10 Patents That Made Their Founders Rich

Estimating patents' financial gain can be difficult, but they are often foundational building blocks toward broader commercial success. This is true of Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg, who received U.S. Patent No. 8,225,376 for "Dynamically generating a privacy summary." This patent, filed July 25, 2006, may not have remunerated Zuckerberg directly, but it was a crucial step toward establishing Facebook, the linchpin of his billion-dollar fortune.

Amazon's Jeff Bezos has filed numerous patents, for outlandish things like airbags on smartphones and beyond. However, in 1999 the online retailer patented its more straightforward one-click buying process, enabling users to buy products without re-entering personal data. Bezos was already worth around $7.8 billion at the time, but by the time the patent expired in 2017, the mogul's fortune had multiplied to reach $72.8 billion. Again, the patent's role in this can only be estimated, but the exclusive convenience it provided Amazon was unquestionably good for business.

However, the value of some other patents are much clearer to assess, especially when they are related to inventors such as George Westinghouse, Thomas Edison, Lonnie Johnson, and Chester Carlson, whose innovations shook up industries, workforces, and their bank accounts. Here are 10 patents that made their founders rich.

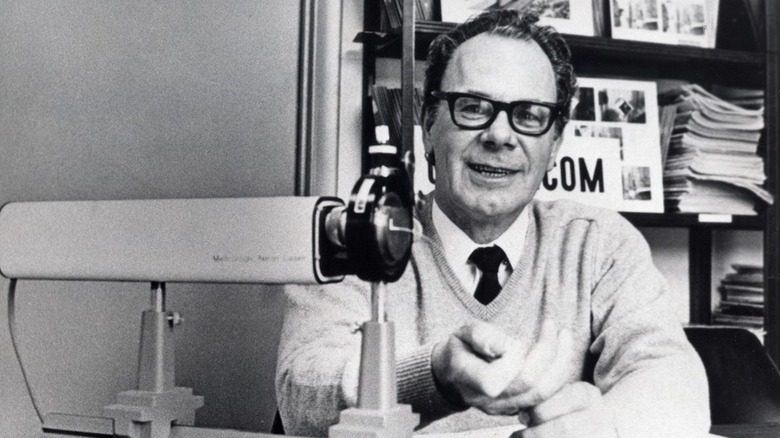

Laser — Gordon Gould

The laser, an acronym for "light amplification by stimulated emission of radiation," is truly omnipresent. To name just a few functions, lasers scan groceries, transmit data, and perform a variety of medical functions, from whitening teeth and reshaping corneas to reducing inflammation and killing cancer cells. Heck, the British Navy even uses lasers to destroy drones.

There are several threads to the laser's history. Albert Einstein theorized the technology in his 1917 paper "The Quantum Theory of Radiation." Decades later, in 1951, Charles Townes worked with his students on the "maser," an acronym for "microwave amplification by stimulated emission of radiation." In August 1958, Townes and his brother-in-law, Stanford professor Arthur Schawlow, published their research in Physical Review. Two years later, Townes and Schawlow were granted a patent for their "optical Maser."

However, there was an outlier named Gordon Gould, a chain-smoking communist who was the rakish counterpart to Townes' patrician identity. The pair knew each other and Gould had shared with Townes his ideas about "optical pumping," which Townes used in his "optical Maser" patent. Gould was ahead, though, for he had coined the term "laser" and written the basis for the technology in November 1957, nearly a full year before Townes and Schawlow's article in Physical Review.

Gould's ignorance of the patent process allowed Townes and Schawlow to get ahead, but Gould challenged their patent in 1962, beginning a 30-year struggle that would end, 23 years later, with Gould winning powerful, industry-wide patents and a payout of some $46 million.

[ Featured Image by Union College files via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 3.0 ]

Intermittent windshield wiper — Robert Kearns

Before 1969, most cars had windshield wipers that struck water away at a single, constant speed. This rigid system could affect visibility, especially for partially sighted motorists like Robert Kearns, a Ford engineer who lost sight in his left eye to a champagne cork on his wedding night.

On a rainy drive in 1962, Kearns thought about how the human eyelid wiped across the eye like a windshield wiper, only intermittently. He saw no reason why windshield wipers couldn't have the same intermittent function, so Kearns developed a working prototype using off-the-shelf parts, including a capacitor to regulate the interval between wipes.

