The History Behind The Swiss Cheese Pontiacs

Over the years, cars have been associated with food in some rather unusual ways. Lemons, of course, are those vehicles — looking at you, Ford Pinto (one of Ford's biggest car flops of all time), AMC Pacer, and Yugo — that earned a badge for being so defective they left a sour taste on consumers' palates. Nissan made the compact Cherry and Suzuki the minuscule, odd Cappuccino. Chevy is lyrically reputed to be as American as apple pie, and Oscar Mayer has the Wienermobile.

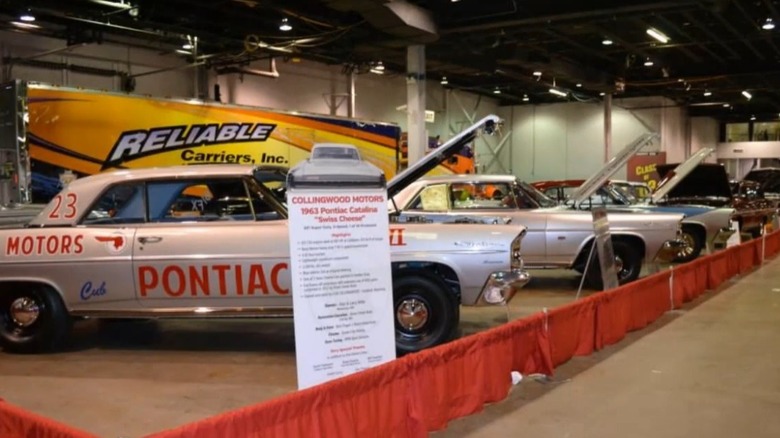

Then you have the "Swiss Cheese" Pontiac Catalinas, which weren't ordinary production vehicles meant to be driven to work, school, or the beach. No, these cheesy cars were built for one purpose — hauling down the drag strip as fast as possible. Lemons they were not.

For those not interested in drag or stock car racing, it might be a shock to learn that Pontiac was actually the chief manufacturer of NASCAR and NHRA cars in the early 1960s. The company knew that to remain king of the hill, it had to be creative and come up with ways to eke out every bit of power and speed possible from its dragsters.

For the 1963 NHRA season, Pontiac wanted to make a splash in the year-old Factory Experimental class, category B (B/FX), where manufacturers were allowed to use optional equipment — instead of just assembly-line or showroom-available parts — on stock cars.

Weight loss was the key to success

These FX cars weren't beholden to mass production rules but had to be assembled on the line like other production-ready Pontiacs and were limited to pushing 9 to 12.99 pounds per cubic inch. Quick acceleration from a standing start was the primary goal, and in order to achieve that a car had to have the perfect mix of low weight, high power, and insane tire-grabbing traction.

Pontiac took 14 of its standard 421 Catalina Super Duty cars (the smallest platform from its full-size model line) and began stripping them down. It started by removing every option not absolutely vital to the car's operation. Comfort and convenience were not the goal; raw speed and power were.

Body seals, insulation, and other soundproofing materials were all ripped out. The front sway bar was tossed because that's unnecessary in an all-out drag race down a straight strip of asphalt. Then, virtually every part made of steel was replaced by one made with aluminum – front fenders, hood, inner fender wells, radiator core support, bumpers, and bumper brackets.

Pontiac designers ditched about 50 pounds by replacing the heavy cast-iron gear cases with aluminum ones. The original iron exhaust manifolds weighed 72 pounds each, but when built with aluminum, they only weighed 27 pounds each. Even the steel center sections of the rear axle and bell housings were swapped out for aluminum.

The checkered flag waved too soon on the Swiss Cheese

Pontiac wasn't finished. It removed a lateral brace from the rectangular steel frame and drilled some 130 holes into what was left, spacing them just far enough apart to retain structural integrity. They were so fragile, two-by-fours had to be used to brace them from kinking during manufacturing.

By the time Pontiac finished carving, these "Swiss Cheese" versions weighed 3,300 pounds — almost 900 pounds less than the stock Catalinas it started with. And this worked, because in 1963 one (sponsored by Packer Pontiac in Detroit) of the 14 set the NHRA C/Stock class record with 12.27 seconds at 114.64 mph.

But something else happened that year that put the kibosh on them before they could really start melting the tires off the competition. In January, GM ordered all divisions to cease their racing support and downplay their high-performance aspects.

GM was selling over half of all the new cars in America at the time, but the timing was terrible. Before John F. Kennedy became president in 1961 and appointed his brother Robert as attorney general, the Eisenhower administration had launched an investigation into GM. Robert Kennedy believed GM was monopolizing the new-car market, violating antitrust laws, and kept the probe going. A long-held theory was that GM feared an even deeper investigation and decided to finally adhere to a 1957 agreement by the Automobile Manufacturers Association forbidding factory participation, which had been wholly ignored for years.