13 Of The Weirdest Gadgets Sold In The 1990s

Ah, the '90s. The birthplace of "Friends" and the wailing screech of dial-up Internet. The music was pretty meh and fashion was quite forgettable, but it's a decade full of nostalgia for millennials. Especially when talking about the gadgets. Sure, the '80s had some awesome retro gear that has lingered forever in public consciousness, like Gameboys and Walkman cassette players, but the '90s had its own share. Think the Nintendo 64 and Tamagotchi. It also had some stuff that was downright weird — the nightmare that was the Furby was born at this time, after all.

The Furby was memorable, but it was far from the only goofy tech item you could purchase at the end of the 20th century. People were coming down off the high of the '80s, soon to be carried into the future by smartphones. This was a transitional era, so a lot of trial and error gave us some of the tech industry's most bizarre takes on what the future should look like. Today we're looking at 13 of the weirdest gadgets sold during the 1990s.

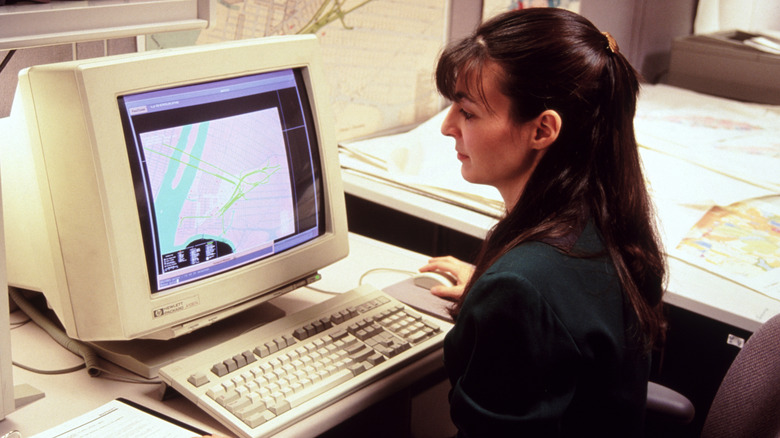

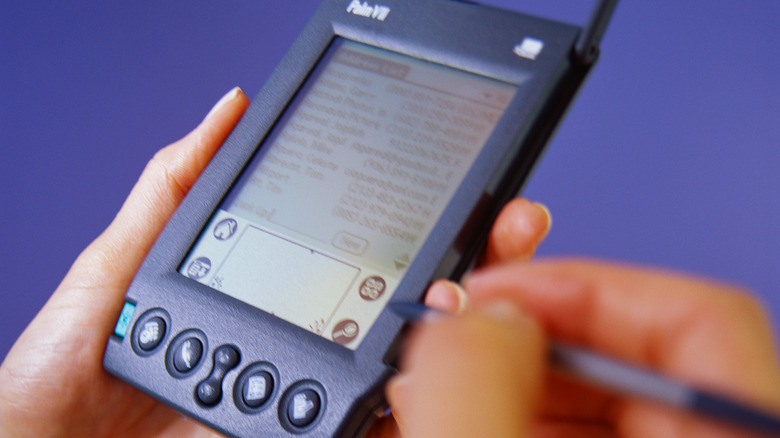

PDAs

Long before the iPhone took the world by storm, another device promised to be the end-all be-all item everyone would be carrying — the personal digital assistant, or PDA (also sometimes known as a Palm Pilot).

Ironically, it was Apple that created this category of device with the Newton MessagePad in 1993, which was the blueprint for all PDA's to come. The Newton MessagePad featured a black-and-white screen, stylus, and productivity-oriented software like calendars, word processors, contact information, and more. It even let you read e-books before the Kindle was a twinkle in Bezos's eye. Rather than use buttons or touch keyboard, PDAs had you write things out letter-by-letter using the stylus. Some PDAs even ran Windows — albeit, a heavily limited version.