Kearns patented the technology in 1967 and planned to sell it to Ford via the Tann Corporation. Naturally, Kearns guarded the details of his invention, but Ford claimed that he was legally bound to explain the wiper's inner workings because it was a safety feature. Kearns did so and months later, Ford announced it was using its own, in-house wiper.

Years later, in 1976, Kearns disassembled one of Ford's wipers and found that it was essentially a replica. The deception caused Kearns to suffer a nervous breakdown that sent him to a psychiatric ward for several weeks, turning his hair white with anguish. Kearns sued Ford and other automakers in 1978 for patent infringement, beginning a bitter legal battle that would bring him pain, divorce, and $10 million. It was one of the greatest David and Goliath battles in American patent history.

Dual Cyclone vacuum cleaner — James Dyson

In the late 1970s, James Dyson built an industrial cyclone tower that used centrifugal force to separate paint particles from the air. Sometime later, during a round of household chores, Dyson cursed his vacuum cleaner and its filthy, clogged bag. It was amid this frustration that the young engineer and art graduate wondered if cyclonic technology could be applied to the humble vacuum cleaner.

In 1980, Dyson patented the Dual Cyclone vacuum cleaner, a centrifugally powered device that became the world's first machine to collect dust without a bag and without losing suction.

Dyson fine-tuned his design over 5,127 prototypes, but British industry refused to back the young inventor's work because it threatened the lucrative vacuum bag market. In 1983, Dyson released the G-Force vacuum cleaner in Japan, winning the 1991 International Design Fair Prize. To crack the British market, Dyson launched his own eponymous company and released the DC01 in 1993, the company's first wide-release product and the beginning of a global phenomenon.

Dyson's Dual Cyclone patent is the foundation of not just the DC01 but the inventor's entire company. Dyson has built on this seminal patent, developing the Airblade hand dryer, the Corrale hair straighteners, the Cool tower fan, and the N526 prototype electric vehicle. Dyson's reputation for quality and innovation has generated billions in revenue, earning its founder a net worth of some $13.5 billion.

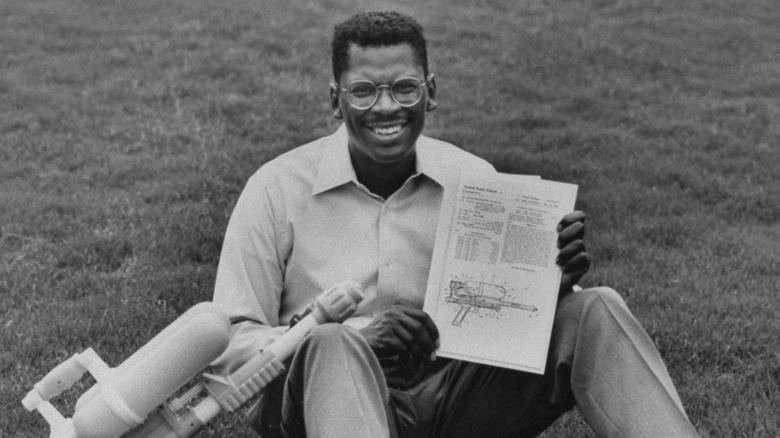

Super Soaker — Lonnie Johnson

A nuclear engineer assigned to NASA's Galileo mission, Lonnie Johnson came up with the Super Soaker in 1982 during some after-hours work in his basement bathroom. When the inventor attached a heat pump to his sink, a rush of water jetted through the pump and shot across the room.

"I thought to myself geez, this would make a neat water gun," Johnson explained to Marketplace, "So I decided to put the hard science stuff behind and start working on some really fun stuff." After making a prototype with plexiglass, PVC piping, and a two-liter soda bottle, Johnson secured a patent on May 27, 1986, and sought to establish a production line.

However, a $200,000 upfront investment for the first 1000 items caused Johnson to pitch his creation to toy companies. After seven years of dead ends and broken deals, the inventor licensed the "Power Drencher" to Larami Corporation, whose advertising team renamed it the Super Soaker.

Johnson's patent took off in 1991, selling two million guns. The Super Soaker would become the best-selling water toy of all time, entering the American National Toy Hall of Fame and netting Johnson over $73 million.

