10 Of The Most Historically Significant Aircraft In Aviation History

From the myth of Icarus to the sketches of Leonardo Da Vinci's ornithopter, humanity has looked to the sky since first watching birds take wing. History is dotted with ill-advised attempts to achieve flight, many resulting in tragedy and defeat. It wasn't until the 18th century that humanity finally slipped gravity's bonds. Since then, every year seems to bring a revolution in air travel.

At first, aviation was the purview of a few half-mad hobbyists willing to risk life and limb to push the envelope of possibilities, but as more and more minds experienced the ecstasy of flight, aircraft became safer and more efficient. Today, we can board a passenger jet and travel between continents, view satellite photographs with a few mouse clicks, and fight wars in the skies far above conflict zones.

The story of aviation is one of exploration and discovery. It took hundreds of thousands of years for humans to leave the earth's surface, but every decade has held dozens of milestones in aviation science. Humanity is currently poised on the edges of outer space, with private enterprise eyeing the next great economic frontier: the low-earth orbit economy and commercial space. In honor of the achievements of adventurers and engineers everywhere, we take a look at ten of the most historically significant aircraft in aviation history.

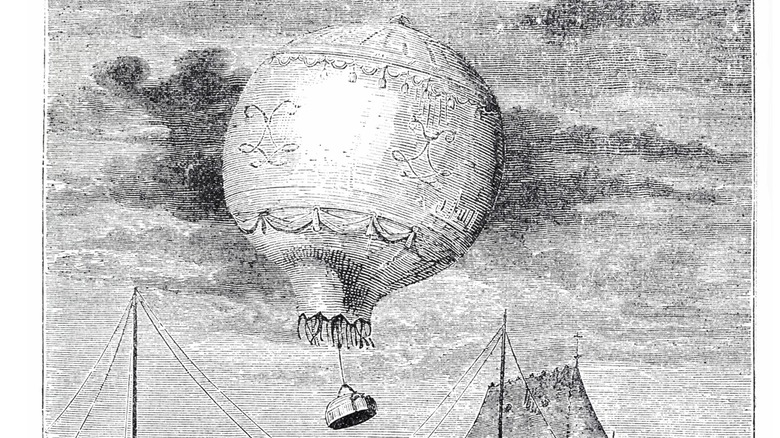

Montgolfier Brothers' Balloon

Flight first occurred at the hands of a pair of curious brothers, but perhaps not in the way you remember from history class. Sons of a prolifically fertile paper merchant, Jacques and Joseph Montgolfier were brothers born into a family of sixteen children. While working in their father's paper business in Vidalon, France, they noted that heated air collected inside a paper bag caused it to rise.

The brothers demonstrated their discovery in the public marketplace of nearby Annonay on June 4, 1783. The demonstration begged an obvious question: could this feat be accomplished with a human? After experimenting with some animal passengers, namely a duck, a rooster, and a sheep, the next milestone would be manned flight.

On November 21, 1783, in Paris, Jean-Francois Pilatre de Rozier and Francois Laurent climbed the ladder into a basket slung beneath a cotton canvas and paper balloon with a volume of 60,000 cubic feet (1,699 cubic meters). The balloon was 75 feet tall and 50 feet in diameter. De Rozier had made tethered ascents before this, learning to control the flight, but this flight would be free from any ground interference.

Laurent and de Rozier monitored the on-board fire that would heat the air and departed the earth. They achieved an altitude of approximately 3,000 feet and drifted for 25 minutes, setting down when the fire began to scorch the balloon.

Wright Flyer

Neither of the Wright brothers attended college. Instead, they went into business together as printers and publishers. Though the newspapers they published did not meet great success, they earned a reputation for the quality of the printing presses they built. They improved upon their mechanical skills by opening a bicycle shop.

A lifelong interest in flight soon led them to design gliders. After consulting the National Weather Service, they chose a site four miles south of Kitty Hawk, at the base of Kill Devil Hills, for their experiments. The consistently windy conditions and soft, sandy landing spaces were perfect for what they had in mind. Built primarily of wood and muslin fabric, the Wright Flyer had a gross weight of 750 pounds, a wingspan of 40 feet, a height of 9 feet, and a length of 21 feet. A four-cylinder, twelve-horsepower engine driving a pair of propellers would provide the thrust they needed to take wing.