Palm Pilots were made cool and simultaneously hamstrung by the technology of the time. Early versions had no Internet connectivity, so you had to wire it up to your computer or use an IR port until later Wi-Fi and cell support came around. They were expensive — the Palm III cost $399 in 1998 — niche, and more status symbol than essential work tool. They morphed slowly into early Blackberry-like devices, those pre-smartphone business phones such as the Palm Treo 650, which had a full keyboard. You know what happens next: smartphones put PDAs in the ground, and their manufacturers either went bankrupt or became a shadow of themselves.

Pagers

An easy way to find out whether or not someone is Gen Z is to ask them if they know what a pager is. For those who don't, pagers (sometimes known as beepers) were an alternative to early cell phones, except they couldn't make or answer any calls. Instead, someone would page you by calling your pager's number. Your pager would beep in response and display either a phone number or a code. Then, you'd have to find the nearest phone (likely a payphone, another thing commonplace in the '90s) and dial the number on your pager's screen to receive a message from the operator, or get in contact the caller directly.

Pagers were a status symbol owned by 61 million people, and those people no doubt thought they looked cool getting beeped in front of all their friends. "Hey guys, excuse me, just gotta take this very important call."

The devices doubled as a rudimentary means of texting since you could send a numeric code that folks at the time had memorized. Drug dealers also loved them for reasons that are probably obvious, as The New York Times reported in 1998. But in retrospect, it definitely looks more silly than cool. Pagers are still in use today by doctors and emergency responders.

HitClips

The Sony Walkman is a fascinating icon of on-the-go music listening, an important predecessor to the iPod, the MP3 player, and many other portable music options. One such alternative was HitClips, a short-lived child's toy that appeared in 1999.

HitClips looked like a little Walkman, had only a play button, and came either with a speaker or an earphone. To use it, you inserted a small memory card containing a 60-second clip of a song from a popular artist of the time such as Britney Spears. That was it. Unless you had a ton of memory cards, you were stuck playing that 60 seconds on loop until you got bored — which was likely, because back then (when the Internet was relatively new and expensive) a kid might not have had anything better to do.

It was an interesting idea, certainly weird, but ultimately not highly successful since HitClips only lasted until 2003. HitClips Disc released that year, doubling song length to 120 seconds, but was then discontinued in 2004. Apple's transformative iPod arrived in 2001, so it's no wonder why HitClips didn't survive the 2000s.

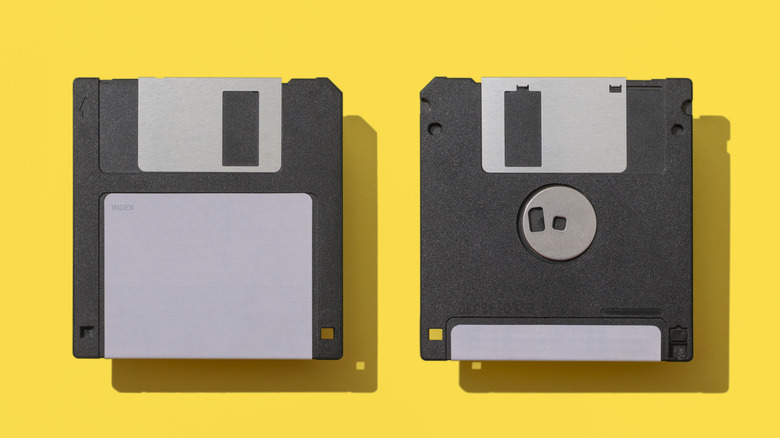

Floppy disks

Floppy disks were a bit of an oxymoron, since they were neither floppy nor disk-shaped — it possibly got that name because the original floppy disk had floppy packaging over a diskette storage medium. Regardless, this was the storage medium until CDs and the internet became a more convenient way to send files. They only held 1.44 MB worth of data, but when they first debuted in the '70s, they were a sea change. According to IBM, people essentially had to write their own programs by hand before then, so the introduction of floppies effectively gave birth to the software industry.

