Aircraft Carriers In The 1860s? The Civil War Saga Of The Steamboat Fanny

Which of these terms does not belong: Gettysburg, secession, cavalry charge, musket fire, or carrier-launched aerial reconnaissance platform?

Most slot nicely into what we remember about the American Civil War from history class, but that last one jumps out. It's something that would fit into a conversation about military capabilities today. How could there be an aerial reconnaissance platform, let alone an aircraft carrier, more than forty years before the Wright brothers took off at Kitty Hawk?

It took decades for naval warfare to take to the sky, but the process actually began far earlier than most people think. Aerial combat between powered planes may not have started until World War I, but the truth is that adventurers and inventors were taking to the sky long before that. Getting a heavier-than-air craft off the ground wouldn't happen until the 20th century, but manned lighter-than-air craft flew as early as 1783.

An aircraft carrier? During the Civil War? That's a pretty tall claim, and perhaps it's a bit grandiose. Still, by definition, an ignominious little steamship named the Fanny became the world's first self-propelled aircraft carrier.

The tumultuous life of the Fanny

The Fanny was not supposed to be historic. Like so many of the small boats that served one cause or another during the Civil War, she should have been relegated to the fate of an anonymous wreck in a muddy river bank somewhere. However, as is often the case when history happens, she was in the right place at the right time.

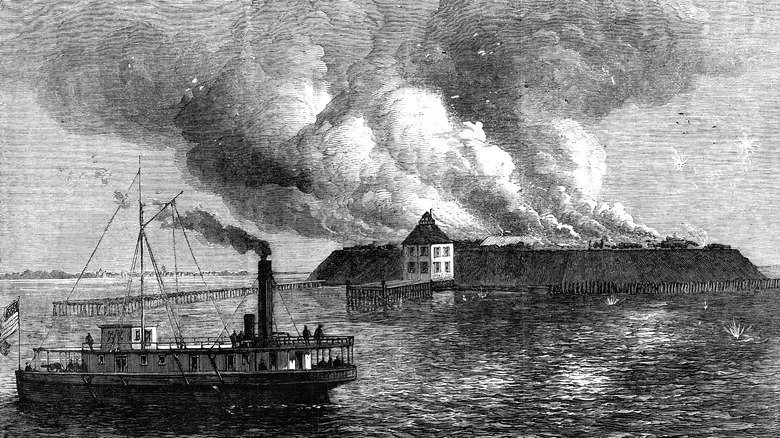

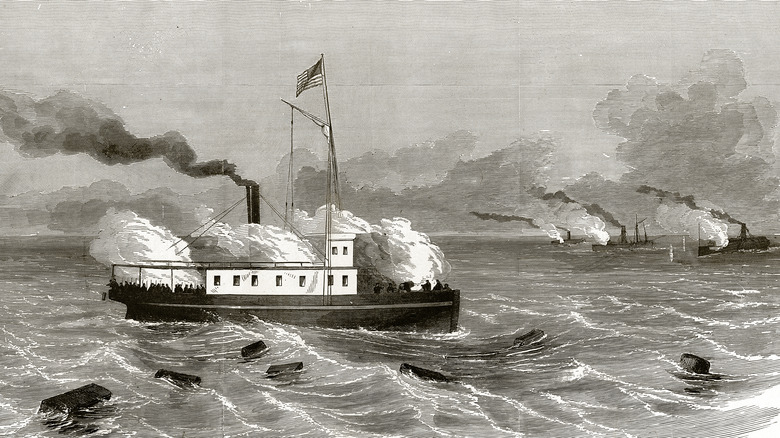

The Fanny was a wooden-hulled screw steamer originally part of the United States Navy. Christened the USS Fanny and pressed into service, the plucky boat established a solid war record by transporting troops in August 1861 during the first amphibious operation of the Civil War. She and two other transports carried about 900 Federal troops from Hampton Roads, Virginia, to Hatteras Inlet, North Carolina. Though exciting, the Fanny's career was brutally short. During an engagement on October 1, 1861, Confederate naval forces captured the Fanny. The boat went on to battle against its old allies as a Confederate ship.

There's not much to set the Fanny apart from countless other naval ships that served in the Civil War, except for one important feat. The story of how a little steamship named Fanny became the world's first aircraft carrier begins in the 18th century with a pair of curious Frenchmen.

The true first manned flight

Great feats of aviation history can earn pilots fame and fortune. Consider the Wright Brothers, Charles Lindbergh, Chuck Yaeger, or Yuri Gargarin. These pilots have become household names. Not so much for Jacques and Joseph Montgolfier.

