These Failed Formats Tried To Be The Next Audio CD, But Never Made It

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

In 1999, music consumption was shifting in a new direction. As home internet connections got faster, users discovered improvements that had been made in audio compression, making it trivial to download a song that sounded closer to CD quality at a time than everyone was used to hearing from smaller files. Though other similar formats, like Advanced Audio Coding (AAC), Windows Media Audio (WMA), and Ogg Vorbis would proliferate in time, the dominant format was MPEG-1 Audio Layer III, or MP3, for short. These formats all used lossy compression, with psychoacoustic modeling discarding the "least necessary" sounds to reduce file size. With increased broadband access, peer-to-peer file-sharing platforms like Napster became popular ways to exchange MP3s, all while the record labels fell behind the times.

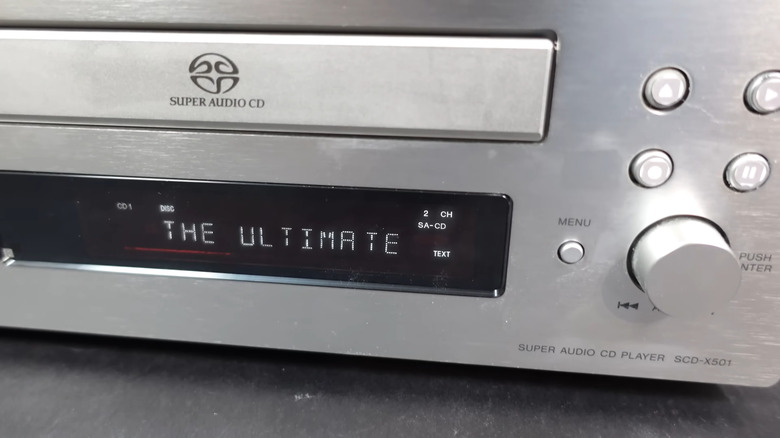

All of this is to say that, at the time, it was pretty clear that the mood was shifting to convenience over sound quality. On the average computer speakers and the cheap headphones that most people had, MP3s sounded great. Good sound had been heavily deemphasized to the consumer. Yet, in 1999, two separate physical media formats launched, attempting to preserve physical media by targeting users who wanted sound quality that was better than CD could deliver. These formats were the DVD Forum's DVD Audio and Sony's Super Audio CD, or SACD for short, which were vessels for high-resolution and multichannel digital audio. To the masses, they predictably bombed; let's look at their history to understand why.

What are the origins of DVD Audio and SACD?

The idea that CD audio was inherently flawed and could be better goes back to roughly the mid-1990s. In 1993, MTV's "Week in Rock" aired a segment about how some musicians and pundits were arguing that the CD standard of 16-bit (number of bits per sample), 44.1 kHz (number of samples per second) digital audio wasn't enough. with analog formats like vinyl records capturing the missing nuances. "Perhaps the best way to make digital sound more like a continuous thing is to have more samples per second," concludes the narration of the piece. "The technology exists to do that now, but until such a system can be made compatible with current CDs, we're unlikely to get it."

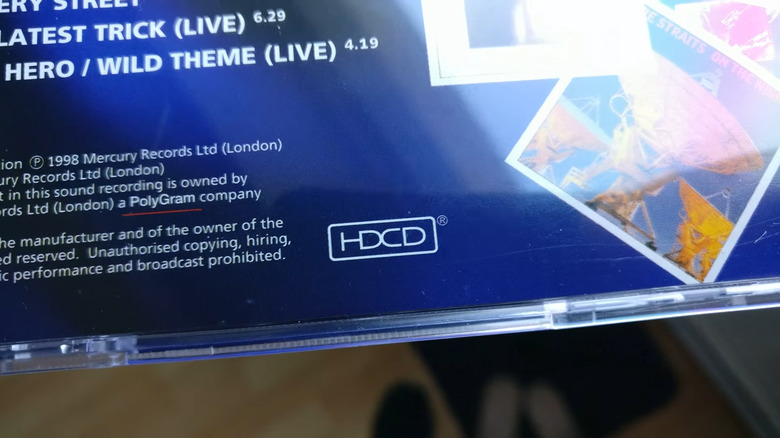

Around the same time, word of the upcoming HDCD format, with a 20-bit word length and higher sample rates, made it into publications like Billboard and the New York Times; it hit the market in 1995. Though numerous titles released on CD in the next few years had HDCD enhancements — hitting the 1,000 mark by 1999 — the hardware needed to hear the hi-res music never achieved mainstream popularity, even after decoder prices nosedived.

By mid-1999, reports surfaced of both the DVD Forum and a Sony/Philips partnership having plans for a hi-res audio format using the newer, higher-capacity DVDs, but it wasn't clear if those projects were separate or overlapping. Months later, in March 1998, it was established that these would be separate, competing formats.

