10 Seemingly Modern Gadgets That Have Been Around Way Longer Than You'd Think

Here's a fun fact: the fax machine is much older than you may realize. Contrary to popular belief, it wasn't invented at some point in the mid-20th-century. More like the mid-19th-century. That's right — people have been able to send faxes since at least 1843, before even the American Civil War. A lot of seemingly modern technologies go back further than you might think. Some, like the refrigerator, were first conceived only a couple hundred years ago. Some a couple thousand. To give an example, Sumerians had a primitive form of air-conditioning circa 6,000 BCE.

Case in point, many of the technologies you take for granted as modern devices from the past few decades have a more historical origin than first meets the eye. In that spirit, the below devices and gadgets are commonly mistaken as modern day inventions, but actually go back hundreds or, in some cases, thousands, of years.

Turn-by-turn car navigation

One tech gadget that can make your old car feel new is a receiver with a built-in GPS and turn-by-turn directions. You might assume this modern convenience is only about 20 years old, considering that GPS technology only became available to the public in its full form in 2000. However, pre-GPS automobile navigation first made headway in 1909.

Back then, roads were a shadow of what they are now. There were no highways, and most were not paved. Directions at the time were very much of the "turn left at Farmer Joe's, then walk 50 paces north at the oak tree" variety. The automobile changed travel entirely, and included fascinating early navigation devices like Jones Live Map — invented by the man who thought up the speedometer.

The Jones Live Map was a spinning disc with place names, road conditions, and directions for a specific route printed along its turning edge. You hooked it up to your odometer, and as you drove, the disc spun in relation to distance traveled, giving a very rough idea of where you were and where you should go. You had to replace the disc at intervals, such as when it completed a circuit. It was imprecise, but it got the job done. Other devices, like Chadwick's Road Guide, featured primitive turn alerts that even worked at night. Later, the Baldwin Auto Guide further built upon this idea by featuring a hand-cranked map with an electric light. Many other devices tried to solve this car navigation problem, proving Google Maps is built on the shoulders of giants.

[Featured image by Dwxn via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CCA]

Computers

Computers go pretty far back depending on how you define "computer." You might think of early IBM devices, or Turing's Colossus that the Brits used to defeat the Nazis' enigma. Charles Babbage's Difference Engine in 1832 was an even earlier example. But the one we want to home in on is at least 2,000 years old, known as the Antikythera Mechanism. It was found in one of the most fascinating shipwrecks off the Greek island of Antikythera in 1901.

This clockwork box of metal gears befuddled scientists, given how modern it appears and how little of the actual device remained. For decades, no one knew what it was designed to do. A 2021 study in Scientific Reports, via University College London, digitally rebuilt the device and posited that it was used to calculate the movement of celestial bodies. Namely, the sun, the moon, the planets, and the stars, perhaps also with the capability to track eclipses and seasons. You'd wind the gears to figure out where these bodies would be at certain times of the year, in theory, making it an analog computer.

It would appear the Antikythera Mechanism worked — at least with the limited astronomical reckoning of ancient times — but it remains to be seen how useful or widespread it was; the mechanism is the only one of its kind to be discovered. Regardless, it's things like this that prove earlier societies were likely significantly more technologically advanced than originally thought.

Electronic synthesizers

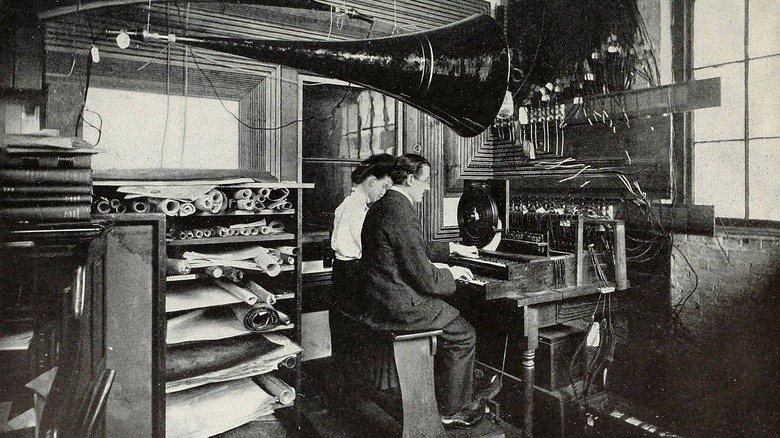

Electric instruments only started to appear in the early 20th century, such as the theremin — which, by the way, you can build with a Raspberry Pi. Proper electronic synthesizers as we know them today started as 1950s technology. The true granddaddy of electric instruments, however, was the Telharmonium (also called the Dynamophon), and it made its to mark on the historical record in 1895. Thaddeus Cahill came up with the name (a portmanteau of "telegraphic" and "harmony") because he dreamed of a world where people could experience music long-distance through the telephone. Keep in mind, radio wasn't patented until 1897.