Telephone — Alexander Graham Bell

Alexander Graham Bell patented the first telephone, one of a handful of inventions that arguably shaped the modern world, on March 7th, 1876. The technology consisted of a mouthpiece, a diaphragm, and an electromagnet that turned sound waves into electric signals that traveled through cables to the recipient telephone, where the signals returned to sound waves and emerged from the mouthpiece.

In 1877, Bell established the Bell Telephone Company, securing a 33% ownership stake. The partners attempted to cash out with a $100,000 sale offer to Western Union, but the telegraph company declined. This decision was a huge misstep for the future money transfer specialist, as Western Union later valued the patent at a staggering $25 million.

Bell never built the extreme wealth of John D. Rockefeller or Andrew Carnegie, but his telephone patent was still highly lucrative. By the end of the 19th century, Bell was worth around $1 million (approximately $30 million in 2024 dollars), placing the inventor among a privileged few who enjoyed great success in both their field and their finances.

Velcro — George de Mestral

Swiss engineer George de Mestral patented the hook-and-loop fastener, better known as Velcro, in 1955. Like other ideas created almost by accident, De Mestral thought of it during a country walk in 1941, when he noticed burr seeds sticking to his socks, coat, and dog. He took several of these burrs and put them under a microscope, revealing the tiny hooks that wove into the fabric and fur.

De Mestral recognized the synthetic potential of this mechanism. Over the next eight years, Mestral experimented with various materials and settled on nylon, a recently invented material. Under infrared light, de Mestral sewed thousands of tiny nylon hooks into fabric strips and produced a working prototype that Mestral named Velcro, a blend of "velours" (velvet) and "crochet" (hook).

After securing a patent in 1955, de Mestral established a company — Velcro SA — and introduced his invention to the world. A 1959 fashion exhibition at New York's Waldorf Astoria Hotel displayed Velcro in numerous fashionable applications, causing the New York Times to proclaim "the end of buttons, toggles, hooks, zippers, snaps and even safety pins."

The Times was hyperbolic but Velcro was here to stay. NASA strapped it to spacesuits and anything that needed to be kept in place in low gravity conditions. A year before the moon landing, in 1968, Puma became the first major supplier of Velcro-fastened sneakers; Adidas, Reebok, and many other sporting brands followed.

De Mestral's net worth is unclear, but his patent created an international company that, during his lifetime, employed thousands of people and generated many millions of dollars.

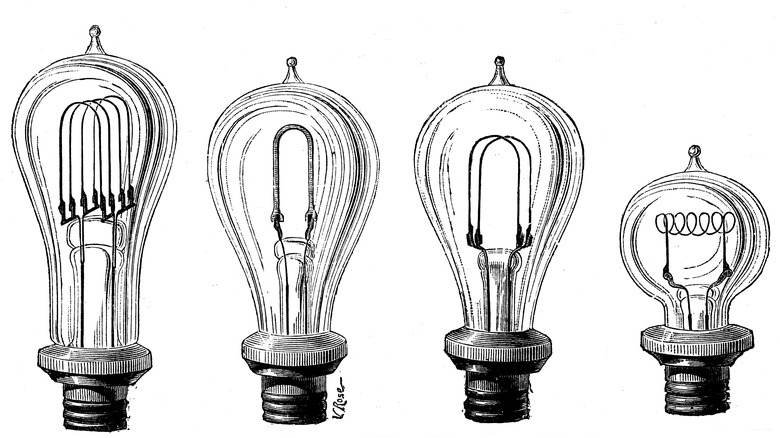

Incandescent light bulb — Thomas Edison

Thomas Edison secured a patent for his famous incandescent light bulb on January 27, 1880, some 39 years after Frederick de Moleyns'1841 patent for an incandescent lamp, which used an electric current to heat powdered charcoal between two platinum wires in a glass tube. De Moleyns had joined Humphry Davy and Warren de la Rue in producing an early electric light source, but Moleyns' lamp was neither reliable nor affordable. In 1879, a year before Edison's patent, Joseph Swan produced a new lamp that used a carbon filament but these also burned too quickly to be commercially viable.

