How Howard Hughes And The CIA Stole A Soviet Nuclear Missile Sub

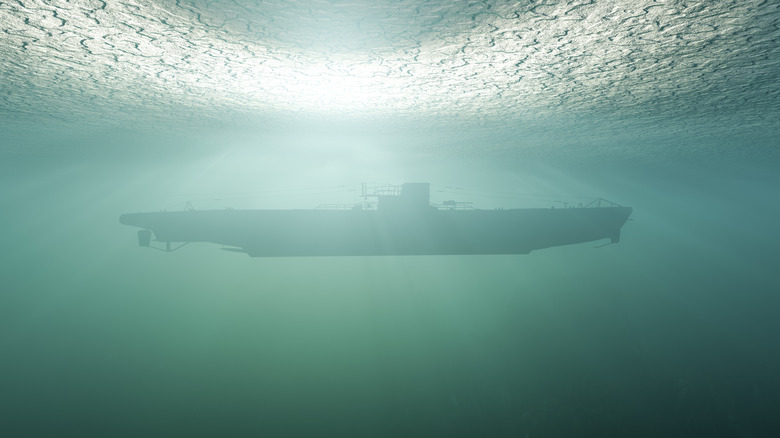

No one knows for sure what killed the 98 men aboard K-129. The Soviet hypothesis was that the ballistic missile sub accidentally slipped beneath operational depth while snorkeling. Perhaps a bad crew reaction doomed the boat. Rumors still swirl in Russia that she collided with the American submarine USS Swordfish. Other theories blame a hydrogen explosion or a leaking seal. There was just one thing all parties agreed on — the K-129 was lost, vanished two weeks into her patrol in the spring of 1968, somewhere in the depths of the Pacific Ocean.

The Cold War was at its height, with the United States and U.S.S.R. locked in a potentially apocalyptic game of nuclear brinksmanship and shadowy geopolitics. Men and women died for intelligence about the other side, from a fragment of a missile system's blueprint to an hour of advance notice of a ship's deployment. Every scrap of knowledge about the enemy's capability or intent was considered critical. Now, a Soviet ballistic missile sub — one of the most technologically advanced chess pieces of the Cold War — lay somewhere beneath the ocean's surface, up for grabs to whoever had the means and motivation to get it.

The Soviets searched for their submarine for weeks, to no avail. Ships, helicopters, and aircraft combed the proposed operating area of K-129. In the end, they had no idea of her fate. The best they could hope for was that the Americans would not catch on, but the Soviets were out of luck. A U.S. Air Force sensor designed to detect nuclear activity caught the sounds of the doomed submarine as it sank. And the Americans wanted it.

Going golfing

Throughout the Cold War, both sides developed incredible and innovative machines like the Ekranoplan hoping to pull an end run on the enemy. Initially, a weapon primarily used to cripple enemy logistics during both World Wars, the submarine had evolved dramatically by the end World War II. Beginning in the late 1950s, both the Soviet Union and the United States started building and outfitting submarines armed with nuclear missiles. The primary mission was to lurk undetected beneath the sea, assuring retaliatory annihilation to whoever dared launch a nuke.

The K-129 began life as part of the Soviet Union's Project 629. Between 1958 and 1962, Project 629 launched 23 Golf class (as later designated by NATO) missile submarines. The Golf class represented the USSR's first attempt to build a missile-launching sub from the keel up. With a length of 328 feet and a beam of 28 feet, K-129 displaced 2,700 tons on the surface and 3,200 tons submerged. A diesel-electric propulsion system gave her 22,000 miles of range and a top speed of 17.5 knots.

Though the K-129 was equipped with ten torpedo tubes, it was the trio of R-21 ballistic nuclear missiles – also known as SS-N-5s — on board that provided her sting. A Golf II sub could send those missiles, each tipped with a 2 to 3.5-megaton nuclear warhead, to targets over 700 miles away. The K-129 was dangerous, but these details were shrouded in shadow at the time of her sinking. The CIA wanted to know just how dangerous it was.

[Featured image by U.S. Navy via Wikipedia | Cropped and scaled | Public Domain]

Finding a needle in the Pacific

The Soviets gave up their search for K-129 after two months. The obvious danger was that the sunken nuclear missiles would degrade to the point of causing a disaster. Critical intelligence falling into enemy hands was undoubtedly a feared scenario, but the U.S.S.R. couldn't imagine anyone would be audacious — let alone capable — enough to raise such an enormous machine from the depths of the Pacific. Unfortunately, the Americans had already determined the location of the K-129.

With Air Force sensors indicating the approximate position of K-129, the Navy deployed a specially equipped spy submarine, the USS Halibut, on a search mission. The Halibut located and photographed the wreck with sensors and specialized equipment.