Cahill's initial idea was to create a device that could produce the sounds of distinct instruments and layer them together into a composition. He was not the first person with this dream, nor the first to transmit music over long distances, but the Telharmonium sticks out regardless. The device was huge. According to Google Arts and Culture, the second version built in 1902 weighed 200 tons, had eight metal pipes, 144 alternators, 2,000 switches, 672 keys, and 336 sliders — and it took 15,000 watts to run, which wasn't small potatoes for the early electric grid.

The Telharmonium is also, arguably, the first to supply 24/7 music streaming. Cahill charged $5 a month to listen to it over the telephone. Alas, it didn't last long. A number of issues — service disruptions, tuning troubles, and the logistics of keeping musicians on the clock 24/7 — led to its downfall. Still, this was an incredible device for the time, one that Mark Twain quipped made him want to "postpone [his] death" to avoid missing out on more creative inventions like it.

[Featured image by Unknown author via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CCA]

Drones

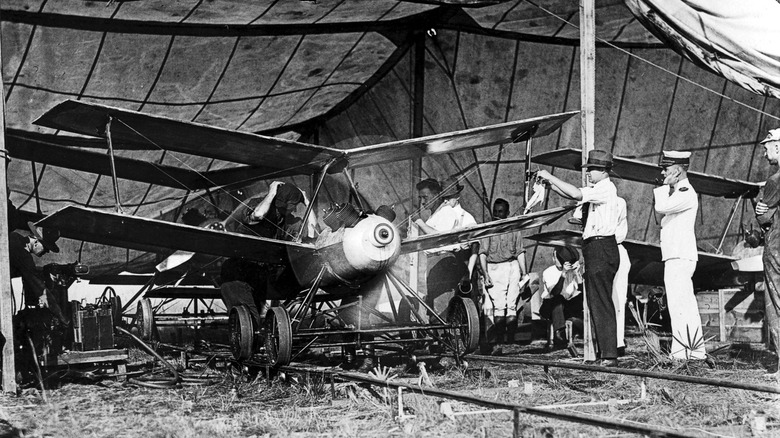

The US military was operating the GNAT 750 and the infamous MQ-1 Predator in the early '90s, and the IDF in Israel had the Tadiran Mastiff as early as 1973. It's only in the past decade or two that drones have become affordable and widespread for the average consumer, like this $200 DJI Neo. The concept of unmanned vehicles goes back hundreds of years to when Frenchmen were dropping bombs from hot air balloons, but as for completely autonomous drones as we view them today, the Kettering Aerial Torpedo Bug (or simply Kettering Bug) is the earliest candidate. It first appeared circa 1917 in the heat of World War I.

Now, the Kettering Bug obviously did not have a remote control or camera feed, but it was autonomous in the barest sense. According to the USAF National Museum, the Bug's "pre-set pneumatic and electrical controls stabilized and guided it toward a target." Once in range, the wings would pop off and the Bug would convert into a torpedo packing 180 pounds of explosives. From then on all it needed was gravity to finish the job.

Though a brilliant idea for the time, the Bug never deployed over the trenches of Western Europe. Postwar, the U.S. military still envisioned it on the front lines, but development came to a standstill in the 1920s. In any case, WW1 was already the debut of horrific inventions like the machine gun and mustard gas, so maybe it's a good thing that it didn't birth drone warfare as well.

[Featured image by US Army via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CCA]