What were the differences between the formats?

The full details of the SACD format were announced in September 1997, with Sony and Phillips timing the announcement to coincide with the Audio Engineering Society (AES) Convention. Sony promised high-density, dual-layer discs capable of holding high-resolution stereo and surround sound mixes of a given album, plus a CD layer that was compatible with conventional CD players. SACD used Sony's Direct Stream Digital (DSD) codec, which was touted as state-of-the-art. "It's good," legendary mastering engineer Bob Ludwig told Billboard. "It's superior to some of the 24-bit, 96-kilohertz audio that I've heard," he added, referring to hi-res implementations of the PCM audio used by CDs.

It wasn't until March 1998 that the DVD Audio spec was settled on: PCM audio with 16, 20, or 24 bits per sample with sample rates ranging from 44.1 to 192 kHz. In time, the DVD Forum selected Meridian's lossless MLP codec for DVD Audio to reduce file size, as well. "With 96 kHz and 24 bits, you don't hear digital artifacts," David Chesky of audiophile label Chesky Records told Stereo Review. "At 44.1 kHz, there's hardness of timbres and lack of space."

Whatever the format, come AES 1998, legendary rocker Neil Young was ready for a hi-res future. "The artist should be able to have a palette to deal with, a way to make the decision of the quality vector of this music that you're going to hear for the next 20 years," he told Billboard.

How were DVD Audio and SACD positioned to the consumer?

Sony was adamant that there was no format war in the first place as the 1999 launch of SACD and DVD Audio inched closer. "Sony views DVD Audio as one feature of the DVD format, and we are one of the strongest supporters of the DVD format," Sony Corp. spokesman Daniel Lintz told Billboard. "We have no intention of starting a format war with DVD Audio, and we do not expect one to occur."

In other words, Sony was positioning SACD as the direct successor to CD and DVD Audio as a DVD Video offshoot for home theater enthusiasts, an idea that DVD Forum member Warner Music Group disputed. Either way, SACD was a premium audiophile product at launch, with Sony's first players retailing for $4,000 to $5,000, while DVD Audio players started at a more conventional new format price of $1,000.

Though Sony claimed that most people could hear the difference between CD and hi-res, not everyone was so bullish. In a May 1999 Financial Times story, Alice Rawsthorn noted that Sony had pushed failed formats like Betamax in the past where technical superiority wasn't enough to win a format war, with MP3 downloads, in particular, serving as the biggest threat to the new discs despite the fidelity difference. Stereo Review, meanwhile, correctly predicted that, in time, internet streaming would become the primary delivery system for digital music, including hi-res.

How were DVD Audio and SACD received?

A December 1999 New York Times article noted that the industry consensus was that adoption of one or both of the new audio disc formats would "take many years." The article doesn't get into the granularity of how many years would qualify as "many," though. Brinkley noticed "a notable leap forward in sound quality" on both formats, favoring SACD as less harsh and more real-sounding. However, he conceded that Sony provided him with a $16,000 stereo system for the review. To wit: In the September 1999 edition of his "The Common-Sense Audiophile" column in Fanfare, Al Fasoldt outright said that "most of the market will not care" about hi-res audio. After all, it's not like most people were buying proper stereo systems anymore.

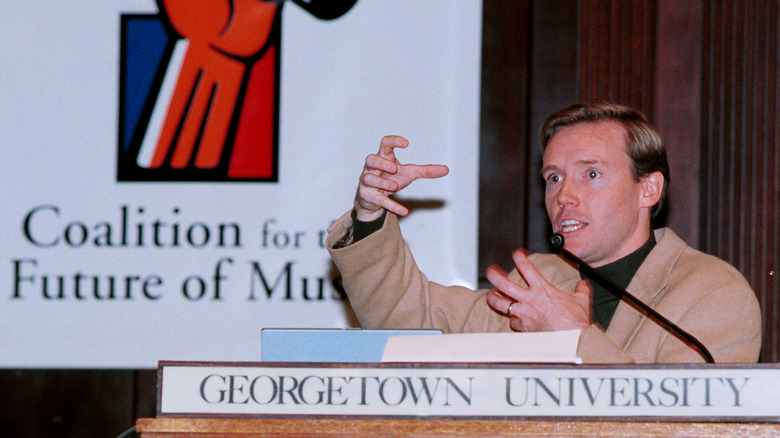

Even as early as 2000, it seemed like the writing was on the wall for the hi-res discs. In March, headlining the International Recording Media Association conference over a panel on SACD and DVD Audio was a keynote speech from MP3.com founder Michael Robertson. Wired, meanwhile, published an article in June that was very skeptical of DVD Audio's chances. It didn't seem like the industry realized that most people were happy enough with MP3 that the superior fidelity of the hi-res formats would be seen as extraneous. By 2007, The Guardian decreed that DVD Audio was extinct and demand for SACD was minimal, with the convenience of MP3 and similar formats winning out over high fidelity.