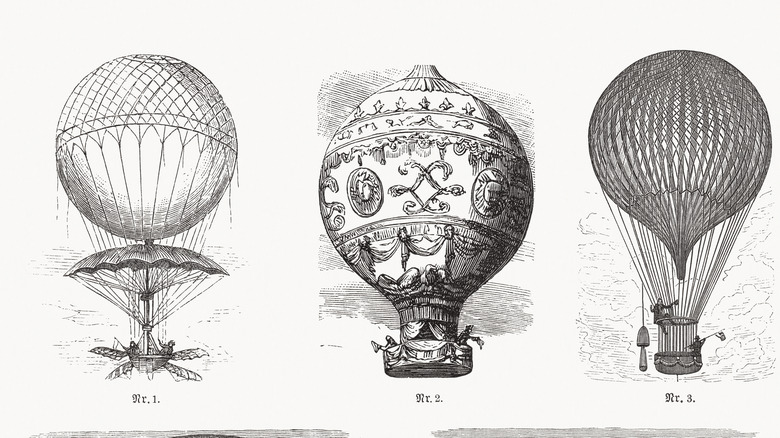

Born in southern France as two of 16 children of a prosperous paper merchant, Jacques and Joseph shared a keen curiosity about the world. While working for their father, the brothers noted that heated air trapped in a paper balloon caused the balloon to rise. They first demonstrated this principle at a local market on June 4, 1783. The balloon rose to about 3,000 feet, hovered for ten minutes, and settled down a couple of miles away.

Encouraged, the brothers began sending live animals aloft. Sheep, roosters, and ducks all enjoyed a ride courtesy of the Montgolfier brothers. However, it wasn't until November 21, 1783 that two men, Francois Pilatre de Rozier and Francois Laurent, climbed aboard a circular platform and, hand-feeding a fire through the balloon's skirts, lifted off. They soared over Paris at about 500 feet of altitude before setting down on a farm 25 minutes later, having covered nearly six miles.

Manned flight proved irresistible to scientists and adventurers alike. A mere ten days after de Rozier and Laurent landed, French physicists Jacques Charles and Nicholas Robert introduced a gas balloon that got its lift from hydrogen, a lighter-than-air gas. The inaugural flight lasted nearly 3 hours and covered 25 miles. With that, the age of flight had arrived.

Balloons at war

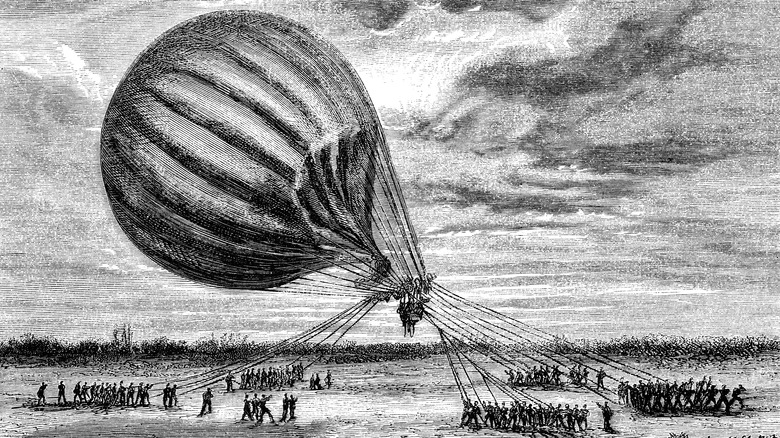

It didn't take long for the powers that be to recognize ballooning's potential for use in military scenarios. A lofty view of enemy lines, preparations, and troop movements is valuable information on the battlefield — and what better way to gain that information than a viewing platform high in the sky? Even in today's hyper-technological world, spy balloons are still used for effective sky reconnaissance, though the current technology is a little more advanced.

In addition to the Montgolfier brothers, France claims the first recorded use of balloons by military forces in history. The revolutionary French Committee of Public Safety created what is likely the world's first air force, the Corps d'Aerostiers, in 1794. Its mission was to observe the battlefield. While used infrequently, the corps saw action at some of the battles during the French Revolutionary Wars, including Fleurus and Charleroi.

Ballooning didn't immediately change warfare. It was fringe at best, looked down on by professional soldiers distrustful of unproven technology. Yet military and civilian enthusiasts alike continued to push the edges of the new technology.

Jean-Pierre Blanchard piloted the first flight across the English Channel in 1785. Eight years later, he would captain the first manned flight in America, taking off in Philadelphia under the watchful eye of George Washington, who viewed the launch. The flight rose to 5,800 feet and later landed safely in New Jersey.

Professor Thaddeus Sobieski Constantine Lowe, Chief Aeronaut

Thaddeus Sobieski Constantine Lowe was born in 1832 in Jefferson Mills, New Hampshire. Curious and intellectual, Lowe would make a success of himself despite lacking formal education.

After attending a lecture on lighter-than-air gas in 1850, Lowe joined Professor Reginald Dinkelhoff as an assistant. A combination of carnival barker, scientist, and pilot, Lowe was not alone in his fierce advocacy for ballooning. Several professors and pilots, amongst them an aeronaut named John LaMountain, experimented with balloon flight.

When the war started in April 1861, Lowe was preparing for a balloon flight that would take him from Cincinnati, Ohio, to Washington, D.C. Winds blew him off course, and he landed in South Carolina, where he was accused of spying for the Union. Convincing the Confederates he was no threat, Lowe returned to Cincinnati, where he was promptly summoned to Washington — someone had taken note of his misadventure.