The good news was that the United States knew where the sub was. The bad news was everything else. The K-129 lay at a depth of 16,500 feet about 1,500 miles northeast of Hawaii. Up to that point, the deepest submarine salvage operation by the U.S. operation had retrieved the USS Squalus, which had sunk to a depth of 245 feet. Retrieving the missile sub from such a depth required a complete reimagining of maritime salvage. Retrieving the boat from that depth under the noses of Soviet intelligence might not even be possible.

Still, the potential technical bonanza was too tempting. Aside from learning about the nuclear missiles aboard the sub, K-129 undoubtedly contained codebooks and clues about Soviet technology such as sonar. Reverse engineering the construction methods used to build the boat could provide valuable insight into the Soviet war industry and naval capability. It was an intelligence bonanza — if only it could be salvaged.

A secret operation

The technical challenges alone seemed insurmountable, but complicating matters was the need to do it without the Soviets noticing. The USSR may not know precisely where K-129 lay, but they knew the approximate area. Any salvage operation large enough to raise it would surely attract attention, which could lead to war. The clandestine nature of the operation, coupled with the maritime environment, led to collaboration between the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and the Department of Defense. After two years of planning and study, CIA engineers and contractors developed a plan to lift K-129.

A hydraulic, ship-mounted retrieval system would lower to the seafloor and pluck the submarine from the muck. Early projections gave the mission a 10 percent chance of success. One CIA museum entry describes it as using a 1-inch steel rope to retrieve a compact car full of gold and lift it to the top of the Empire State Building without anyone noticing. Except steel lines and hydraulic lifts already existed. A machine capable of retrieving K-129 did not.

That was only the beginning of the challenge. With something like a feasible plan forming on the draft boards of engineers, the question remained — how to keep such an operation secret? The unlikely solution would be found ensconced in the suite of a Las Vegas hotel, his brilliance concealed behind a curtain of eccentricity.

Billionaire and eccentric genius

Born in Texas in 1905, Howard Hughes would become a titan of industry, daring aviator, motion picture producer, and playboy celebrity. The future American icon was no stranger to government projects, perhaps his most famous being the ill-fated Spruce Goose flying boat developed for the U.S. armed forces in the 1940s.

Struggling with obsessive-compulsive disorder, drug addiction, and ill health, Hughes went into almost complete seclusion by the early 1950s. He traveled between homes but never made public appearances. However, he continued to work. His primary contacts with the outside world came through a few trusted aides. In 1966, Hughes moved into a two-floor suite in the Desert Inn in Nevada. When the hotel's owner demanded Hughes move out in 1967, he simply purchased the hotel. He did not leave the suite for four years.

Emaciated and reclusive, Hughes ran his business empire from a 250-square-foot bedroom sealed shut with drapes and tape. Despite, or perhaps because of, Hughes's eccentricities, the CIA approached him with a proposal. They wanted to build the equipment required to retrieve K-129 under the auspices of a mining ship owned and built by Hughes.

Every secret operation needs a good cover story. Not only would Hughes' shipbuilding operation design and construct a ship capable of deploying the hydraulic claw without notice, but it would posit that its purpose was to mine manganese modules from the ocean floor. With the technological and intelligence details finalized, construction began.

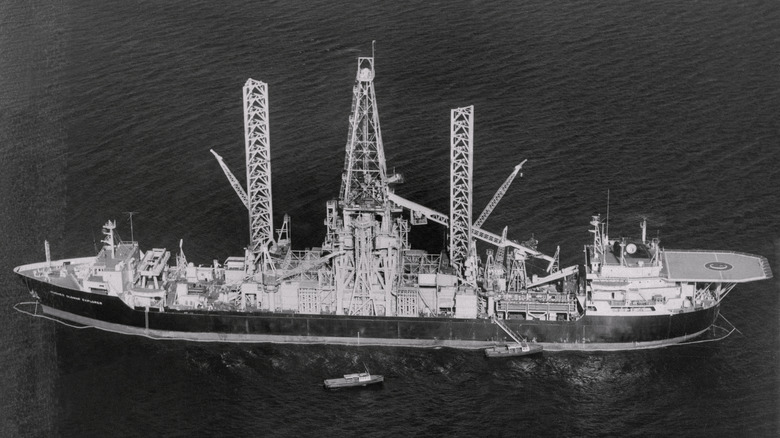

The Glomar Explorer

The Glomar Explorer was the ship at the center of the K-129's retrieval, which the CIA dubbed Project Azorian. Construction began on November 16, 1971, when the Sun Shipbuilders yard of Chester, Pennsylvania laid the keel. It was the beginning of a multi-year construction process that would result in a 600-foot retrieval ship. From the outside, nothing indicated the Glomar Explorer to be other than a deep-sea mining ship. Like other ships of that type, she needed to maintain position against wind and tide while operating heavy equipment at great depth.

