7 Discontinued Home Video Formats That Were Commercial Failures

Physical media is dead. Well, at least that's the saying. Tens of millions of units of physical music titles still move each year, with even CDs selling respectably despite more vinyl records being sold. And even though physical video sales have slowed, the fourth quarter of 2023 showed positive signs of growth for Ultra HD Blu-ray discs. There's still a distinct class of customer willing to pay for higher fidelity video and audio than streaming is capable of achieving. Still, we're now in a world where "all you can eat" streaming services dominate and offer a level of quality that's good enough for most people. But there will always be a place for physical media, whether it's due to the superior fidelity currently offered via the higher bitrates available on Blu-ray discs, a greater freedom of viewing for those without reliable broadband service, or access to titles not licensed for streaming.

On the video side, the last four most viable formats to date — VHS, DVD, Blu-ray, and Ultra HD Blu-ray — all had to outlast a bunch of other formats that stood in their way. Some were direct competitors: VHS toppled Betamax in the videotape format war, while Blu-ray did the same in outlasting HD-DVD. Others tried to satisfy specific niche audiences, like Laserdisc aiming at early home theater enthusiasts or UMD for entertainment on-the-go. Others still came to market with no clear plan and got slaughtered. Let's look at which video formats died brutal deaths and why.

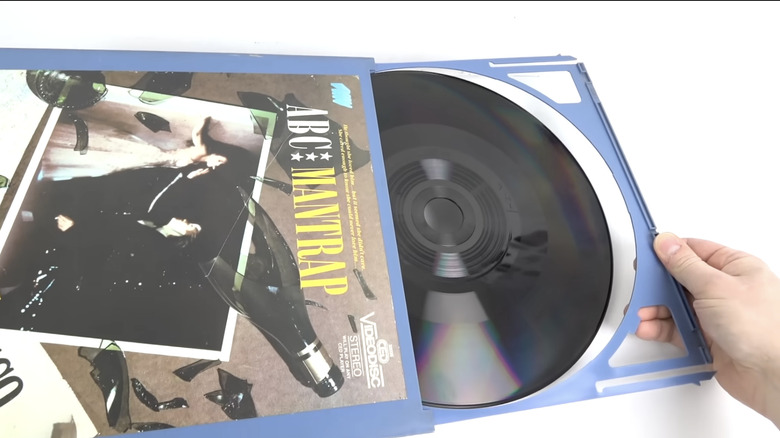

Laserdisc

One format that helped innovate some of the features that would help popularize DVD but never emerged beyond niche status was Laserdisc. A joint creation of Pioneer, Philips, and movie studio MCA, Laserdisc utilized 12-inch discs, the same size as long-playing vinyl records, but they were optical discs like CDs and DVDs, read by lasers. Unlike CD and DVD, though, Laserdisc was launched in 1978 as an all-analog format, with the video always being analog throughout its lifespan even after being joined by digital audio. The big benefit of the addition of digital audio was the ability to carry discrete surround soundtracks using Dolby Digital AC3 or DTS encoding. That wasn't the only proto-DVD feature offered up, though: It also supported chapter skipping and the presence of multiple audio tracks, with features like commentary tracks first emerging on the format.

Though Laserdisc found an audience with discerning videophiles and home theater enthusiasts, it never really escaped that niche for various reasons. Players and movies were more expensive than VHS tapes, for starters. From an ease of use and overall frustration perspective, the biggest problem may have been that each side of a disc could only hold 64 minutes of video (under 30 minutes on earlier discs), requiring a disc flip for most movies and an additional disc for longer titles. To make matters worse, poor production and assembly caused discs to fail while the format was still active. Once DVD hit in the late 1990s, the writing was on the wall for Laserdisc.

RCA Selectavision Videodisc

Laserdisc wasn't the only analog videodisc format to come of age during the rise of VHS videotapes, and it certainly wasn't the biggest flop. That distinction would go to RCA's CED Videodisc format, also known as Selectavision, which was effectively an attempt to adapt vinyl records into the video realm. Even before it hit retail stores, it was a bit of an oddity, as Laserdisc had beaten it to market by a few years. If it had an advantage over Laserdisc, it was the lower cost of discs, with Selectavision videodiscs retailing for $15 while Laserdiscs sold for multiples of that amount. Otherwise? It was a bizarre, kludgy format that probably never would have made it to market if not for RCA needing to at least try to recoup research and development costs.