On December 17, 1903 at 10:35 a.m., the Wright Flyer began a takeoff run with Orville at the helm. Easing the machine against the power of gravity, Orville took to the air. The flight covered 120 feet in twelve seconds. It was short, but it was enough. The initial flight was brief, but it proved that man could fly. The Wright Brothers could scarcely imagine the extent to which aviation would progress in the ensuing years. They had proved man could fly. It would be up to other pioneers to find out how far.

Morane Saulnier Type L

French aviator Roland Garros had been a passionate pilot for years when the First World War broke out in Europe. He was serving with the French military as a reconnaissance pilot in a Morane Saulnier Type L monoplane when he struck upon an idea. Visiting the Morane Saulnier factory, he inquired whether its engineers could install a forward-firing machine gun in the nose of his Type L. He was denied because the machine gun bullets would damage the propellor.

Garros calculated that only about 7% of the bullets would hit the blade — a margin with which he was comfortable. Installing a machine gun on his Type L, he reinforced his propellor with steel deflectors and went hunting. On April 1, 1915, Garros shot down an unarmed Albatross reconnaissance plane. Garros used his invention to shoot down two more enemy aircraft in the first three weeks of April 1915, and in doing so spawned the modern era of air combat.

Both sides adopted this new method of lethality. Advancing technology made aircraft ever deadlier, and air-to-air dogfights soon became commonplace. After landing behind enemy lines due to a malfunction, Garros spent three years as a prisoner of war before returning to battle, this time in one of the best fighter planes of all time, the Spad XIII.

Garros was killed a mere five weeks before the end of the war. Though other World War I aircraft would gain greater fame as fighters, the Type L started it all.

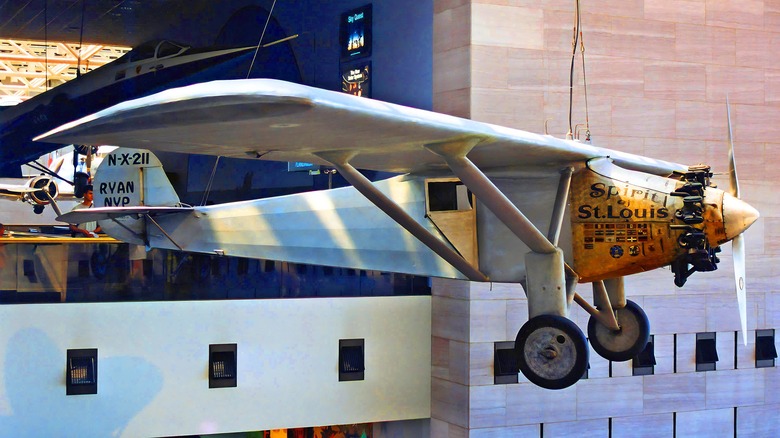

Ryan NYP

The interwar years saw continued progression in the science of aviation. As aircraft became more capable and efficient, people began to wonder at their potential. In 1919, French-born American businessman Raymond Orteig announced a prize of $25,000 (nearly a quarter million dollars in today's money) for the first non-stop New York to Paris flight.

With the financial backing of a group of St. Louis businessmen, young aviator Charles Lindbergh ordered a Ryan M-2 monoplane to attempt for the prize. Engineers worked at Lindbergh's direction to modify the M-2 for such a feat. Amongst the modifications were a rearward shift of the cockpit to improve the center of gravity and a lengthening of the wings and the fuselage. Additional fuel tanks also precluded using a forward windscreen, meaning Lindbergh could only see out the side windows in flight.

Lindbergh set a transcontinental record flying the plane from San Diego to New York in preparation for the oceanic voyage. On May 10, 1927, Lindbergh took off from Roosevelt Field in Long Island, New York. Destination: Paris. After a grueling 3,610-mile flight over thirty-three hours and thirty minutes, he landed at Bourget Field near Paris. An ecstatic crowd of 100,000 cheering Frenchmen welcomed the sight of his Ryan NYP coming in to land. More commonly known as the Spirit of St. Louis, the Smithsonian Institute owns the aircraft. It is currently is displayed at the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C.