Lowe waited for his appointment with Abraham Lincoln for a week. In the meantime, he told anyone who would listen about the marvelous potential of his balloons. Rumors swirled of an aeronautical corps, the chair of which would be vied for by many prominent balloonists. Lowe's demonstration convinced Lincoln of the value of balloon reconnaissance, so he named Lowe the Chief Aeronaut of the Federal Army. From July 1861, Lowe would lead the Balloon Corps, a concerted effort to employ balloons in the war.

The first aircraft carrier

By the time of the Balloon Corps was established, the little steamship Fanny was still at the beginning of her career. Still a part of the Union, she had yet to undergo her exciting adventures in North Carolina and was still months away from her capture. In the summer of 1861, the Fanny was stationed around Hampton Road, Virginia — later the site of the first ironclad battle between the Monitor and Virginia – under the command of Major General Benjamin Butler.

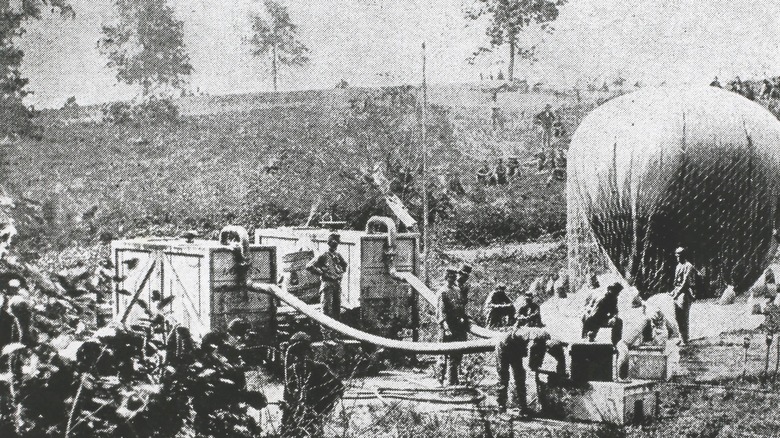

Butler needed information about the Confederate plans and fortifications around Hampton Roads, Virginia. He contacted balloonist John LaMountain, himself hoping for the Chief Aeronaut position. Arriving on July 25, 1861, LaMountain made his first successful flight on the 31st, taking his balloon up to 1,400 feet. Another foray on August 1 gave him a bird' s-eye view of the Confederate emplacement at Young's Mill, allowing him to deliver approximate troop numbers to Butler.

LaMountain and Butler scheduled another flight for August 3. Eager for a new viewpoint, LaMountain commandeered the Fanny for duty. Under the power of steam, Fanny became the world's first powered aircraft carrier when she crept into the middle of the river. She was the first such craft to launch an aircraft when LaMountain ascended from her deck to 2,000 feet, observing enemy activity around Sewell's Point.

After a similar mission on August 10, LaMountain was just as pleased with his results but was out of hydrogen. Before departing, he told Butler he would return with a balloon that would not just observe but destroy Norfolk.

The fate of the Balloon Corps

It was not to be. By the time LaMountain returned to Fort Monroe, Thaddeus Lowe had already been named Chief Aeronaut of the Balloon Corps. In addition, General Butler was gone, replaced by General John Ellis Wool, who had little interest in LaMountain's services.

However, LaMountain's feat lived on. Chief Aeronaut Lowe later created the world's first carrier battle group when he equipped a 122-foot-long barge named the George Washington Parke Custis for balloon launches. Accompanied by gunboats Tioga and Port Royal as well as an armed ship called the Delaware, the armada provided a base for Lowe's primary balloon, the Intrepid. Land-based balloons also continued to be used during the war's early battles.

Despite its purported utility, the Balloon Corps did not last the war. Both the Confederate and Union militaries launched reconnaissance balloons during the war, though any passion for them faded quickly. Many generals viewed them as a dangerous gimmick more than anything else, and it took a brave man to ascend in a plainly visible, largely stationary craft under the eyes of bored artillery crews.

LaMountain met with little success, although he continued to contract with the army privately. He ultimately joined Lowe's Balloon Corps, but the men did not get along. While remaining a faithful balloonist, the corps was ultimately doomed. After a persistent bout of malaria coupled with military resistance and a poor working relationship with his military liaison, Lowe left the Balloon Corps on May 7, 1863. He went west, where he met with great success as an inventor and a banker.

What of the Fanny?

While the Fanny may not share the same spotlight as the Spirt of St. Louis or be moored next to the USS Constitution, she holds a unique place in history. She may not have a grand display in a naval museum, but on August 3, 1861, she etched her name in history.

So what happened to the Fanny? Her career as an aircraft carrier ended nearly as soon as it began. After her Confederate capture, she was pressed into service against the Federal navy. Hit by a Federal shell from the USS Commodore Perry at the Battle of Elizabeth City, her crew ran her aground and set her afire on February 10, 1862. Her bones, presumably, are buried in the muck somewhere off the coast of New Jersey.

The Fanny appears as a mere blip on the historical radar, but her role as a ferry to an adventurous man and his curious materials marks her as a point in history. It would take decades longer to develop heavier-than-air-flight and the aircraft carriers we know today, but the ill-fated Fanny marks a confluence of ideas, experimentation, and the instant in which two worlds collided to make something that had not been there before — the aircraft carrier.