Mars Has Creepy Geological 'Spiders' And Researchers Have Recreated Them On Earth

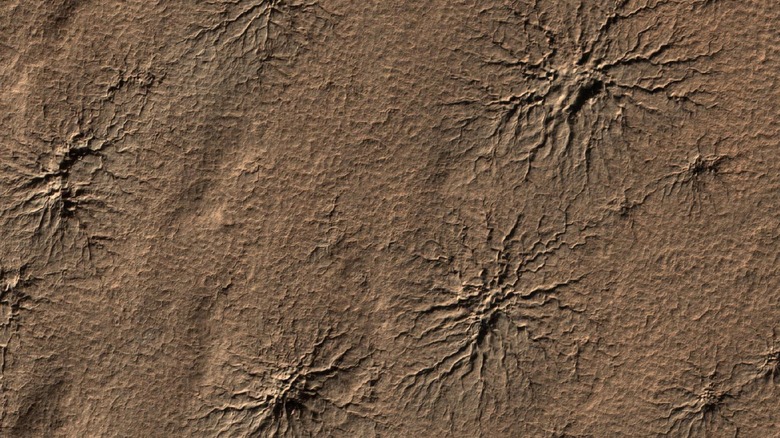

Mars has many weird geological features, from deep underground cave-like systems formed by the passage of lava to global dust storms which can cover the entire planet. It has strange features on its surface too, like bizarre looking "spiders" more formally known as araneiform terrain.

Now, researchers have been able to recreate these spider features in a lab here on Earth, showing how they may have formed on the red planet.

The research, published in a paper in The Planetary Science Journal, describes how the researchers were able to recreate the features that were first observed by spacecraft orbiting Mars in 2003. Since then, researchers have wondered about how they were formed, as they are not something which is observed on Earth.

The features can stretch as long as half a mile wide, with a central raised area surrounded by hundreds of creepy-looking legs, from which they take their name. The researchers thought that there must be something particularly about the atmosphere and pressure on Mars, which is different from that here on Earth, which was helping them to form.

Studying the features could help them to understand Mars and its climate better, as scientists gain a better idea of how Mars's unique conditions contribute to its geological features.

"The spiders are strange, beautiful geologic features in their own right," said researcher Lauren Mc Keown of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory. "These experiments will help tune our models for how they form."

How spiders are formed

The theory was that the spiders were created by the passing of the Martian seasons. Just like here on Earth, Mars has a warmer summer period and a colder winter period, though the seasons there last twice as long as the seasons on Earth due to Mars's longer orbit around the sun.

Over winter, when it is colder, ice formed of carbon dioxide builds up on the Martian surface. As the seasons change, the sun shines brighter and warmed, heating up the soil beneath the transparent carbon dioxide ice. The soil heats more quickly than the ice because it is darker in color, so the ice right by the surface will go through a process called sublimation, where it turns directly from solid to gas without going through a liquid stage.

This creates pockets of gas which sit above the soil but below other parts of the ice sheet, and this gas gradually builds up and increases pressure until it cracks the ice above it. The gas escapes upward through the cracks, carrying dust and debris with it, and leaving behind the cracked spider shape.

That explanation made sense from what scientists know about Mars and its conditions, but there was no proof that it was correct. To know if it were true, researchers had to recreate the conditions of Mars and see if they could form spiders of their own in their lab.

Making a spider in a lab

To test whether this theory was right, the researchers had to create some key conditions of the Martian environment. That meant firstly that it had to be very cold, as they were recreating Mars in the winter time, with temperatures as low as minus 301 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 185 degrees Celsius). It also needed to be very low air pressure, as the atmosphere's density on Mars is just 1% that of Earth's.

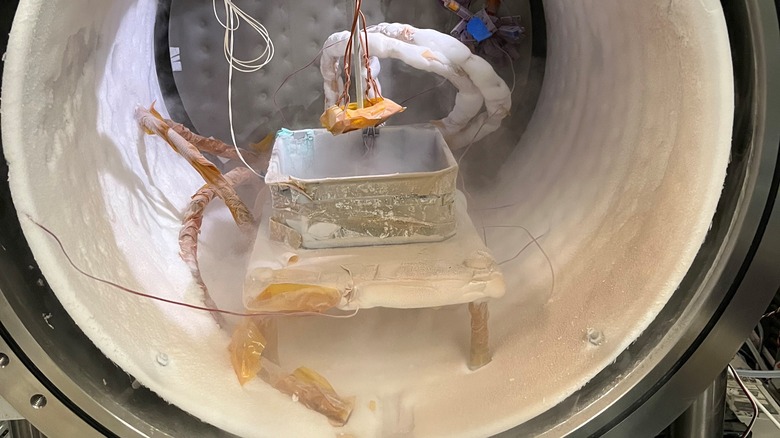

The research team used a facility at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) called the Dirty Under-vacuum Simulation Testbed for Icy Environments, or DUSTIE. As the name suggests, this chamber can be filled with dust as then cooled to very low temperatures using liquid nitrogen.

First the dust, or as it is technically called, the soil simulant, was chilled. Then it was put inside DUSTIE, and the pressure was reduced until it was comparable to that of Mars. The researchers added carbon dioxide to the chamber, similar to that found in the Martian atmosphere. Then they observed as the carbon dioxide froze from gas to ice.

To simulate the arriving warmth of summer sunlight, they then put a heater below the dust to warm it up, hoping it would crack the ice and form a spider. Eventually, it worked.

"It was late on a Friday evening and the lab manager burst in after hearing me shrieking," said Mc Keown, who has been working on this problem for five years. "She thought there had been an accident."

New details revealed

The research didn't only support the theory of how spiders form. It also revealed some new details that hadn't been predicted before.

In certain conditions, the ice formed not only in sheets on top of the dust, but also in between grains of the dust. It then cracked open the dust layer, called the substrate, which gave the spiders a slightly different look.

This only happened sometimes, and it seems to be related to the types of dust grains present and the presence of water ice underground. So there are now potentially two processes which could explain the spiders, depending on particular conditions in a location.

"It's one of those details that show that nature is a little messier than the textbook image," said fellow researcher Serina Diniega of JPL.

Now, the research team wants to make their experiment more precise by simulating heat coming from above the ice, rather than below it, as this is more accurate to the conditions on Mars.

But there are also questions that they can't answer in a lab, such as why the spiders only form in some locations on Mars and not others. Researchers will have to wait for answers to these questions, as the spiders are currently seen in Mars's southern hemisphere, far away from where the Curiosity and Perseverance rovers are currently exploring.