Douglas DC-3

The Douglas DC-3 is the first profitable passenger-carrying aircraft in commercial aviation history. In the interwar years, air travel became safer and more feasible as a mode of transportation, and much of this was due to the DC-3's success.

A bigger version of the DC-2, the DC-3 could carry 21 passengers a distance of 1,500 miles (and even farther with additional fuel tanks). It was the first passenger aircraft to cross the United States in a single day. It had a wingspan of 95 feet, a length of 64 feet, and a height of 16 feet. A pair of Wright SGR 1829-71 1,200 horsepower engines pushed it to speeds of up to 230 mph.

The DC-3 was later adapted for military use, serving an essential role in the Second World War as a troop transport and supply plane. The military version of the DC-3, the C-47, carried airborne troops into Normandy on June 6, 1944.

Pilots loved the DC-3's ability to take off, cruise, and land with a low stalling speed. Reliability and ease of maintenance made repairs relatively simple, keeping DC-3s flying for decades. Though DC-3 production ended in 1945 after 13,000 aircraft were produced, there are still examples in flight today. As recently as 2015, the United States Forest Service retired its last operating DC-3 aircraft.

FW-61

Legendary aircraft designer Henrich Focke may be associated with the FW-190 fighter aircraft of World War II, but his other claim to fame is more significant. After serving in the First World War, he trained as a mechanical engineer at the Hanover Technical Academy. In 1924, Focke, Dr. Werner Naumann, and Georg Wolf began the Focke-Wulf Aircraft Manufacturing Company. Focke resisted pressure from the rising Nazi party to mass-produce military aircraft. Forced out of his own company, he gathered an engineering party with a different aim: to create a vertical take-off aircraft.

Airplane wings create lift by forcing air over the top of the wing faster than the bottom, creating a unique shape called an airfoil. On fixed-wing aircraft, thrust creates lift by forcing air over the wings by moving the aircraft forward. Helicopter rotors are airfoils, but instead of pushing the entire craft forward, the rotors spin to create airflow over them, allowing the craft to take off vertically.

Focke's first helicopter, the FW-61, underwent tethered testing in 1935. The twin-rotor craft was ungainly. With twin rotors extending from a fuselage where the wings typically were on a propellor-driven aircraft, the FW-61 was powered by a Bramo engine and could reach 62 miles per hour.

Since then, helicopters have become a separate wing of aviation, serving as transport vehicles, weapons of war, and rescue vehicles by going to a million places fixed-wing aircraft cannot access.

[Featured image by ADL via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 3.0]

Supermarine Spitfire Mk. 1

By the summer of 1940, German forces had swept through Western Europe to the coasts of France. Across the English channel, England remained the sole nation in defiance of Hitler's proposed new world order. If Germany could bring the British to heel, Hitler would be free to unleash his military forces however he pleased. The head of Germany's mighty Luftwaffe, Herman Goering, assured Hitler his aircraft force would pummel the British into submission. The British had two primary tools against the Luftwaffe: a highly secret, comprehensive radar early warning system and one of the most innovative WWII planes, the Supermarine Spitfire.

History buffs will lament that the Hawker Hurricane doesn't get its due, and they're not wrong. The Hurricane was one the RAF's most notable fighters of the Battle of Britain, but it was the Spitfires tangling with the cream of Germany's crop and protecting the Hurricanes from BF-109 fighter escorts as they attacked the bomber formations that terrorized England.

Designed by R.J. Mitchell, the Spitfire was in development as far back as 1934. It first took flight on March 5, 1936. By the summer of 1940, it was armed with four .303-inch Browning machine guns in each wing and powered by a Rolls-Royce-produced Merlin engine. It was the only plane in the Royal Air Force that could go toe-to-toe with the BF-109.

Though other aircraft would come along to bring the Nazi menace to its knees during the desperate fighting of the summer of 1940, it is safe to say the Spitfire may have staved off years of Nazi domination.

Bell X-1

The rise of the jet age represented every bit as revolutionary a change in aviation as the Wright brothers' flight. Operational jet engines first appeared in 1940s aircraft, such as the Gloster Meteor and ME-262. With the end of World War II and the rise of the Cold War, scientists in the United States used this new technology to push the envelope of the impossible.

