direct.

MSN Direct — which cost $60 a year — would send information such as notifications and news to the watches, which operated as purely standalone devices. They didn't need a phone or a computer to work, but that's precisely what some critics point to as SPOT's primary downfall: knowing you had a new message on MSN Messenger was fine, but the watches didn't let you do anything about it. Microsoft stopped selling smartwatches in 2008, and MSN Direct followed them into the Microsoft graveyard a few years later in 2011.

Microsoft/Timex Datalink 150S

As with its telecommunications efforts, the SPOT-powered smartwatches weren't Microsoft's first foray into wearable technology. For that, we have to go back to the mid-1990s and the Datalink 150S, a collaboration between it and watchmaker Timex.

The 150S, which debuted a year after the original Datalink, was a shrunk-down version of the original that featured Microsoft-developed software called WristApps. These apps included a stopwatch, countdown timer, and even a golf scorekeeper. Old hat now, perhaps, but we can imagine how impressive this would have been in 1995. The Datalink 150S could also store information such as phone numbers, appointments, lists, and addresses, all of which transferred to the watch via an application called Time Data Link.

Of course, as this was years before Bluetooth or USB connectivity became mainstream, the way you did this was quite trippy by modern standards. To transfer data, Time Data Link would flash a series of barcode-like lines on the computer screen, and owners would point their watch at the CRT to send the data from the PC to the watch. It definitely has an air of retro cool in 2024, although it sure makes us appreciate Bluetooth even more. We're not sure how long the Datalink was on the market, but magazine mentions of it seem to peter out after 1997, so it's likely safe to say that it was a short-lived offering.

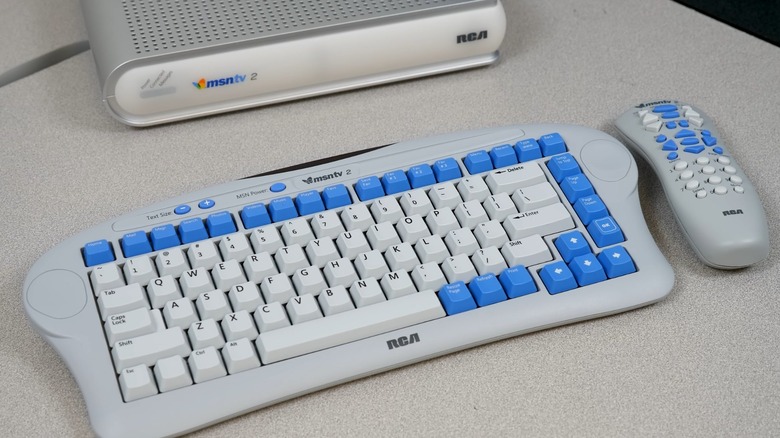

MSN TV

Microsoft and the TV in your living room go together thanks to the Xbox, the original version of which debuted back in 2001, but what if we told you that the Xbox wasn't Microsoft's first attempt at conquering your living room? Before the giant decided to wade into the console wars with the most powerful console of the sixth generation, there was MSN TV.

WebTV, as the service was known initially, was the brainchild of Steve Perlman. Perlman co-founded WebTV in 1995 to sell a set-top box that allowed users to access the internet via their TVs, with no computer required. Investors loved the concept, with the startup raising $65 million in funding — just under $130 million now — before the product's September 1996 launch. The device lived up to the hype, too, selling 50,000 units in its first year and counting tech icons such as Bill Gates and Steve Wozniak amongst its customers.

Barely a year after launching, Microsoft acquired WebTV for around $425 million — over $800 million in 2024 — in stock and cash. Unfortunately, WebTV's proprietary tech couldn't quite keep up with the rapidly developing internet, and rivals such as AOL TV began offering stiff competition. Microsoft renamed the service to MSN TV in 2001, trying to improve the subscriber base by giving the device away to MSN subscribers. It then completely ditched the original hardware with the MSN TV 2 in 2004, which trundled on for nearly another decade before Microsoft shut it down in 2013.