Voice-identification security devices

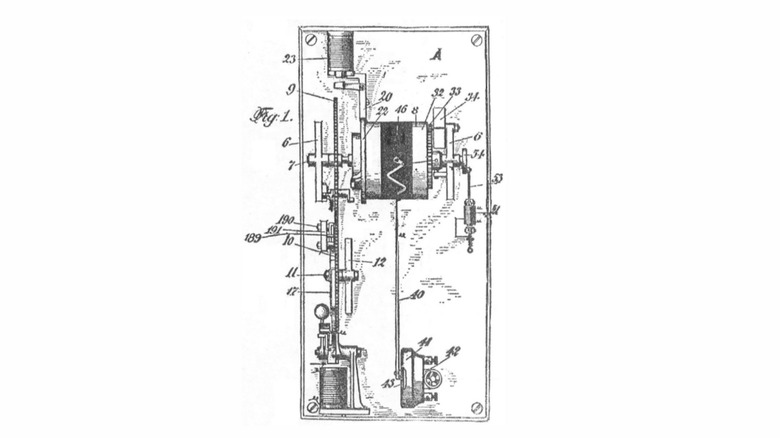

Voice-identification technology has been a staple of sci-fi and fiction for decades. It seems foolproof; your voice is as unique as your fingerprint, and you can't exactly lift someone's voice like you might a fingerprint. Now the feature is no longer cutting edge, with banks using voice activation to verify a person's identity, and hackers easily replicating your voice with AI. All of that aside, voice identification seems like the most modern of modern technologies on this list; a digital, algorithm-based thing that can't be much older than a couple of decades. But the first instance of voice identification goes back to at least 1908 with the Countersign Phonograph Lock.

According to The Sound Box, this locking mechanism was intended to be used with a safe. To open it, you had to say the "countersign" — like Edna Mode speaking her name to unlock her lab in "The Incredibles." You spoke it into a mouthpiece and waited for the lock to compare your voice to a master inscribed on a cylinder. If the stylus didn't match up the grooves of the sound wave exactly, then the safe didn't open.

Full disclosure: the Countersign Phonograph Lock was only a patent that never got approval, nor are there any records of it being tested. Its inventor, Elliot Keen, went on to file all sorts of patents for things like shooting targets and gyroscope compasses. It's impossible to say if his voice-identification lock worked, but regardless, it shows how far back the idea of using voice as a fingerprint goes.

Video game consoles

When you think of old video games, you think of valuable retro consoles like the NES and the Atari. Don't get your hopes up — there wasn't was some forgotten video game system available in Victorian times, but there was one as early as 1947.

It was dubbed the "Cathode Ray Tube Amusement Device" by creator Thomas T. Goldsmith Jr. The device included an old CRT screen that mimicked a radar display, and the object of the game was to shoot down airplanes via the control knobs. The airplanes had to be attached to the screen by hand, as the device was a bit too early on the scene to have moving, enemy AI planes. The aircraft would even "explode" when struck, quite impressive for a contraption of the time period.

As you can probably guess, this was a huge setup with a bulky screen and a closet-sized computer. You couldn't buy one; Goldsmith created it as a proof of concept, and it never entered production. Later developments in video games, such as "Spacewar!" In 1962, quickly overshadowed the Amusement Device and relegated it to the annals of history. Whatever the case, it's fascinating to think that there was a playable video game just a few years after World War II.

Flame throwers

Flame throwers appeared on the military scene shortly before World War I, then again in World War II with the M2 flamethrower. Flame throwers became the terror of Vietnam where U.S. soldiers deployed them with napalm to burn through the thick vegetation. But the earliest recorded flame thrower was built over a thousand years ago by the Byzantine Empire during the 7th century. Callinicus of Heliopolis invented Greek fire, which was effectively a Middle Age napalm; it clung to virtually any surface, burned ferociously, and seemed to burn even more so when doused with water. Perfect for naval warfare and, well, a flame thrower. So why not both?

The Byzantines did just that. They put flamethrowers on the front of their ships and then sprayed Greek fire all over the enemy's very wooden vessels. You can probably guess what happened next. There even existed a handheld "cheirosiphon" for soldiers to carry with them on the battlefield. Needless to say, Greek fire tilted the balance in favor of whoever had it. Byzantine emperors, understandably, kept its recipe tightly under wraps.

No one knows for sure how it was made, but it does closely resemble napalm. Maybe that's good news, since it's hard to imagine a substance doing any good for the world if re-discovered. There could very well be a bit of historical exaggeration going on here too, but regardless, Byzantine ship-mounted flame throwers with Greek fire remain a fascinating, terrifying chapter in history.

[Featured image by Unknown author via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CCA]

E-readers

Seemingly the most obvious precursor to the e-reader is the PDA, one of those weird '90s gadgets that was quickly forgotten in the wake of smartphones. But let's not be too hasty, because someone else beat Silicon Valley to it: a Spanish schoolteacher by the name of Ángela Ruiz Robles in 1948. According to The New York Times, her Enciclopedia Mecanica (Mechanical Encyclopedia) was the size of a book and featured a series of horizontal spools that would scroll text, drawings, or anything in between. It operated on battery power and included a lightbulb for nighttime reading. Her reason for inventing it? To lighten the load on her students.

Despite her noble intentions, Robles did not, unfortunately, find much success. None were willing to invest in the Encyclopedia and it never saw a widespread use. One could say it was too far ahead of its time; bound paper is more intuitive and never runs out of battery. It wasn't until slim, modern e-readers like the Amazon Kindle and Nook that reading anything but a physical book became an enticing proposition. In any case, Robles dreamed up an e-reader-like device long before the technology was in her favor — and long before Jeff Bezos was even born.