As you might be able to imagine, mastering video and audio onto the already finicky vinyl record format was a bit of a challenge. Grooves had to be pushed closer together, increasing margin for error, and a protective caddy was used to load the discs, which were coated with a lubricant, into players. Functionally, there were no real obvious benefits over the much easier-to-store VHS tapes, with the only clear factor in Selectavision's favor being price. VHS prices lowered quickly enough for that difference to fade, though. Over the course of three years, RCA sold just 550,000 Selectavision players, leading to the company discontinuing the ill-conceived format on April 4, 1984.

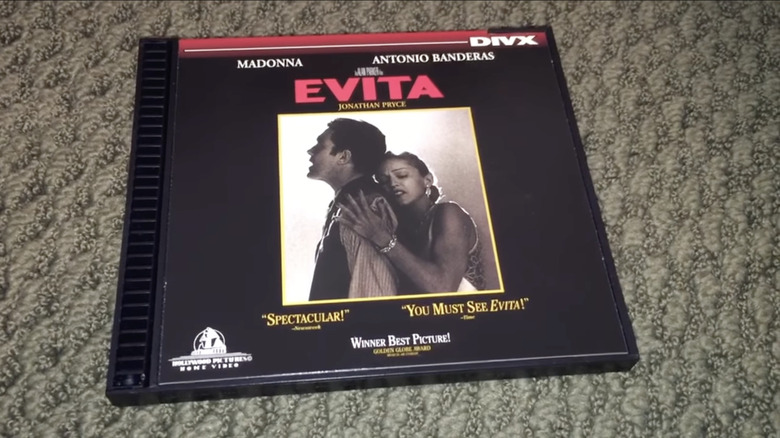

DIVX and Flexplay

During the DVD boom, there were two attempts at modifying the format to allow for customers to rent movies without returning them and also extend rental capabilities outside of the stranglehold that Blockbuster Video, and later, Netflix, had on the market. One of these was 1998's DIVX (not to be confused with the MPEG-4 video codec implementation of the same name), a format backed by electronics store chain Circuit City that required specialized hardware, and the other was Flexplay, a self-destructing DVD that had a 48-hour lifespan once it was opened and exposed to oxygen.

DIVX, a partnership between Circuit City and a law firm, at least predated the rise of Netflix, but was hamstrung by the need for specialized hardware. For $5, you could get a disc that became useless 48 hours after you started playing it...unless you bought or re-rented it using your internet-connected player. With DIVX discs lacking the extra features of retail DVDs and there being no clear reason to seek out a DIVX player over a regular DVD player, the format was killed off a year after its launch. Circuit City lost $337 million on the project after taxes.

Flexplay, launched in 2003, was similarly pointless. It worked in regular DVD players, but amidst complaints about environmental impact, the company behind it offered free return labels for recycling. This was years after DIVX, though, with Netflix by mail and kiosk-based Redbox thriving, so it quickly became obvious this was a pointless endeavor.