It was the heart of the Glomar Explorer that raised eyebrows. With the requirement of hiding the operation from prying eyes, her center hold was a massive moon pool. The hull could open like a bomb bay, allowing for the egress of the equipment that would operate the claw. If all went according to plan, K-129 would be nestled in the moon pool, which would then drain, leaving scientists and engineers free to access the missile boat.

The second critical component of the mission was the specially designed machinery that would pull the submarine to the surface. Crewmen would lower a derrick into the water through the moon pool and, near the bottom, deploy a hydraulically activated claw that would grasp K-129 and pull her the three miles up from the bottom. The submarine weighed 1,700 tons, with the plan being to raise her in three pieces. Everything needed to go perfectly for the mission to succeed.

Under the eyes of the enemy

The Glomar Explorer reached her position over K-129 on July 4, 1974. Four days later, the operation made first contact with K-129. On August 1, operations to lift the sub commenced.

A Soviet missile ship, the Chazhma, arrived two weeks after Glomar. Suspicious, the crew of the Chazhma took photographs, even deploying a helicopter to circle the Glomar. The ships exchanged communications, with Glomar sticking to her mining story. Within four days, the Chazhma departed, but the trouble wasn't over. A Soviet naval tugboat, the SB-10, was also nearby, and it proved more persistent, loitering for two weeks and coming within 200 yards of the Glomar.

Glomar crewmen entertained themselves by filling garbage bags with worthless computer printouts and aqua lube and throwing them into the sea. Whenever a trash bag drifted across the ocean, the SB-10 would retrieve it, to the crewmen's delight. However, a particularly tense moment occurred when, with the SB-10 distressingly close, the crew pulled the capture vehicle into the moon pool. If debris from K-129 came to the surface, the entire endeavor would be sunk. Thankfully, none appeared. Eventually, SB-10 also left the area.

In the meantime, right under the noses of the Soviet vessels, the 179 by 31-foot claw attempted to snag the submarine. It was a partial success. During the sensitive raising portion of the operation, a pair of arms snapped, allowing 100 feet of K-129's nose section to fall 6,700 feet back to the ocean floor.

The Glomar response

With sections of K-129's hull being disassembled and examined in the moon pool of the Glomar Explorer, the ship departed the area on August 12, 1974. It had taken 40 days to partially retrieve the Soviet boat.

The mission was a mixed success. Some pieces of K-129 had been retrieved, but others remained on the seafloor. There was talk of a second expedition until thieves broke into the offices of the Summa Corporation, stealing documents that linked Howard Hughes and the CIA to the operation. The CIA asked the FBI for help recovering the documents, but the press got wind of the story. On February 7, 1975, the Los Angeles Times blew the secret wide open with a story detailing the audacious operation.

With the press swirling, the CIA was under pressure to issue a statement on the matter. The agency declared — in what would famously become known as the Glomar Response — that "We can neither confirm nor deny the existence of the information requested but, hypothetically, if such data were to exist, the subject matter would be classified, and could not be disclosed."

This inspired bit of semantic caginess would become the gold standard for organizations that wished to avoid outright lying while equally avoiding telling the truth. After being exposed as a spy ship, the Glomar departed for Suisun Bay, California, where, without any further tasks, she was promptly mothballed as part of the U.S. Naval Reserve. She lay idle until 1996, when Global Marine converted her to a deepwater drillship.

The spoils

Questions remain about just what the CIA gained from Operation Azorian. There is no doubt that parts of K-129 were retrieved. Six deceased submariners were found in one section and the American government presented a video of their burial at sea to Boris Yeltsin in 1992 as a gesture of goodwill.

Though press exposure has revealed parts of the operation, there is still some debate regarding precisely what the CIA learned from K-129. Subterfuge was as baked into the intelligence ethos of the Cold War as propaganda. If the enemy knows you know, then what good is the knowledge?

The CIA has remained mum on the subject, leaving historians and journalists to peck the crumbs surrounding its denial. Did the operation retrieve the critically valuable code room or any nuclear missiles aboard? If so, talking about it would hardly help the cause. If it were up to the CIA, nobody would even know there were questions to ask. They certainly did not want to answer those that were.

Whether or not American intelligence scored a jackpot of intelligence information, one thing is certain — the Department of Defense, the CIA, and Howard Hughes pulled off one of the most audacious and technologically masterful cons in the history of geopolitics. We may never know the full truth.