Why did SACD and DVD Audio fail?

Even if you set aside how the music industry was trending towards convenience over fidelity when SACD and DVD Audio launched, the new formats had plenty of other hurdles that made mass adoption unlikely. For starters, they were confusing. While DVD picked up steam as a mass market home video format quickly, most garden variety players didn't support either of the new audio formats, necessitating the purchase of expensive new hardware. Perhaps even more confusingly, most DVD Audio discs — but certainly not all — contained a DVD Video layer with lossy Dolby Digital or DTS audio that would play in conventional DVD players, but this was not clearly explained to consumers.

Even if the multichannel aspect appealed to you, it was likely that your existing multichannel source was a regular DVD player for video discs, and there wasn't necessarily enough multichannel music to push purchases of new hardware. Cheap home-theater-in-a-box systems strictly played DVD Video, too. When Sony attempted to drive Blu-ray adoption via the PlayStation 3 gaming console, which worked as planned, it initially bundled in SACD playback functionality as well for similar reasons, but that was dropped before long when Sony had to cut features to get the console's price down. That discs in the hi-res formats were never particularly plentiful, coming out at a slow pace, just compounded all of the other factors that helped stifle mass adoption of DVD Audio or SACD.

Wait...you never said that SACD was discontinued

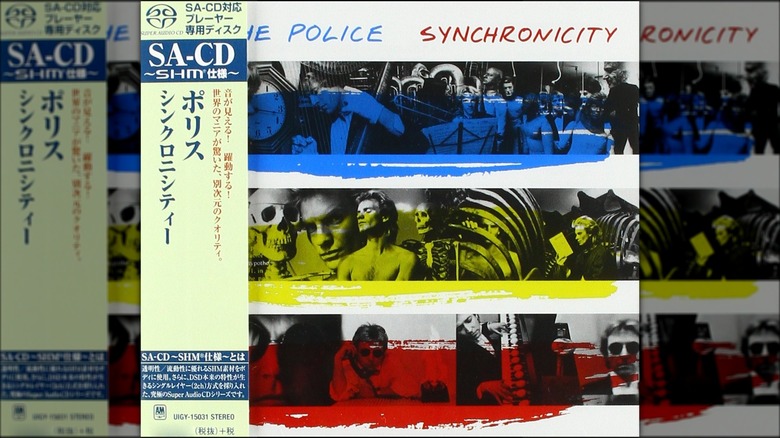

Despite DVD Audio being dead since roughly 2007 and streaming becoming the dominant format for hi-res digital music, SACD never actually died off. New playback hardware is still available, and though you're unlikely to see much in the way of new pop or rock titles on the format, plenty of classical music still comes out on SACD. Specialty labels such as Mobile Fidelity Sound Labs, Analogue Productions, and Intervention Records keep reissues of older pop/rock titles in the pipeline, as well. Though it's not every title, a significant number of the titles released by those labels on vinyl also get hybrid SACD releases. If you're willing to look into import titles as well, there is also the SHM series in Japan, short for Super High Material, which is exactly what it sounds like, though it tends not to be hybrid SACDs or include a traditional CD layer.

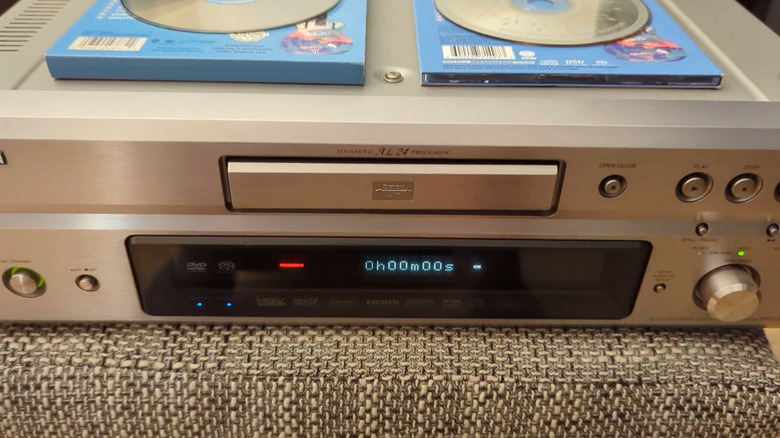

If you're at all interested in SACDs, the playback hardware is a lot more accessible and inexpensive than you might think. Sony still includes SACD playback functionality in some Blu-ray players, including the BDP-S6700, which sells for $120 at Walmart. Strangely, Sony does not advertise this fact at all in the official feature list; the device manual is the only "official" source for this information. Outside of select Sony Blu-ray players, the market is centered around high-end players from the likes of Denon, Marantz, Yahama, McIntosh, Technics, and Luxman, selling across the continuum of the four-figure price range.