Floppies were part of the bedrock of critical systems like Boeing planes and the U.S. nuclear arsenal that reached their peak in the nineties. Even outside their essentiality in billion-dollar industries, they had sticking power with the average consumer. There was a time that you could buy a computer that had both a floppy drive and a CD drive combined. Obviously, floppies paled in comparison to their successor storage mediums, especially high-capacity, reusable USB thumb drives. It probably comes as no surprise that Apple was one of the first to phase them out with its iMac G3.

DVR

For kids that have grown up with streaming services, it probably comes as a surprise that back in the day – VCR aside – movies and shows played on a schedule. You had to be on time for when the episode of your favorite show played, and there was no pausing; the commercial break was when everyone ran to get a snack or go to the bathroom. Prior to on-demand streaming like Netflix, the stopgap was a DVR, or digital video recorder. The DVR was a box under your TV that you programmed to record your show to watch later, commercials and all.

TiVo was perhaps the most recognizable brand of DVRs back in the day, so much so that people used it as a verb. It went up for sale in 1999 for a whopping $499 (plus a subscription fee) and permitted only 14 hours of recording capacity. Another fun fact is it ran on Linux. Unless someone had a DVR, people in the '90s had to record their favorite shows with VCR, which obviously wasn't as convenient.

Of course, then came Netflix with its mail order DVDs and eventual on-demand streaming. TiVo is still around today and it makes its money licensing the technology it pioneered in the '90s. The DVR is weird by modern standards since we all watch what we want, when we want to but it was a huge cultural phenomenon at the time.

Car phones

Another status symbol that gives you a chuckle in retrospect is the car phone. Yes, a phone built-into your car. Prior to cell phones, this was the mobile phone, quite literally, appearing just after World War II in 1946. Cell phones have been around since the '80s, but it was far from ideal having to hold a brick-sized Motorola DynaTAC 8000X to your ear while driving — or really, doing anything at all.

Car phones made you feel like an ultra-wealthy Bond villain having a long distance chat during your morning commute or a road trip. They were typically mounted in the center console with a classic coiled-cable receiver and worked the same as they did at home. It's fascinating to imagine that something we view as very modern (taking a phone call while we drive) was something people were doing comfortably right up until turn of the century.

Of course, the historical record makes it pretty clear why car phones went the way of the dodo. Cell phones got smaller and cheaper in the '90s, eventually becoming smartphones that could pair to your car's receiver in the 2000s. Being the obnoxious rich guy taking calls in your car was soon about having a Bluetooth headset in your ear, not a car phone. You'd be hard-pressed to find even a used vehicle that has a car phone nowadays.

Apple Macintosh Portable

Before laptops had enough battery to be a viable on-the-go solution — and an affordable one at that — the '90s took a bunch of moonshots to figure out what portable computing was. Apple especially.

Before Apple had its amazing Apple Silicon MacBooks playing AAA games, it had the Macintosh Portable. This wasn't the classic taco design we know today, it was more of a desktop computer that you folded up and carried around like a briefcase. It weighed almost 16 pounds, was four inches thick, had a 9.8-inch black-and-white screen, cost $6,500, boasted flagship hardware specs for the time, and perhaps most surprisingly, packed a 10-hour battery.

While it was technically portable, the weight and size made it incredibly unwieldy. This wasn't exactly going to be something you'd be swinging around in your hand while walking down a crowded NYC street to a business meeting, especially knowing that it cost as much as a car. It had great reviews for the time, but for obvious financial reasons was not a commercial success.

Sony Glasstron

Living in the 2020s with the Meta Quest 3, it can be easy to forget the fits and starts that VR, AR, and all the rest made to reach present day. The 1998 Sony Glasstron was appealing to that sci-fi, cyberpunk vibe of holographic screens — the "Tron" reference was quite on the nose. It was effectively a wearable monitor on your face (connected to your computer) that gave you an 800x600 screen and stereo headphones. According to the original Sony press release, it was like "watching a 30 inch screen... viewed from 1.2 meters away." Most impressive of all for the time, was a passthrough mode that's now common in every modern VR headset, like the Apple Vision Pro.