On October 14, 1947, A Boeing B-29 flying at 23,000 feet opened its bomb bay doors and ejected a sleek, bright orange aircraft. It had a wingspan of 28 feet, a length of 31 feet, and a weight of 13,034 pounds. The Bell X-1, named "Glamorous Glennis" after the wife of its pilot, fighter ace Chuck Yeager, employed a bullet-shaped fuselage with ultra-thin wings and adjustable stabilizers.

A rocket ignited in the tail of the experimental Bell X-1, and it climbed to test altitude. Its mission was dangerous and completely unprecedented: to exceed the speed of sound. Many believed that any craft traveling that fast would break up upon reaching the sound barrier. Yeager and the X-1 were on a path to find out.

The X-1 used an XLR11 liquid-fuel rocket engine making nearly 6,000 pounds of thrust to accelerate Glamorous Glennis to a speed of 700 miles per hour and an altitude of 43,000 feet, breaking the sound barrier with a sonic boom and accomplishing his mission.

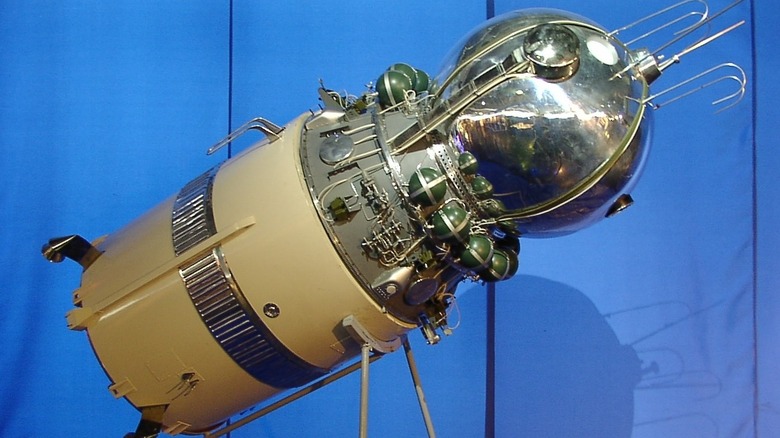

Vostok 1

The race to the first manned space flight ended on April 12, 1961, when Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin achieved orbit from the cockpit of the Vostok 1. The first space flight was steeped in the mythology and competition of the Cold War, with the United States and the Soviet Union vying to outdo the other's scientific achievements. One of the main areas of this conflict was mastery of space flight.

The Vostok 1 spaceship included a spherical descent module named the 3KA-3 attached to a three-stage 8K72K rocket based on an R-7A intercontinental ballistic missile. The module housed Gargarin in an ejection seat along with the engine system, communication devices, and manual controls. Due to concerns over how weightlessness would impact Gargarin's ability to function, ground control locked the controls, retaining the module's command for the entire flight.

Blasting off from the Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan, Gargarin completed a single orbit of Earth in 1 hour, 48 minutes. Because the module's re-entry speed was so great, Gargarin had to eject at 23,000 feet altitude, floating back to Earth on a parachute.

Though the Americans sent astronaut Alan Shepard Jr. to space less than a month later on May 5, 1961, the Vostok 1 is cemented as the point in aviation history when humanity first encountered the infinite.

[Featured image by HPH via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 3.0]

SR-71 Blackbird

The fastest air-breathing aircraft in history, Lockheed's SR-71 captured the public's imagination not just for its sinister looks but the time it spent in the service of the United States. During the Cold War, the Soviet Union and the United States went to incredible lengths to spy on the enemy. The SR-71 was born from a need for a reconnaissance aircraft that could fly higher and faster than Soviet air defense missiles.

Lockheed's Skunkworks first put the Blackbird, as it became known, in the air with test pilot Robert Gilliland at the controls on December 22, 1964. It was incredibly fast. During testing, the SR-71 achieved Mach 3.4, more than triple the speed of sound. Flying at altitudes of up to 85,000 feet, no surface-to-air-missle could get close to downing an SR-71. The stealth jet set an official speed record on July 27, 1976, when it achieved 2,193 mph.

The SR-71 served in the United States Air Force between 1964 and 1989, flying its final operational mission in October of that year. On March 6, 1990, an SR-71 set a transcontinental record when it flew from Palmdale, California to Washington, D.C. in 68 minutes.