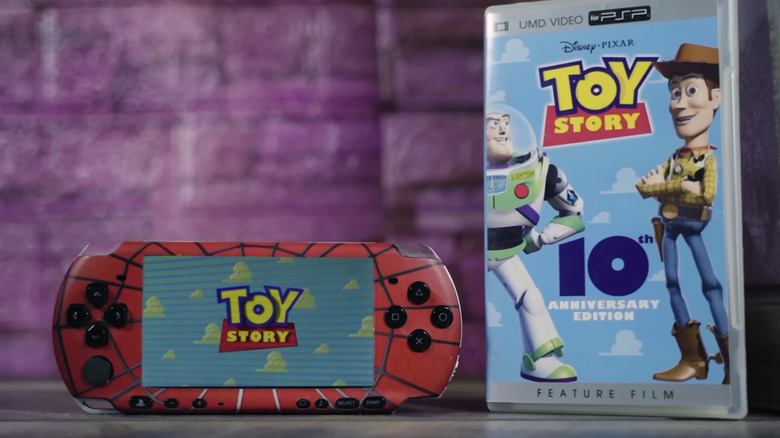

UMD

Today, portable/mobile video viewing is ubiquitous. Everyone has a smartphone, and younger people, in particular, are big on watching lots of video on their handsets. In the early to mid-2000s, though, it was a much different world. The first iPod with video playback functionality didn't hit the market until October 2005, and even then, it had a smaller screen than what we'd become used to once the smartphone boom hit. Earlier in 2005, though, a different portable device with a secondary focus on video playback made its way to retail stores: Sony's original PlayStation Portable (PSP for short) handheld console. From the jump, one of the selling points was that, besides the PSP being a high-end portable console, it would also have movies released for it on the same proprietary Universal Media Disc (UMD) format that housed the system's games.

In the early weeks of the console's existence, UMD movies did surprisingly well, with "Resident Evil 2" and "House of Flying Daggers" each topping 100,000 units sold. By the time the console had been on the market for a year, though, the sales didn't sustain. Variety reported in February 2006 that outside of "comedies that appeal to the core young male gamer demo," the major studios were significantly cutting back on their PSP releases, while Walmart soon reduced the shelf space allotted to them. Though new games continued to be released on UMD all the way until 2014, UMD movie production slowed significantly until it stopped in 2011.

HD-DVD

Sometimes, a home video format doesn't die because it came to market with a lack of demand for its particular feature set. Legitimate demand could be there for a new format, only for competing standards to emerge in a format war, where only one winner is left standing. That's what happened to HD-DVD, which came out on the losing end of a battle with Blu-ray. Both were five-inch optical discs that were engineered to hold a lot more data than DVDs so as to better accommodate high-definition content, with Sony and Philips behind Blu-ray and Toshiba behind HD-DVD.

From the jump, though, Blu-ray had a clear advantage that set the stage for its eventual victory: While HD-DVD could hold 15GB on a single-layer disc and 30GB on a dual-layer disc, Blu-ray discs held significantly more, 25GB on a single-layer disc and 25GB for dual-layer. This allowed Blu-ray discs to support higher bitrates for better picture quality or, alternatively, holding more hours of video. Blu-ray also had other advantages, like mandatory protective coating on the discs, and, eventually, broader support from the movie studios. The PlayStation 3 being one of the best Blu-ray players on the market while selling over 87 million units was also a significant boost for that format's adoption. The main points in HD-DVD's favor were the name, easier conversion of DVD pressing plants, and wider adult industry adoption, but that wasn't enough. Toshiba tapped out in 2008, just a few years into the battle.

Betamax

Sometimes, a format war can be a lot more of a marathon than a sprint. That's definitely the case when it comes to the home videotape format war that VHS won over Betamax, one of many discontinued Sony media formats, which was a real war for roughly a decade, from 1977 to Sony starting to make VHS hardware in 1988. That timeframe is complicated, though, by studios releasing Betamax movies until 1996, plus Sony's decision to continue manufacturing the hardware and blank tapes through 2002 and 2016, respectively.

It's often said that Betamax had better picture quality, but that quickly fell by the wayside thanks to VHS's longer recording time. (VHS also caught up to Betamax's advances in hi-fi sound and visual fast-forward/rewind as the war waged on.) The quality difference was most visible in Betamax's fastest recording speed, Beta I, but Beta I was largely phased out by 1979 because of the limited recording time. The most common tape lengths, L-500 and L-750 (named for the number of feet of tape in each cassette), could record 60 and 90 minutes, respectively, with the time doubled in Beta II and tripled in Beta III. The most common blank VHS tape, though, was the T-120 with 2 hours in SP mode, which doubled in LP and tripled in SLP/EP. T-160 tapes, holding up to eight hours, were also common. The gulf for home recording was too huge for a fidelity difference to counter, so VHS dominated in the 1990s.