As you can imagine, it wasn't cheap. You paid $2,500 for the privilege of a device you couldn't use away from the computer. It also came with a sizable power brick/video output connector that made you feel more like someone on life support than one living in the future. There were slim few applications beyond casual computer usage, such as letting you feel like you were in the cockpit of a mech in "MechWarrior 2." Even being two-decades old technology, some people still use it today for FPV drones.

Nintendo Satellaview

Starlink with its constellations of satellites makes you feel really sci-fi downloading a game from the skies, but you'd be surprised to know '90s people did it before it was cool. The Satellaview satellite modem from Nintendo let users download games for their Super Famicom consoles way back in 1995 — although only in Japan, since the device never made its way across the pond. It cost $150, plus a subscription to Japan's St. GIGA satellite radio, the former of which translates to over $300 in today's money. Further, you couldn't download games on demand, it had to be during a Famicom Broadcasting session every evening between 4 and 7 PM.

There were quite a few options to choose from for downloading, including full games, game demos, digital magazines, and live, re-released digital audio for classic titles like "The Legend of Zelda." To be clear, these were transmitted live to your console during the broadcast. However, Nintendo's litigious hand was already beginning to show here. The games had a strict DRM that only that let players play during a broadcast, resulting in many games being lost to time and being difficult to emulate later on.

To make matters worse, Nintendo and St. GIGA weren't on the best of terms. The service was discontinued in 2000. In any case, it's fascinating to think that people were downloading games over satellite before 3D graphics arrived on the N64.

[Featured image by Muband via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 3.0]

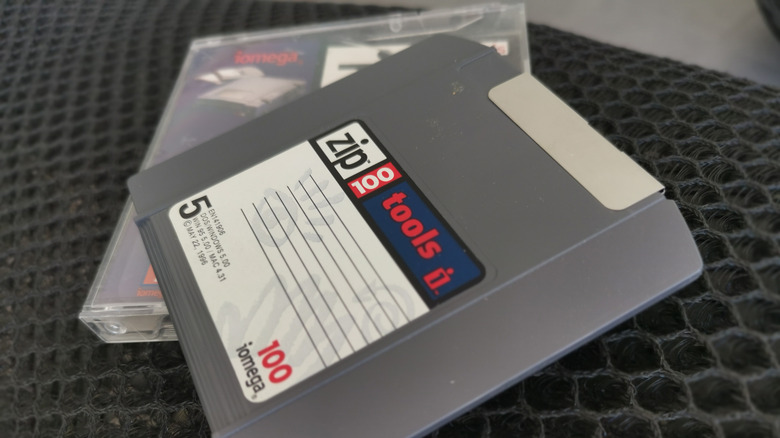

Iomega Zip drive

History's graveyard is full of competing standards where one ultimately took the throne over the other. VHS defeated Betamax, Blu-ray defeated HD DVD, and in this case, the floppy disk (kinda) defeated the Zip drive. The 1994 Iomega Zip (not to be confused with .zip compressed files) was known as a superfloppy, a high-capacity floppy disk for when that 1.44 MB wasn't cutting it. It wasn't so much a competitor to the floppy disk as a successor that the tech industry believed would replace the old standard. Zips held 100 MB at their outset, eventually reaching 750 MB — to be clear, a lot of data storage for the time.

You can probably guess what happened given that this was also when CDs were becoming the norm. Even as fairly new tech, a single CD held a girthy 650 MB. Plus, Zip drives inherited the same dust and misalignment flaws as their predecessors, which definitely helped the ensuing lawsuits after the lifetime guarantee they were packaged with turned out not be true. Computer hard drive capacity was increasing, too — limited hard drive storage had been the entire reason floppies existed, initially.

So, the Zip was a flop — pun intended. Iomega tried its hand at other products, like MP3 players and NAS solutions, but nothing stuck, and it eventually was absorbed into EMC (later Lenovo EMC).