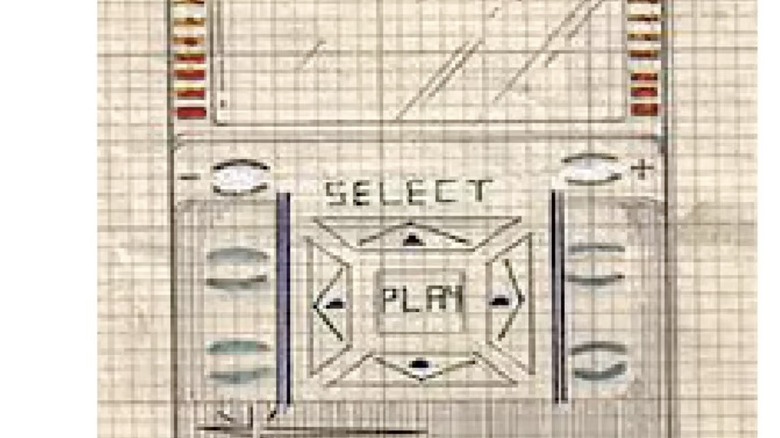

Portable digital music players

The iPod was the king of portable music players, so good that a used iPod is still worth it today. But neither Apple nor America is responsible for creating this genre of device. That honor goes to the IXI System, the brainchild of Englishmen Kane Kramer and James Campbell in 1979. The device was very reminiscent of the iPod we are familiar with today: roughly the size of a cigarette pack with a screen and four-way buttons (via Wired). Given the technological limitations of the time, it boasted 3 minutes of music playback.

And that's just the beginning. The partners envisioned a telephone-based distribution network where users could drop by their local music store to load digital music onto their devices. They even concocted a system of "DRM" to prevent users from illegally bootlegging songs.

The IXI System was, like the Mechanical Encyclopedia, too far ahead of its time. In a depressing instance of irony, it's possible Apple waited for the patent to expire before copying the IXI System when making the iPod in 2001. The only reason people suspect this — other than the fact that the iPod leaned hard into that particular design — is because Apple brought it up in court while suing someone else for infringing on its iPod patent later on.

Wearable devices

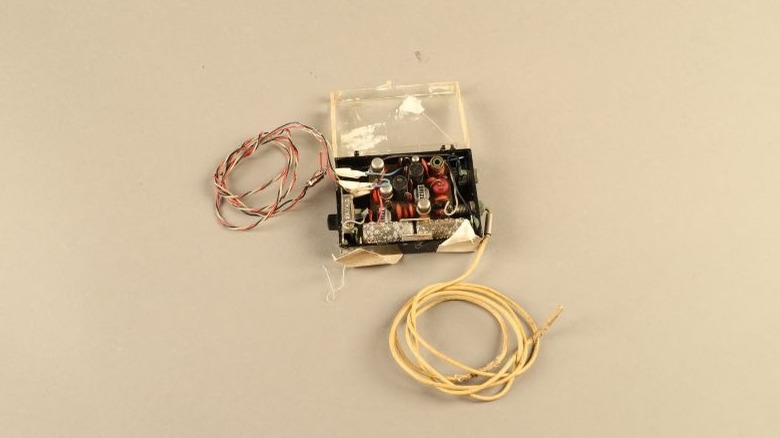

Leonardo da Vinci once sketched out a rudimentary pedometer that worked by tracking the swinging of your arms. As for electronic wearables, like the Samsung Galaxy Watch or the Apple Watch, even they has a history more distant than the Fitbits of the late '00s. In 1961, Edward Thorp and Claude Shannon of MIT worked to create a "wearable" device that could thwart the casino.

Aptly named the "wearable roulette computer," all the device was doing was using mathematics to time the spinning of a roulette wheel, according to Engadget. You wore it around your waist, using the tap of your foot to control it. An earpiece produced tones that would indicate when to place a bet. Thorp had a particular interest in mathematics and games of chance; he had previously devised a method for counting blackjack and winning.

The wearable computer wasn't a precise science, but it gave players a 44% edge — a big deal, considering you might have only 1-in-38 odds playing roulette. During early at-home testing, Thorp and Claude won $8,000 of make-believe money, so it was time to test it in a real casino. They were successful. Money started to quite literally pile up, with the only damper on the fun being broken wires and the fear of getting caught. This certainly wasn't a device meant to make anyone a millionaire by cheating in the big stakes games (like that scene from "Casino") but it was a fascinating little proof of concept.