To finally make the lightbulb a sustainable tool, Edison's team tested around 6000 different materials, including established lightbulb metals such as platinum. Eventually, Edison's team produced a carbon filament made from cotton, linen thread, wood splits, and coiled paper. Then, months after the patent was granted, Edison's Menlo Park scientists discovered a carbonized bamboo filament that boosted a lightbulb's longevity to some 1200 hours.

Incandescent lightbulbs are banned in the U.S. these days, but Edison's invention revolutionized the United States and the world, illuminating factories, offices, homes, and the streets between them. It also bolstered Edison's enduring fame and contributed to an estate worth some $12 million upon his death on October 18, 1931.

Xerography — Chester Carlson

After education at the California Institute of Technology and a graduate job at the Bell Telephone Company, Chester Carlson settled in the patent department of P.R. Mallory Company. There, Carlson wanted a way to copy the many original patents he was examining, but no adequate technology existed.

In 1934, Carlson resolved to develop his own method, and four years later on October 22, 1938, he invented electrophotography, the original name for what is now called xerography. Carlson patented the invention and took it to numerous companies, all of which turned him down. After some 20 rejections, Chester began a working relationship with Battelle Memorial Institute in 1944 and the Haloid Company — soon to be known as Xerox — in 1947.

In 1959, Carlson's 19-year effort of ingenuity, engineering, and exhaustive pitching materialized with the Xerox 914 copier, a landmark product that sold in huge numbers through the 1960s. The rate at which the 914 proliferated was truly astounding. In 1955, the world made around 20 million non-xerographic copies. In 1964, just five years after the 914's release, xerography had increased the world's copy rate to around nine and a half billion. All of this made Chester Carlson a very wealthy man. In 1968, Forbes estimated Carlson's fortune at $150 million, but Carlson claimed his fortune was in the "0 to $50 million bracket." It may well have been closer to zero because the inventor donated an estimated $100 million to numerous philanthropic endeavors.

Air brake — George Westinghouse

Inventor, entrepreneur, and industrialist George Westinghouse held over 300 patents, including the life-saving locomotive air brake, which centralized locomotive braking systems. The device was patented on April 13, 1869 and enabled train operators to trigger every brake on every carriage from the vehicle's cab. Before Westinghouse's innovation, train operators had to signal a team of brakemen to apply the brakes manually, carriage to carriage.

With his patent secure, Westinghouse established the Westinghouse Air Brake Company in 1869 and got to work manufacturing and improving the device. By 1905, the company produced over 1000 brakes per day to meet the enormous demand; at the time, over 2 million train cars and 89,000 locomotives had the Westinghouse Quick-Action Automatic Brake.

The success of Westinghouse's air brake and many other patents created a vast network of businesses worth up to $120 million at the turn of the 20th century. The financial crisis of 1907 devastated Westinghouse's business empire, but the inventor remained a wealthy man until his death on March 12, 1914. He left his country mansion, Solitude, to his son George, who died on November 18, 1933, leaving an estate worth $2,100,145, or $50,754,850.41 in 2024 dollars.

Tangle Teezer — Shaun Pulfrey

One doesn't have to be a titan of industry or an esteemed inventor to create a winning patent. Hair stylist Shaun Pulfrey patented the Tangle Teezer, the world's first detangling hairbrush, in over 30 countries, netting more than $89 million (70 million British pounds).

"I found many of my clients with long hair suffered with the same problem, it easily became tangled," Pulfrey explained in a case study published by the U.K. government, "I realised that tangles were a global problem, and that there wasn't anything on the market to deal with them." Consequently, Pulfrey designed a prototype that used "two-tiered teeth technology" to brush many different hair types without pulling.

He took his creation to "Dragons' Den" — a British business pitch show much like "Shark Tank" — and used a hirsute mannequin to demonstrate the marked difference between the Tangle Teezer and an ordinary hair brush. The "Dragons" were unimpressed, however, and dismissed Pulfrey with their customary rudeness.

It was their loss, though, for Pulfrey found investment elsewhere and turned Tangle Teezer into a multimillion-dollar venture popular with celebrities, influencers, and millions of customers. Pulfrey attributed some of his success to robust patenting, "We take a zero-tolerance approach to anyone breaching our IP. Having IP rights in so many countries makes trying to combat counterfeiters and patent infringements much easier."