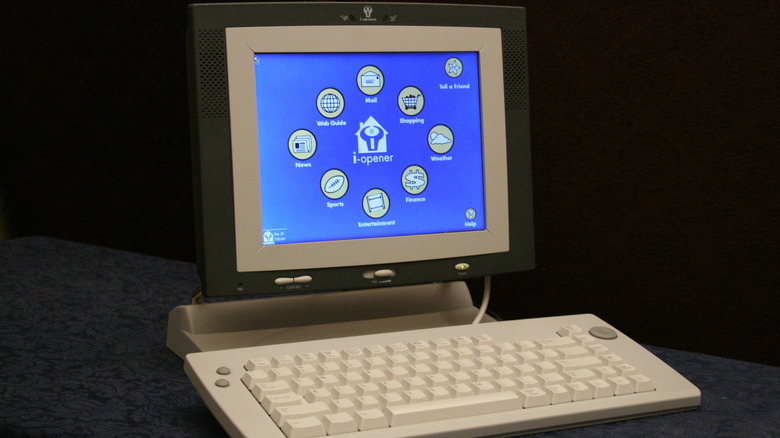

Netpliance I-Opener

If you think Silicon Valley selling hardware at a loss and trying to recoup the cost with software is a modern trend, think again — this was already happening in the '90s. The i-Opener (which sounds like a can opener sold by Apple) cost all of $99 in 1999 (despite costing $400 to manufacture) and let you browse the web or read email. However, that Internet access came only through a monthly, $21.95 dial-up subscription service from Netpliance, I-Opener's mother company.

The was just one problem — the service contract was loose enough that many people could, at least initially, get away with not paying the subscription, sort of like how people got free CDs for a penny back in the '80s from Columbia House. So effectively, I-Opener owners had a $400 computer for a quarter of the price. With locked-down devices (just look at the Spotify Car Thing) come tinkerers and hackers. BYTECellar recalls how easy it was to swap out a few parts and install Windows 98.

What ensued was a game of whack-a-mole. Netpliance tried to lock it down, and hackers found new ways to subvert them. The moles eventually won. The losses were so great that Netpliance cut 38% of its workforce in 2002 and left I-Opener for new pastures, as reported by CNET at the time.

[Featured image by Ildar Sagdejev (Specious) via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 3.0]

Frag Master controller

"Doom," the granddaddy boomer shooter of every FPS shooter out there, was one of the crowning achievements of the '90s. Mouse and keyboard ultimately won out as the best way to play FPS shooters, but before then, other PC peripherals like the trackball and the joystick vied for a spot. The Thrustmaster Frag Master was one such in 1998. Think of it as a joystick built specifically for FPS games and nothing else. It looks like the steering wheel for an alien spaceship: a triangle arch with 3 thumb buttons and 2 triggers per side. According to box art of the Thrustmaster, it was "easier to use than a keyboard and mouse."

Reviews at the time make it clear why you've probably never even heard of the Frag Master. Users claimed it was hard to aim, hard to move, and everything in between — so, definitely not a mouse and keyboard killer, at least as far as FPS games were concerned. Linus Tech Tips on YouTube took a stab at it two decades later and came to the same conclusion. An interesting and weird idea, to be sure, but clearly not the gaming revolution its designers hoped it would be.

View-Master Interactive Vision

Using VHS tapes is a core memory from every millennial's childhood. Nothing beats inserting one into your VHS player, hearing the gears pull it in, lock it in place, and start spinning, then having to rewind it after you finished the movie. However, you probably didn't know VHS had one other trick up its sleeve: interactive video games. Several versions in the '80s tried to make it work, like the Hasbro NEMO and Control-Vision. The View-Master Interactive arrived in 1988 and let kids interact with characters from "Sesame Street" and other popular IPs.

The interactivity aspect was quite impressive for the time, considering this was a VHS tape. Think choosing a number on the screen or matching singing characters to play a song. You can see it in action on the ZC-Infinity YouTube channel.

The issue was the lack of replayability (even for children who can watch a movie a million times, believe it or not) and how difficult it was to use. Those who owned one report that it was riddled with technical difficulties and had a god-awful controller, spoiling what little fun there was to be had. Cool idea in theory, bad in practice. It was discontinued in 1990, but ever since then enthusiasts have done their best to preserve it in service to the historical record.

[Featured image by Evan-Amos via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 3.0]